On February 6, 2015 in Madison, Alabama, Sureshbhai Patel, a 57-year-old Indian grandfather from Pij, Gujarat, was outside his son’s house when a neighbor called the police alleging that a “skinny Black man” was outside. When the police arrived, Patel, who speaks limited English, could not communicate with them, reportedly stating “No English, no English” repeatedly as he tried to point out his son’s home nearby. Madison police officer Eric Parker slammed him to the ground, and Mr. Patel was left partially paralyzed.

This past month, during the second trial of Officer Parker, the defense argued that Mr. Patel, whose primary language is Gujarati, has visited America several times and should understand and speak English. They blamed him for his own injuries, claiming that “Mr. Patel bears as much responsibility for this as anyone.”

As South Asian organizers invested in ending white supremacy, we see clear ties between anti-immigrant sentiment and Islamophobia, violence against South Asians, especially those of us with darker skin, and anti-Black racism. We brought this work home — asking ourselves and other South Asian organizers to initiate conversations with our families, to take a look at the different ways they understand how racism operates in this country. We wanted to explore how our lived experiences are tied to Black Lives Matter movements with our families. We are hoping that during this “holiday season,” other South Asians can talk to their families as well, and continue to bring these conversations into the often-fraught spaces of our homes, when safe and possible.

We asked South Asian organizers to talk to their mainly first-generation immigrant parents about the Sureshbhai Patel case and Black Lives Matter. Several themes emerged — South Asian racialization and experiences with police, the internalization of mainstream racism, and the ways that conversations about race and Black Lives Matter affect the relationships between immigrant parents and their kids. By no means are these stories wholly representative of our communities, nor do we think anything can fully capture the nuance and complexity of feeling. This is merely an extended snapshot of some of our families, intended to highlight some of the themes and challenges that come up when we talk about race.

The Participants: South Asian Organizers & Our Parents

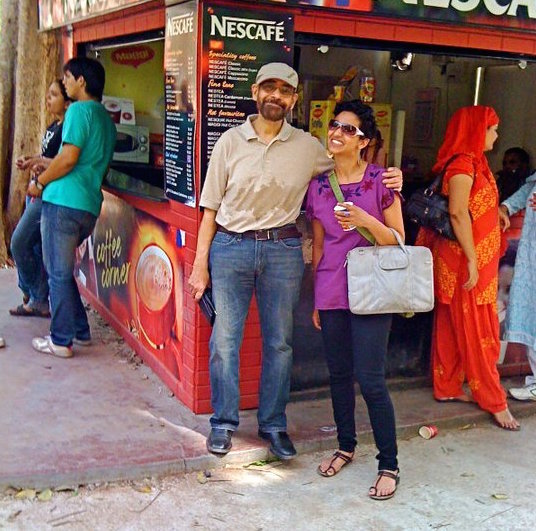

The brave and brilliant participants in this project are: Naaz Diwan and her parents; Alex and their parents; Vidushani and her ammi Vinitha; Alina Bee and her baba Jahanzaib Usmani; and Anjali and her parents Hema and Srini. Some of these names are pseudonyms; others are not used at all. We know that these conversations are hard and participants vulnerable, and respected wishes to participate anonymously if anyone so desired.

Our participants are from a range of ethnicities connected to three different South Asian countries — Sri Lanka, Pakistan and India — and a range of religious backgrounds, including Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam. The organizers and their families included hetero, queer, cis, trans, and gender non-conforming people. They live across multiple states and regions here in the U.S., including California, the DC/DMV area, Wisconsin, Alabama, and Ohio.

We also acknowledge that we are all non-Black South Asians talking to parents who identify as middle to upper-middle class. These experiences can be radically different when speaking with people of mixed racial heritage, Indo-Caribbean people, and South Asians living in working-class communities here in the U.S. That said, as middle and upper-middle class South Asians, this is our work, and we are committed to doing it.

Police & Policing

The South Asian parents who were interviewed for this project grappled with a complicated relationship to policing and the state. They talked about being racialized through profiling, policing and tactics that made them afraid, but they also maintained faith in the police. As organizers, we understood this tension as a product of their status as English-proficient immigrants of color who are not Black as well as their middle to upper middle class status. The issue of English language access as a means of avoiding police violence came up repeatedly.

