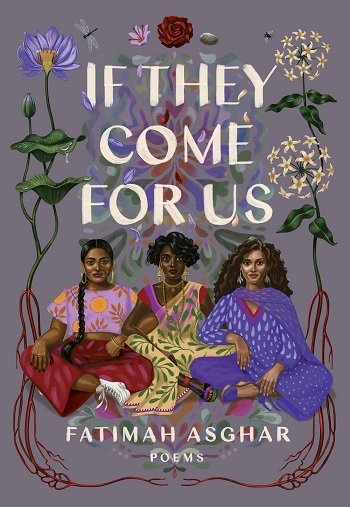

The dedication to Fatimah Asghar’s much-awaited poetry collection If They Come For Us reads, “my family, blood or not.” Over the course of the book, which spans the years since the Partition of Pakistan and India through our current age of Islamophobia and cultural hybridity, we revisit that very simple premise — who is the eponymous “Us”? Who is the “They”? Why must those delineations, those partitions, be made at all?

The speaker of these poems straddles separated spheres, identifying with one but claimed by another. That might come off as just this reviewer’s fancy way of an East versus West cliché, but this is a work less interested in political peacocking than it is in reclaiming the intimate, amidst the wash of history.

“This is a work less interested in political peacocking than it is in reclaiming the intimate, amidst the wash of history.”

The very first poem, “For Peshawar” after the 2014 Pakistan school attack, lays out many of the recurring themes that weave through the collection: the use of gold and red, the focus on the simple delights, the line breaks that fracture their enjoyment. “I wish them a mundane life,” Asghar reflects, imagining what could have been instead of what was:

Loneliness in a bookstore. Gold chapals.

Red kurtas. Walking home, sunat their backs. Searching the street

for a missing glove. Nothing glorious.A life. Alive. I Promise.

These external traumas are rendered personal through Asghar’s being, “not an over there but a memory lurking/in our blood, waiting to rise.” Her poems lace a vicious thread across times and places to show that the violence is not just cyclical, but often redundant, as continued in the following poem “Kal”, an ode to “where yesterday & tomorrow/are the same word. Kal.”

When reconnecting with the land, the fracture is made bare, such as the opening lines from “Ghareeb”:

on visits back your english sticks to everything.

your own aunties calls you ghareeb. strangerin your family’s house, you: runaway dog turned wild.

your little cousin pops gum & wears bras now: a stranger.black grass swaying in the field, glint of gold in her nose.

they say it so often, it must be your name, stranger.

Throughout the book are seven poems titled “Partition,” which signify the various borders: not only of time and place but also between the speaker’s self and body, her identity and the world that refuses to know it; between the blood kin she’s lost, and the family that has filled their gap.

“Throughout the book are seven poems titled ‘Partition,’ which signify the various borders…”

Asghar’s poetry is a space for these to live out in simultaneity, so that the present is given meaning and the past is given purpose, as shown in the second “Partition”:

freedom spat between every paan

-stained mouth as the colonizers leave1947: summer, in a Bihari marketplace

there’s nothing but sag & edible flowers.lines of people crowd the center

their hands: empty

—1993: summer, in New York City

I am four, sitting in a patch of grass

by Pathmarkan aunt teaches me how to tell

an edible flower

from a poisonous one

We see, the immigrant family trying to find ways to adapt their sense of home into the resources that America offers, like the sauce-less, cheese-less pizza crust used as naan in “Portrait of my Father, Alive,” (the loss of Asghar’s parents are a haunting spectre over the work) or a night out for an American dinner in “Old Country,” eerily echoing 1947:

& dyed his hair black every two weeks

so we couldn’t tell how old he was. We marched

single file towards the gigantic red lettering

across the gravel parking lot to announceour arrival…

The image of red trickles throughout, pooling in moments of celebration or commemoration, but always a stark reminder of how colonization shaped the poet’s life, like the fake rose petals that adorn Ullu’s eponymous “Gazebo”: “Always red. Always bright. Never in need of water.”

Or at a community cook out in the fourth “Partition”; the various diasporic foods at the same table — “A different spice here & there, maybe // a different name, maybe their bread thicker or our daal more red…”

Red is a signifier of “Us” — bound by the streams of blood shed over crossed borders, in those moments nudging dangerously close to a “melting pot” identity. It’s a conduit for who is welcome, and despite centering on several strong traumas, remains hopeful, tender, loving.

“Woven throughout are poems that peer inward, as Asghar explores another ‘Us,’ — the queer, the non-binary, genders who have no clear border.”

Woven throughout are poems that peer inward, as Asghar explores another “Us,” — the queer, the non-binary, genders who have no clear border. In “Boy,” the speaker literalizes the masculine inside her “…who grows my beard/& slaps my face when I wax” and then in “Other Body,” “with the boys in the park/& my mustache grew longer,” are strong images calling to the writer’s visible identities as a Muslim and woman, but continuing to queer the lines between the political to the personal. Amidst the confusion about what to think about these various kin, Asghar gives us a vibrant way of how to think about them.

So who is “They”? The domineering Western gaze, ever categorizing the hybridity, is explored in some experimental forms, such as “How We Left: Film Treatment,” written as a play-by-play process diary in making a television show or film; or “Microagression Bingo” show in the image of the classic gameboard, populated by daily stereotyped soundbytes and interactions; or the fifth “Partition,” in the form of an incomplete Mad-Libs. Re-mediating that gaze back through such inventive and playful ways is what makes this a success, giving power back to the oppressed.

In the end, the final poem “If They Come For Us” becomes an affirmation, a promise to stand by and follow those who are kin, through whatever lens, sung by a voice that’s at once woman, queer, brown, immigrant, American, youthful, and modern, weighted by history and bracing against the current Trump era, finding solace in between, even if, at the moment, it feels an arms reach too far.

* * *

Aditya Desai lives in Baltimore, currently teaching writing and revising a couple novels that he keeps threatening to finish someday. He received his MFA in Fiction from the University of Maryland, College Park. His stories, essays, and poems have appeared in B O D Y, The Rumpus, The Millions, The Margins, District Lit, The Kartika Review, CultureStrike, and others, which you can find most of at adityadesaiwriter.com. Find him on Twitter @atwittya.