Mohsin Hamid’s career as a writer has been remarkable and rather unique — he has a surprisingly slender portfolio of three rather short novels published over thirteen years, and yet he’s been able to have an outsize influence on contemporary world literature, routinely mentioned as one of the most important South Asian writers in English of the current generation.

Mohsin Hamid’s career as a writer has been remarkable and rather unique — he has a surprisingly slender portfolio of three rather short novels published over thirteen years, and yet he’s been able to have an outsize influence on contemporary world literature, routinely mentioned as one of the most important South Asian writers in English of the current generation.

Certainly, the fact that he is a sometimes diasporic Pakistani has been a great help in the sense that there are still so few Pakistani writers publishing in the West, taking on “big” themes such as terrorism, cosmopolitanism, or here, the impact of economic globalization on “rising Asia.” “Moth Smoke” (2000) broke new ground in showing us life in the youth subculture of Lahore, focusing on parties, sexuality, drugs, and yes, air conditioning — rather than the grim image of bombings, beheadings, and bismillahs that are usually the only reason Pakistan is ever mentioned in the western media. And of course his novel “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” (2007), whose Mira Nair-directed film adaptation just went into widespread release in the U.S., was an international best seller that has also become a key point of reference in discussions of the chilling impact of “9/11” around the world.

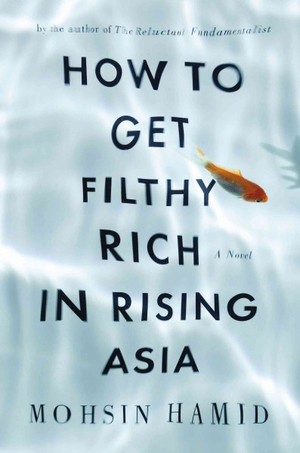

Both “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” and Hamid’s latest novel, “How To Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia” (which I’ll refer to as “Filthy Rich” from this point on) are books that aim to shock and provoke — beginning with their titles and continuing in the content of the prose. They are intended to be global conversation starters — and position themselves against the tradition of realist English-language novels of the Indian subcontinent, which aim to dutifully depict a particular society with a representative sampling of characters and voices associated with that society.

The intention to shock, as I say, begins with the titles of both books: I remember being a bit embarrassed to be a turbaned man on a plane reading “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” when it first came out (I ended up removing the dust jacket so as not to alarm other passengers). I had a somewhat different, but no less palpable, embarrassment reading “Filthy Rich” — again on a plane — on a recent trip to an academic conference in Toronto. What kind of person reads a book called “How To Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia”?

There are also certain rhetorical flourishes in “Filthy Rich,” where Hamid makes his distaste for the kind of “big,” tell-the-story-of-the-nation novel he wants to distance himself from:

It’s remarkable how many books fall into the category of self-help. Why, for example, do you persist in reading that much-praised, breathtakingly boring foreign novel, slogging through page after page after please-make-it-stop page of tar-slow prose and blush-inducing formal conceit, if not out of an impulse to understand distant lands that because of globalization are increasingly affecting life in your own? What is this impulse of yours, at its core, if not a desire for self-help?

By contrast to the “breathtakingly boring foreign novels” I frequently read and assign to my students (for I am the perfect reader for a paragraph like this), “Filthy Rich” flew by; I finished it in four hours, often entertained, though admittedly sometimes frustrated.

Some of the techniques that made “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” such a distinctive text are used in Hamid’s latest novel, “How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia.” The second person rhetorical address is again used, as is a sense of relative geographical and cultural abstraction. The country Pakistan is not named though it can be safely assumed, nor are the two main cities in Pakistan that feature in the novel, Lahore and Karachi — though they too are fairly easily recognizable. The protagonist also does not have a name, nor does his primary love interest (she is known throughout the novel as “pretty girl”), though both are given enough personal details to come alive as characters who emerge from lower middle class backgrounds in an unnamed small town in Pakistan, and then rise to become “filthy rich.”

“Filthy Rich” is an experiment in seeing how and whether a novelist can give as much attention to a rather bloodless economic plot as he does to his novel’s more conventional, character-based plot. The economic plot involves a young man who starts out as a DVD delivery boy, only to later get involved with bottled water distribution. He rises up through that industry at just the moment when the demand for bottled water is beginning to boom in “rising Asia,” and eventually becomes a corporate big-wig, making international deals relating to water supply, and becoming closely imbricated in the corrupt power structure of the unnamed-yet-recognizable government of Pakistan.

There is a brisk, clinical precision to the ways in which the protagonist’s business transformations are described in “Filthy Rich” that clearly benefit from the author’s own personal experiences in the corporate world (needless to say, these also figure in important ways in “The Reluctant Fundamentalist”). At times, it even seems to the reader as if that is where Hamid’s heart is — that is to say, in the fundamental heartlessness of a life oriented solely to business.

The more personal, romantic plot of “Filthy Rich” involves the unnamed protagonist’s relationship with a woman who identified as “the pretty girl” throughout the book. That romance is developed and then somewhat casually thrown aside after the first three chapters of “Filthy Rich” (chapter 3, in keeping with the “self-help” theme, is even entitled, “Don’t Fall in Love”). For much of the text, Hamid leaves the reader guessing as to whether his novel is really going to be as heartless as it initially appears as the protagonist enters into a loveless marriage with a business associate’s daughter — though at the end he resolves this question (and here I’m admittedly trying not to give too much away) in a way that this reader at least found satisfying.

Amardeep Singh teaches literature at Lehigh University. You can find him on Twitter or on his personal blog.