After talking about the experience of Sureshbhai Patel, Naaz’s father and Vidushani’s ammi, Vinitha, both shared stories of fear, weaving connections between the experiences of South Asian and Black people in the U.S. “Police aren’t actually after Indian people but Black people,” Naaz’s father, a Muslim man raised in Bombay, explained. “And when they perceive someone as Black, they go after them.” He described being shocked by the Patel attack. “I thought ‘Oh my God, his skin color must have been dark…first thing I thought was if he was White this would not have happened.”

“Police aren’t actually after Indian people but Black people and when they perceive someone as Black they go after them.” — Naaz’s father

“Police aren’t actually after Indian people but Black people and when they perceive someone as Black they go after them.” — Naaz’s father

Naaz’s father then described an encounter that illustrates the ripple effects of anti-Black racism. He told of the experience of a family friend that had close parallels to the Patel incident: “In [the] 1980s…one day, he was walking and someone called and said there is a Black guy walking in the neighborhood. So then the police came. He was doing nothing. Luckily he spoke English so he could explain his son is a doctor and lives here.”

Vinitha is from Weligama, Sri Lanka, a small fishing town that has become a center of tourism. She echoed this sentiment, describing the fears of South Asian people who are non-English speaking immigrants and the ways that immigrant communities are policed. She talked about her co-worker, saying “her parents are Indian and they come to visit once a year, they can’t speak English and have a heavy accent…There is no freedom to leave the house, they are scared. This freedom is fake.”

Taken together with the assault on Sureshbhai Patel, these two anecdotes highlighted to us the fear of police as darker-skinned people, and the crucial role of speaking English for South Asian migrants as a means of avoiding violence by the police in the United States.

In several of the interviews, South Asian parents simultaneously claimed to not have any problems with the police, and then went on to describe “racist” incidents or racially based fears. Naaz’s mother, also from Bombay, opened a story about getting pulled over by a racist police officer with the line “I never had any problem either but…” She then went on to relate, “one time when I was driving in the morning at 6:30 a.m….two police, not one…stopped me and I said, ‘What?’ and they said ‘You’re drunk’ and they made me get out and walk. And they still gave me a ticket. I wasn’t drunk, I was going to work. He was kind of racist. I explained to him I was going to work and you can smell my breath.”

“I wouldn’t get justice in the White-run court.” — Vinitha, Vidushani’s ammi

Alex’s parents, also from Sri Lanka, echoed this contradiction. Alex’s mother said: “I don’t feel in the slightest bit nervous with cops. It’s because we’ve known some cops and never had that experience ourselves, so that’s why we don’t feel nervous at all about it. But I can see families where their parents don’t speak English, they might be nervous, thinking it might happen to their family. But personally for us, I didn’t even think about it in that way at all.”

Alex asked their mother about a previous conversation they’d had about whether or not she feared for her darker-skinned South Asian son after hearing about Mike Brown’s murder. “I remember this conversation,” she replied. “Up until that time, I hadn’t really thought about it…After we had that conversation, I do think about it a bit. Honestly, I just pray for you guys.”

Alex’s mother maintains a trust in police and policing, even while acknowledging her own fear for her family. In describing being consistently profiled at the airport in the decade after the September 11th attacks, she said, “You can’t blame them. After 9/11 everybody was on edge. It’s safer for all of us to make sure they check these people. Now you get prescreened and sometimes avoid security — it works both ways. I honestly don’t look at it in a racially motivated way at all. Let them check – who cares? I have nothing to hide.”

Though her parents are now active in local Black Lives Matter work, Anjali expressed surprise that she “couldn’t get [her father] to say much about the Sureshbhai Patel case — odd, since I live in Madison, Alabama — except that things like this just didn’t happen 35 years ago. Attacks by racists, sure, but not by the police.”

This tension between fear of police as darker-skinned people in the U.S. and trust in police as an institution was a repeated theme. Many participants located the violence of policing in individual rogue cops, and not as a systemic issue. Surprisingly, few of the South Asian parents we interviewed drew connections between anti-Black racism and Islamophobia.

We need to do more work to connect Black and brown experiences of race, profiling, and state violence as systemic issues, instead of understanding our experiences of policing and profiling as individual and isolated events. In contradiction to the analysis touted by the Hindu American Foundation, we also note that none of the parents interviewed, including those that identify as Hindu, believed that “Hinduphobia” was a factor in police violence against South Asians, which resonates with our own understanding of the issue.

Complicity & Internalized Racism

Some of the parents that were interviewed for this project expressed ideas that reflected the American internalization of anti-Black racism. These ranged from denying the reality of Black people’s experiences of police violence to justifying the selective targeting of Black people.

