Originally released as a BBC Radio 4 podcast series, Incarnations is now out as a book which contains 50 short biographies by historian Sunil Khilnani spanning the past 2500 years, helping to recapture the human dimension of how the world’s largest democracy came to be. Incarnations: A History of India in Fifty Lives, is an introduction to India and a reinterpretation of its history. In rocket launches and ayurvedic call centers, in slum temples and Bollywood studios, in California communes and grimy ports, Khilnani examines the continued, and often surprising, relevance of the men and women who have made India — and the world — what it is.

Originally released as a BBC Radio 4 podcast series, Incarnations is now out as a book which contains 50 short biographies by historian Sunil Khilnani spanning the past 2500 years, helping to recapture the human dimension of how the world’s largest democracy came to be. Incarnations: A History of India in Fifty Lives, is an introduction to India and a reinterpretation of its history. In rocket launches and ayurvedic call centers, in slum temples and Bollywood studios, in California communes and grimy ports, Khilnani examines the continued, and often surprising, relevance of the men and women who have made India — and the world — what it is.

The author completes his stateside book tour for Incarnations with upcoming dates October 23 at The Getty Center in Los Angeles and October 24 at Stanford University. Read an excerpt from his writing on Malik Ambar, who began life as a 17th-century Ethiopian slave and rose to become the nemesis of the Mughal Empire, forcing India to confront its bias against Africans. (c) 2016, Sunil Khilnani. Reprinted with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

* * *

Years ago, I managed to get tickets to the first cricket Test match to be played in the city of Ahmedabad in Gujarat. Opposing the Indian team was a West Indian eleven that included the peerless Viv Richards. The excitement as the crowds streamed to the new test ground was manic, joyful, but I left the match remembering neither the score nor individual performances. The reactions of the Ahmedabad spectators, though, I won’t forget. As the West Indians took to the field, loud monkey whoops filled the air, and bananas came raining down from the stands. The pelted players, probably the greatest West Indian team in history, stood there in their flannels, stunned.

Indians’ particular contempt for people of African descent — a racism shared even by Mohandas Gandhi, as evident in his South African years — doesn’t get talked about much, which is surely one reason little has changed in the thirty-odd years since I watched that troubling match. It’s telling that a word still widely used in Hindi to refer to black Africans is habshi — shorthand in common usage for a dark-skinned slave.

The word habshi, derived from Arabic and Persian terms for an Abyssinian, has a long history in India, one that’s not often remembered today in the nation, or beyond. The standard image of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century slavery is of ships moving west from Africa, their shackled human cargo destined to feed the New World’s demand for mass labor on cotton and tobacco plantations. Yet the slave economy was a genuinely global one, stretching from Africa to East Asia. Slaves were also sent eastward across the Indian Ocean, to bolster the public and private militias of the Deccan Plateau of southern India.

One of these slaves, whose story is rarely told, rose to become a power broker, even a kingmaker, in the Deccan. A persistent tormentor and nemesis of the vast Mughal Empire to the north, he helped set the contours of power in the subcontinent in the century before the dawn of the colonial era. His name was Malik Ambar.

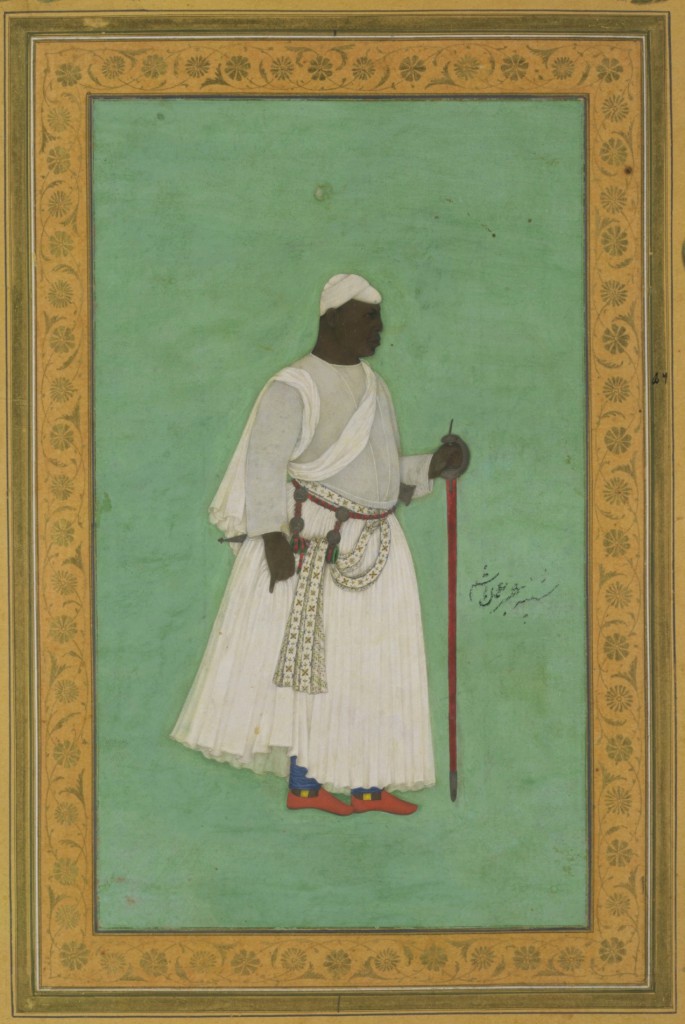

In an early, unsettling seventeenth-century miniature painting of Malik Ambar, his severed head is impaled on a spear. A short distance away, a Mughal archer, balanced on a globe and dressed in a wine-colored robe, jeweled belt, and white slippers, takes careful aim at the African’s face. To Richard Eaton, a professor at the University of Arizona and a scholar of Deccan history, “it’s a remarkable painting filled with symbolism. Around Malik Ambar you have owls — live owls and dead owls — associating him with darkness and rebellion.”

