Malala Yousafzai may not have won the Nobel Peace Prize — presented in grand ceremony to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons last week — but the 16-year-old education activist and gunshot survivor has certainly won the hearts of Westerners and others across the globe. In fact, it’s hard not to feel affection and admiration for the outspoken, articulate, and intelligent Pakistani teenager whose brave advocacy for girls’ basic right to go to school so outraged Muslim extremists in her native Swat Valley that a Talib actually decided it was his duty to shoot her in the head in October 2012.

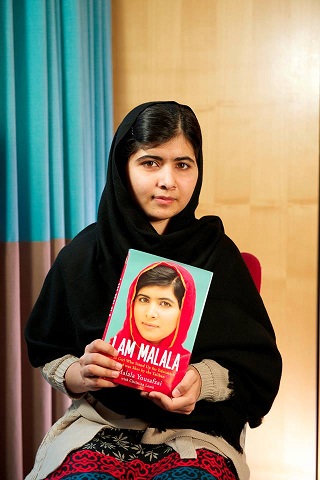

It’s really a shame that so many Pakistanis have this attitude toward Malala and her book. It’s as if anything the West loves, some Pakistanis must reflexively hate. Can’t we all love Malala and her message of peace? Yes, that sounds all kumbaya, but after reading I Am Malala, you’d have to have a heart of coal not to love this girl and endorse her message.

Here are the “Westernizing” subjects Malala was studying at her girls’ school in Swat Valley: math, physics, Urdu, English, Pashto, chemistry, biology, Islamiat, and Pakistan studies. Given that Asian high schoolers — not Western teens — crowd the top of international education rankings in reading, science, and math, learning these subjects will not turn the girls of Swat Valley into those of Sweet Valley High.

On 17 June 2004 an unmanned Predator dropped a Hellfire missile on Nek Mohammad in South Waziristan, apparently while he was giving an interview by satellite phone. He and the men around him were killed instantly. Local people had no idea what it was — back then we did not know that the Americans could do such a thing. Whatever you thought about Nek Mohammad, we were not at war with the Americans and were shocked that they would launch attacks from the sky on our soil. Across the tribal areas people were angry and many joined militant groups or formed lashkars, local militias.

The whole affair left a lot of bad feeling, particularly because on 17 March, the day after Davis was released, a drone attack on a tribal council in North Waziristan killed about forty people. The attack seemed to send the message that the CIA could do as it pleased in our country.

President Bush kept praising [then President Pervez] Musharraf, inviting him to Washington and calling him his buddy. My father and his friends were disgusted. They said the Americans always preferred dealing with dictators in Pakistan.

Anyone could see that Musharraf was double-dealing, taking American money while still helping the jihadis.… The Americans say they gave Pakistan billions of dollars to help their campaign against al-Qaeda, but we didn’t see a single cent. Musharraf built a mansion by Rawal Lake in Islamabad and bought an apartment in London. Every so often an important American official would complain that we weren’t doing enough and then suddenly some big fish would be caught.

We were warned not to be out late on Broad Street on weekend nights, as it could be dangerous. This made us laugh. How could it be unsafe compared to where we had come from? Were there Taliban beheading people? I didn’t tell my parents, but I flinched if an Asian-looking man came close.

Hopefully the trauma that triggered that flinching has diminished. Malala may not have won the Nobel Peace Prize, but she’s making wins for herself and girls around the world.