Some parents contrasted South Asian and Black communities, explaining police violence against Black people by appeals to stereotypes about the two groups. South Asians were described as “non violent” by Naaz Diwan’s parents, while words like “drug dealers” and “broken families” were used by Alex’s parents to characterize Black people. These stereotypes have a history that goes back decades and have frequently been used in the United States to blame Black people for the racism, and racist police violence, they face, while holding up South Asians as a model minority.

Alex’s Colombo-raised father said that the murder of Ferguson police violence victim Mike Brown “was entirely his fault. He didn’t do what the cop told him. You have to look at it both ways. You look at [it] as a Black and White problem. The cops have to take care of themselves too.” Naaz’s mother, too, implied that Sureshbhai’s attacker was tried while Black victims receive miniscule accountability because Sureshbhai’s family went “to the right people to get justice,” implying that Black victims’ families do not.

These comments affirmed our belief that the tendency to hold Black people and communities responsible for the racism and violence they experience by police and other institutions is an issue in South Asian communities in the United States. Others, however, expressed greater sensitivity to race issues affecting Black Americans, contrary to stereotypes about first generation immigrants.

Vinitha said, “Police need more common sense — White folks need common sense. They need patience and they are so arrogant.” Anjali’s appa, Srini, said of his grad school experience in Newark in the early 1980s, “when we were young, it was very difficult not to turn into an anti-Black racist, because if you were a pathetic, weak Indian kid you’d be mugged….It was a scary place.” In part due to his relationship with his children, he has now become a racial justice activist in Milwaukee, far from Tamil Nadu, India or Kuwait, the two places he spent his childhood.

Relationship Between Kids & Parents

These conversations didn’t just bring out political tensions; they also shone a light on the relationships between organizers and their immigrant parents.

Some parents took pride in the ways their kids were fighting for a better world. As Naaz’s father said, “I wish more people were like you and get involved. It’s a very positive thing to do. Not just for Black people, but people of all dark skin. The more dialogue we have, the better relations we’ll have…that’s what I think.”

For others, pride was mixed with fear. This may be because many South Asians come from countries with recent histories of political turmoil and state violence, and the fear of backlash from political work is ever present.

Vinitha said, “I’m happy. At least someone is doing something. At the same time I’m scared. I’m not sure what kind of threats you will get. You have to be careful.” Alex’s mom, from Colombo, Sri Lanka, shared these fears. “With you, the biggest problem I have is your safety. That is the biggest problem I have, which is why I pray for your safety.”

Other parents expressed a sense of cynicism. Jahanzaib, Alina’s Karachi-raised father, asked, “You understand the world is horrible and people are looking out for themselves only and it’s easier for some people. But that’s life. You think you’re going to sway anyone with feelings or convince them to give up their power? Why would people do that?”

When Alina pushed back, highlighting ways that people have been organizing and movements in history, he replied, “It’s debilitating to keep thinking about all the horrible things happening in the world. That’s why I just prefer to make money and then I can help that way. I can’t help if I don’t help myself first.”

The feeling of being powerless in the face of systemic racism and injustice was a repeated theme. Despite feeling sympathetic and understanding institutional racism, the resignation of having to make ends meet and survive meant that there was cap to how much empathy and resistance people exercised.

“Your generation is actually far more conscious, and you have a huge window to change your parents’ generation, and you should be encouraged to do so.” — Srini, Anjali’s appa

Anjali’s parents credited her and her brother with pushing their own activism. Her appa, Srini, said, “It’s been a mutually-reinforcing relationship…we were probably getting there on our own, but your personal growth has influenced and amplified our personal beliefs.” Anjali added, “My brother, Mohan, probably gave them the push they needed to really go out and get involved with the Milwaukee Coalition for Justice and ACLU.” Her parents said, “Every kid who has that consciousness but understands that their parents may not, has an opportunity to change that. And it may not work, but then maybe the next generation will be better.”

This last reflection on the mutual process of generations of South Asians shaping each others’ political activism left us with hope.

Reflections On The Process

Before leaving the subject, we want to present some reflections from our participants who were courageous enough to have potentially fraught conversations with their parents about a sensitive issue.

