Welcome back to The Aerogram Book Club, where Book Club editor Neelanjana Banerjee brings together writers and thinkers to discuss new South Asian books of significance every other month. Join in with your thoughts in the comments after reading the discussion between Banerjee and author Ali Eteraz.

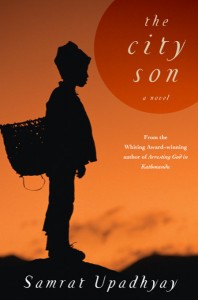

Samrat Upadhyay — the author of the story collections Arresting God in Kathmandu and The Royal Ghosts, and the novels The Guru of Love and Buddha’s Orphans — is the “first Nepali-born novelist writing in English to be published in the West,” and certainly the most well-known. He teaches in the Creative Writing MFA program at the University of Indiana in Bloomington.

Upadhyay’s latest novel, The City Son (Soho Press), begins when a scorned wife — living apart from her husband in the village — travels to Kathmandu when she learns her husband, a tutor, has taken another wife and had a son, named Tarun. Didi, the first wife, reclaims her husband, and expels his second family. As Tarun’s own mother begins to lose touch with reality, Didi begins a manipulative relationship with Tarun, which — as he gets older — turns from the emotional to the physical, threatening to destroy him.

Ali Eteraz: When I started reading this book it was without reading the book jacket or any of the publicity material. The only thing I glanced at was that the author was from Nepal and based in the United States. I immediately expected something akin to Kiran Desai’s Inheritance of Loss (maybe subconsciously because that book is set in an Indian region close to Nepal). But I really thought this book would be about immigrants and longing for the old home. Yet, there is literally none of that! I think I was relieved. There is nothing about coming to the West. The whole thing is set in Nepal.

Ali Eteraz: When I started reading this book it was without reading the book jacket or any of the publicity material. The only thing I glanced at was that the author was from Nepal and based in the United States. I immediately expected something akin to Kiran Desai’s Inheritance of Loss (maybe subconsciously because that book is set in an Indian region close to Nepal). But I really thought this book would be about immigrants and longing for the old home. Yet, there is literally none of that! I think I was relieved. There is nothing about coming to the West. The whole thing is set in Nepal.

I think by setting it all in one place and taking the globalization out of it, [pullquote align=”right”]The author relieves the rest of us of having to deal with any questions about exile or dislocated identities or post-colonialism[/pullquote]the author relieves the rest of us of having to deal with any questions about exile or dislocated identities or post-colonialism. We can then get to dealing with the questions of human motivations and human desires and that is what this book is about ultimately, isn’t it? Thus, the comparison this book evokes for me is more universalist; with books like Nabokov’s Lolita, or more recently, Alissa Nutting’s Tampa. Novels about unsympathetic characters. The only catch is that in the City Son the unsympathetic character, Didi, is not the protagonist (though I kind of wish she was).

Neelanjana Banerjee: Yes, Didi! Though the book focuses on Tarun, the innocent son of Masterji’s “second family” — whom he had with his beautiful former-student Apsara — Didi, Masterji’s first wife, is definitely the most fascinating. I don’t think I’ve encountered anyone quite like her in South Asian literature. The first physical description of her, when Masterji first goes to spy on her when he knows their marriage is to be arranged, is monstrous.

Neelanjana Banerjee: Yes, Didi! Though the book focuses on Tarun, the innocent son of Masterji’s “second family” — whom he had with his beautiful former-student Apsara — Didi, Masterji’s first wife, is definitely the most fascinating. I don’t think I’ve encountered anyone quite like her in South Asian literature. The first physical description of her, when Masterji first goes to spy on her when he knows their marriage is to be arranged, is monstrous.

She was round, her face like a soccer ball. It bhadda, flat and dark and uninteresting. Her cheeks were puffed up as though cotton had been stuffed inside. She had dark spots on her face.

Yet, once they marry, she is no blushing bride who lifts up her sari in the marriage bed. She “was a tigress who took immediate control.” Throughout the novel, Upadhyay maintains the contrast of Didi’s ugliness (and her provincialism) versus her sexual powers. At first, I was pleasantly surprised to hear about Didi’s sexual appetite, but her sexual vigor quickly turns into something equally as disgusting as her physical appearance.

In a way, Didi trades on this sexual power to control the actions of all of those around her: she pushes Apsara and Tarun out, and then slowly begins to control Tarun — first with motherly love (affection and food), and then with deeply disturbing manipulations — withholding her love, acting upset, until one day he comes to their house, and finds the two of them alone, and she begins to touch him inappropriately — which continues into his 20s.

But because most of the novel is in a third-person that stays close to Tarun, I didn’t quite understand Didi’s motivations. For only the first two chapters, does the narrator give us any insight into Didi. The morning after she finds out about her husband’s betrayal, the messenger asks her what Didi is thinking about and she says: “I can’t stop thinking about that beautiful boy.” So, did she know from the beginning that she was going to destroy this boy as an act of revenge? Later in the novel, her relationship to Tarun becomes more equal and she calls him her “labar”, a mispronounced version of “lover.”

Ali, you mentioned Tampa, and I was thinking a lot about that book — which I loved — because we so rarely get a portrait of a female pedophile or sexual deviant. But one of the reason’s I liked Tampa the most, was how that it [pullquote]We almost never get a portrait of female desire. This is especially true of South Asian literature.[/pullquote]made me realize that we almost never get a portrait of female desire. This is especially true of South Asian literature.