Malik Ambar was born in the mid-1500s. His given name was Chapu. He was probably a pagan, and he was sold into slavery — possibly by his own impoverished parents — while very young. The interests that conspired to send the boy born Chapu to India were rooted in trade, a story that also has cotton at its heart. The flow of slaves “was driven largely by the demand for Indian textiles on the part of the Ethiopian kingdom,” Richard Eaton explains, “so on one side — the western, African side — you have demand for Indian textiles. And on the eastern side you have an equal demand for military slavery.”

The trade in African slave warriors flourished in places riven by political instability, places with enmities between, and within, clans—places, in other words, much like the sixteenth-century Deccan. The Deccan Plateau covers much of central southern India, and with its western ports and rich hinterlands, it was a global crossroads. With the flow of incomers came native resentments. But the habshis were detached both from their own families and from the tangled knots of local alliances and feuds. That estrangement made them valuable tools to their masters. Recognizing that they would never return home to Africa, they had little choice but to throw in their lot with their owners.

Malik Ambar’s journey from Abyssinia to the Deccan was a meandering one. When first enslaved, he was sent to Baghdad, where he was converted to Islam and renamed. He was manifestly clever, and his first owner taught him finance and administration, in Arabic, a practice of education not uncommon in the warrior-slave trade. African slaves were valued not just for their strength, but also for their leadership abilities, strategic intelligence, and cultural flexibility.

When his first master died, Malik Ambar was sold again, perhaps repeatedly. At some point during his West Asian sojourn, he picked up Iranian irrigation techniques. We actually have a contemporary Dutch record of one transaction in which Malik Ambar was sold for an impressive price of eighty guilders, a twisted tribute to his exceptional capabilities. Then, perhaps late in his teens, he ended up with many compatriots in an Arab dhow, plowing southeast across the Arabian Sea toward the Konkan coast, in today’s Maharashtra. He had acquired by now a cultural education to rival that of his future owners.

Malik Ambar’s new Indian master was Chengiz Khan, peshwa, or “chief minister,” of the Deccan’s fading Nizam Shahi sultanate. Chengiz was known to give his habshis room for advancement—for he was himself a habshi and a former slave. Malik Ambar made it his business to watch Chengiz closely as he managed his role as peshwa. Eventually, the slave who already had financial management and engineering skills began absorbing political strategy from his master, who would prove to be his last.

○

Malik Ambar’s story complicates our assumptions about slavery, particularly the view that all slaves were cut off from the avenues of social mobility enjoyed by free men. The reason he would, over time, be able to mimic his master and rise from slave to kingmaker had to do not just with his own abilities, but also with the military slavery system that dated back to the Arab world of the tenth century. When not on the battlefield, these elite slaves were often appointed to trusted roles within the household: bodyguards, valets, and guardians of the harem. They were educated and nurtured by their masters, treated almost like sons—in exchange for their total loyalty, of course. And when their masters died, they were often freed.

Some of these educated, capable freed slaves became freelancers and mercenaries, and a few maneuvered themselves into positions of genuine power, as Malik Ambar’s own master had done. When Chengiz Khan died in 1575, Malik Ambar was still in his midtwenties. He was smart, ambitious, charismatic, highly skilled — and now free.

As a mercenary serving a series of local commanders, Malik Ambar spent the next two decades building a band of loyal soldiers of his own—many of them, ironically, Ethiopian habshis engaged by him on the usual slave terms. Having seen what Chengiz Khan achieved, Malik Ambar wanted to go farther, and succeeded in part by lucky timing. By 1595 he had built a large army at a crucial moment in Deccan history. The sultan he was employed by needed him desperately, for the Mughal Empire, expanding by the day under the strategic brilliance of Akbar, was knocking on the door.

Akbar’s forces had been edging steadily southward, seeking to capture Maratha territory and subdue the rulers of the Deccan. They laid siege to the fortified city of Ahmednagar, the politically fractious capital of the Nizam Shahi sultanate. But in a daring nighttime maneuver, Malik Ambar and his troops managed to break out of the city and escape through the enemy lines. While the city fell, many of the cavalrymen of the defeated ruler joined Malik Ambar. He could now command a mixed group of around seven thousand crack fighters. For the next three decades, successive Mughal emperors would send their forces to try to control the Deccan countryside. Against Malik Ambar, they would fail.

* * *

* * *

Sunil Khilnani, born in New Delhi and educated at Cambridge University, teaches politics at Birkbeck College, University of London. The author of Arguing Revolution, he is at work on a biography of Nehru.