We were somewhat surprised and humbled that all of them appeared to have had positive, if messy, experiences in talking about anti-Black racism and the Sureshbhai Patel assault with their parents. This outcome and our own sentiments in reading the responses of participants reinforced our sense that, in many cases, the bonds within South Asian immigrant families can withstand the difficulties posed by a subject as sensitive as race relations and anti-Black racism in the United States.

Vidushani said she was surprised that the conversation was “easier than expected”. She described how she and her mother were both “really nervous; but when we started talking things just clicked…she was really receptive to having a conversation and connecting it to her own experience.”

Anjali, whose parents are racial justice activists, recognized that the “conversation was a lot easier to have in my family than in many others” but noted that the experienced prompted her entire family to sit down and have a focused discussion about the issue.

Naaz said, “I really enjoyed this experience. It was so incredible to see how their perspectives have evolved since my childhood and since the rise of Black Lives Matter activism.” Alex, whose parents offered a sharp contrast at points with their own beliefs, said, “The project opened the space for us to have this conversation in a way that was less loaded, and allowed us to go deeper into this conversation without as many emotions.”

Of course, the conversations were not entirely smooth sailing for most of the participants.

Alex, for example, said that “it was incredibly hard to hear my parents express views that differed so strongly from mine, and that reflect the racism so present in our news media.” Similarly, Naaz said, “When I heard my parents say that black folks are more violent than Indians I grimaced and clenched and waited. The characterization of Indians as non-violent and blacks as involved with robberies was difficult to stomach.” Alina, too, who enjoyed the vigorous debate with her father, nonetheless maintained that “it has to be very contained and focused” in order to avoid dismissiveness towards the conversation or defensiveness around recognizing his complicity in certain things.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Reading these interviews — and for some of us, interviewing our own families — was at points difficult, and messy. Yet, these conversations opened up space that we need in our middle to upper middle class South Asian families.

If we’re going to build an understanding of solidarity, oppression and liberation that includes our families, we need to start at home — when that is safe and possible. These conversations can be painful, but they are necessary and, based on our participants’ responses, a solid tool for extending our love.

We’re sharing this now to reveal some of the internal conversations in our community, but also to inspire more of these discussions, especially as we approach the “holiday season.” We’re still collecting interviews of South Asians and their family members talking about race, police brutality, and Black Lives Matter. If you’re interested in having a conversation, submitting a transcript and/or a picture, or if you need support to get started, email API Resistance at apiresistance@gmail.com.

For more resources on confronting anti-Blackness in our South Asian communities, check out:

Queer South Asian National Network Curriculum Guide: “It Starts at Home: Confronting Anti-Blackness in South Asian Communities”

Anirvan Chatterjee: “The Secret History of South Asian and African American Solidarity”

To Speak A Song: The Revolution Starts with my Thathi: Strategies for South Asians to bring #BlackLivesMatter Home

Seeding Change: Asian American Solidarity Statements and Articles in Support of #BlackLivesMatter

* * *

API Resistance is a solidarity group of Asian Pacific Islanders (APIs) that formed to support Black Lives Matter organizing in the D.C. area. API Resistance chooses resistance against oppression. We stand for Black liberation & liberation of all oppressed people.

Is it so hard to believe that a person of color trusts the police?

Activists create a narrative of how the world works, and when faced with people whose life experiences run counter to that narrative, they chalk it up to people not understanding how the world works. Why are their views dismissed as invalid?

My husband and I are professionals, not just 2 old timers living with children as immigrants, we have even donated several acres of land in Howard county to develop houses for domestic violence victims etc . We were stopped by a police man one evening when we were returning from Good friday evening prayers, the police man followed us few yards and stopped us near a cemetery on st Johns lane, asked my husband to get out of the care, shouted at me to stay in the care, it was dark, I was scared , so I called the police dept and they said the the urgent in charge is on the road[ the guy who stopped us was the one in charge] . I told the guy who answered the phone that I am afraid and that my husband is thrown against the car and frisked with absolutely no reason given. when the second patrol car arrived, they talked and gave us a ticket saying that we crossed a white line far away from where we were stopped.

I complained top the head of howard county police dept, complained to the HC Executive . the Executive was Mr Roby who deputized his administrative asst to look into it Nothing was done about it.

We had gone to the court for the ticket. the policeman was there. The judge said ” My husband should be given a medal for passing through that horrible site and not a ticket” Judge dismissed the case.

so this is the Howard county Police department

We had been faithfully giving contribution for all kinds of police collection and things. Since then if I answer the phone I don’t pledge any su[pport.