I felt like Tarun’s reactions — his trauma, his withdrawal from society, his inability to form relationships with women — are all accurate portrayals of someone who has been abused. But what exactly does the novel want us to think about Didi? Ali, you say you wish Didi was the protagonist, instead of the villain. Can you expand on that? In contrast to Didi, then Rukma — the woman Tarun’s marriage is eventually arranged to — could be seen as “the hero.” Did you see her this way?

Ali Eteraz: Neela! You’re putting me in this position where I feel like I will give away the meat of the book. I don’t review fiction a lot, and when I do, I try to treat it differently than when I review non-fiction. In non-fiction I drill down to the central ideas of the book and then jump out from there because I think that’s the purpose of a non-fiction work, more philosophical.

Ali Eteraz: Neela! You’re putting me in this position where I feel like I will give away the meat of the book. I don’t review fiction a lot, and when I do, I try to treat it differently than when I review non-fiction. In non-fiction I drill down to the central ideas of the book and then jump out from there because I think that’s the purpose of a non-fiction work, more philosophical.

But with fiction I am less inclined to do that, so you will find me to be more evasive in discussing characters and plots. I don’t want to kill the suspense for the reader, that thrill of entertainment when you know you’re approaching a complicating scene or a climactic moment.

With that said, let me talk about Didi some more, because you’re right, she is a compelling character. She isn’t some magical matriarch like you might get in Rushdie. She isn’t a saintly suffering striver like you might get in a Rohinton Mistry book. [pullquote align=”right”]She isn’t some magical matriarch like you might get in Rushdie. She isn’t a saintly suffering striver like you might get in a Rohinton Mistry book.[/pullquote]She’s much more single-minded about her pursuits and desires and that I think is what makes her compelling.

How did she become like this? What sustains her unilateralism? You suggested that it is her looks. That she is drawn to Tarun because she is unfortunately ugly and he is inherently beautiful and born to a beautiful woman. Does that mean that Didi is trying to channel his beauty into herself? Or is it more about punishing the beautiful? I think the reader will have to make up her own mind about that.

Speaking of Tarun, I guess we have to discuss him, because given the title of the book the novel is ostensibly about him. I actually felt him becoming more and more invisible in the book. This happens structurally within the narrative, too. You are getting much more information about Rukma, his wife, towards the end. I don’t know this author’s work well enough to say that this was done on purpose (I have to believe it was). But it sort of made me forget Tarun by the end, and I felt sad about that. It was like he had been erased.

The rise of Rukma, the heroic wife, in the narrative, for me, was unexpected. I am trying to figure out if I liked it. Part of me wanted that traditional feel-good story here, where Tarun kind of figures out what is happening and manages to overcome his situation, even heal himself in some supreme act of sovereignty.

On the other hand, his ability for autonomous action is completely shattered over the course of his life, so it is almost inevitable that someone else come in to confront Didi. That Rukma’s confrontation of Didi has its own selfish underpinnings made it more interesting for me, but not necessarily rewarding. Sometimes you just want an avenging savior. I hope that doesn’t sound moralistic.

Finally, I guess what I want to ask you is what you thought about the gender aspects here. The author is male, which we can kind of put aside, but in the book itself, even though the main character is male, the most dominant character is female, and the other males — Masterji, Mahesh Uncle (Tarun’s adopted father), the sons — are all pretty much either weak, intoxicated, or superfluous. What do you think was going on there?

Neelanjana Banerjee: You’re right, the men in this novel are mostly powerless — with both Tarun and his father, Masterji, portrayed as complete victims of Didi’s machinations. But Didi is portrayed with such little sympathy — in my reading — that I didn’t feel like it was a book that positively addressed the power of women.

Neelanjana Banerjee: You’re right, the men in this novel are mostly powerless — with both Tarun and his father, Masterji, portrayed as complete victims of Didi’s machinations. But Didi is portrayed with such little sympathy — in my reading — that I didn’t feel like it was a book that positively addressed the power of women.

Rukma, Tarun’s wife, seems to get the fairest treatment in the book. She is a modern woman of Nepal, who agrees to an arranged marriage after a love affair gone wrong. Little does she know that she is entering into an arrangement with a deeply wounded and traumatized man.

I appreciated what you say about Tarun disappearing throughout the novel. In a way, this is a great metaphor for [pullquote]The world is ready for a South Asian female Humbert Humbert to come to life on the page.[/pullquote]someone suffering from abuse — but for me, his disappearance was a consequence of the omiscent third-person narration. I am used to this kind of overarching third-person following characters throughout the novel, and felt disappointed that I lost the POVs that the book had gotten me interested in — namely that of Didi and Tarun.

I guess this proves that the world — or at least the two of us — are ready for a South Asian female Humbert Humbert to come to life on the page. I might have to call dibs on that one.

* * *

Ali Eteraz is the author of the forthcoming short story collection FALSIPEDIES & FIBSIENNES (Guernica Ed) and the 2014 winner of the 3 Quarks Daily Arts & Literature Prize judged by Mohsin Hamid. His memoir Children of Dust was published by HarperOne in 2011.

Neelanjana Banerjee’s arts journalism has appeared in Colorlines, Fiction Writers Review, HTML Giant, Hyphen, New America Media and more. She is the Managing Editor of Kaya Press, and an editor-at-large for the Los Angeles Review of Books. She teaches writing to young people and adults through artworxLA and Writing Workshops Los Angeles.