Lahore native Kamil Ahsan moved to Chicago for graduate school in 2012. A freelance journalist, Ahsan holds a Ph.D. in developmental biology, a master’s degree in history of science, is an assistant literary magazine editor at Barrelhouse Magazine, and a freelance book critic. This fall, he will begin a Ph.D. in history at Yale University. If there’s anything one can glean from such a varied resume, it is that Ahsan has always sought connections between seemingly disparate people, places, and narratives.

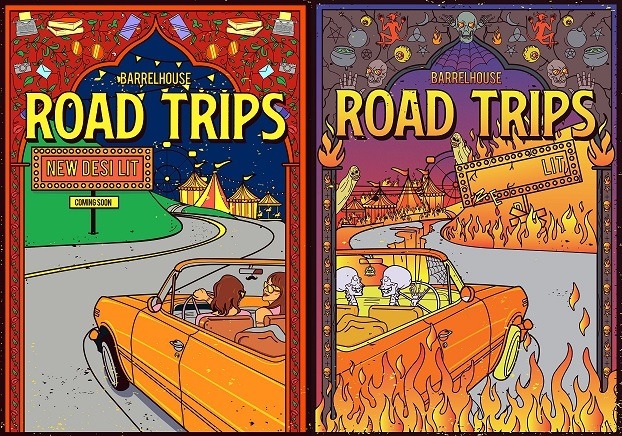

This curiosity has spawned Barrelhouse Magazine’s Desi issue, “Road Trips,” where Ahsan has assembled twelve indelible short stories (including one novel excerpt), artwork, and interviews with South Asian writers (Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, Kashmiri, Indian, and Pakistani) from South Asia and of the diaspora. Interspersed throughout the issue are conversations between the writers, where, among other things, they discuss the fraught term, desi.

The stories span a wide range of genres, including post-apocalyptic, political, contemporary, speculative, humorous, and erotic, and each story is paired with an original piece of artwork, the result of a collaboration between the writer and the artist.

The issue will go live, online, on June 10.

I spoke with Ahsan on the phone about his vision for the issue, and his quest to understand the meaning and the movement of South Asian literature.

***

Anjali Enjeti: You call this the desi issue. What does the word “desi” mean to you as the editor, and how did the writers interpret it?

Kamil Ahsan: What is desi, what that means, is not settled, and the use of the term for this issue is almost tongue-in-cheek. Until recently, I never would have guessed that it was a controversial term. Many writers don’t identify with the term, because they feel generally it refers to only parts of the subcontinent, or does not refer to people who grew up in the U.S. But I always thought of it as a beautiful word like Latinx, that traverses state lines and describes all of us no matter who we are. I tend to agree with the opinion of the writer Vijay Prashad, who said this in an interview:

I love the word ‘desi.’ It is so beautiful. I can go around saying it over and over again. I’m of the view that it is the best word to describe ourselves. Phrases like African American, Asian American, Hispanic American, etc. are bureaucratic words that do not hold within them the revolutionary aspirations and histories of a people (categorized but not controlled). I prefer words like Black, desi, Latino, Chicano, because these words raise associations of struggles, such as the Black Power movement (‘Black is Beautiful,’ etc.), the Chicano struggles of the farm workers, of La Raza, and what not. Desi seems to be a similar word, one filled with so much historical emotion. And again, it is an ironic word, because it means of the homeland, but it does not say what that homeland is. We who use it do not hearken back to the ‘homeland’ of the subcontinent, because we are generally not nationalistic in that sense. Our homeland is an imaginary one that stretches from Jackson Heights to the Ghadar Party, from the rallies against Dotbusters to the Komagata Maru, from the 1965 Immigration Act to Devon Street.

My impression is that “desi” has been used in very exclusionary ways in the U.S., and this disjuncture makes complete sense. This is something I wanted to dig into, question, and interrogate for the issue.

AE: How did you get the idea for the issue?

KA: I recently read the English translation of Qurratulain Hyder’s Urdu novel, Aag Ka Darya, or River of Fire. She wrote the novel and then translated it herself before she passed away in 2007. I had never heard about this book, never encountered it in a bookstore, and it never came up in college, but it’s an overdue history of the Indian subcontinent. Every depiction is of a Hindu-Muslim mixture of cultures, cultures that will never be separated from each other. She did not depict Indians and Pakistanis as the state would have liked.

Hyder’s novel crystallizes the fact that we have a tradition. Maybe use of the term “desi” is not the best way to characterize this, but this tradition is something we can lay claim to. All of us can co-exist in the same space. This Barrelhouse issue is about a people.

AE: Why is it important to seek work free of South Asian stereotypes?

KA: It’s critical and important because not only are there huge generational differences in how South Asians perceive themselves, but there are huge differences in how South Asians from different geographic regions perceive themselves. We must know what these narratives are and understand what our responsibility is to these narratives.

Also, I didn’t want the writers in this issue to have to worry about their audience. I wanted it to feel authentic to us.

AE: How did you find the writers you solicited?

KA: I read about a hundred stories by South Asian writers in bookstores and wrote a list of names. I was very shocked, as the list I eventually compiled was made up of writers I’d never heard of before. (Initially, I thought I would solicit bigger, well known writers.)

When I solicited the writers, I did say, this is what I read of yours, this is what I find intriguing. Once they said yes, I told them that I wanted them to push their writing as far as they possibly could, to do whatever they thought was extreme and out of the box.

AE: Which is interesting, because, ultimately, the issue feels very cohesive to me. The stories fit together very well.

KA: That’s pleasantly surprising to hear. That wasn’t my intention. I do believe that this issue was more than just putting South Asian stories in one place. I wanted a diversity of narrative and tradition. I received stories that weren’t anything like what I had in mind, like Abeer Hoque’s erotic travel story, “Fuck-All Gall.” It’s amazing. That story upended my expectations for what I thought I’d see in the issue.

Nur Nasreen Ibrahim writes speculative fiction about climate. Her story “The Death of a Glacier,” is a reporter’s dispatch from a village next to a melting glacier in the northern Himalayas. One would think she was a glaciologist. It’s so different than anything she’s even written.

AE: One of the things I loved about these stories — is that they all ended with more questions than answers. There is no compulsion to wrap the endings up neatly.

KA: I was pushing the writers to give me their most risky and most edgy work. There’s not a lot of high falutin stuff — the stories are just beautifully authentic. Sarah Thankam Mathews’ “The Storms” for example, nails the desi parent-child dynamic. The interaction between the mother and the daughter, that push and pull, is so familiar.

Tara Isabel Zambrano, who wrote “Alligators,” is a flash fiction writer. Her first version of the story, about a daughter traveling with the ashes of her mother, who died from suicide, started out quite a bit shorter than final version. We started asking questions — and once we asked enough questions, she had a whole new story.

“The Installation” by Ahsan Butt, a story about a place where one can experience the first moments of their death, is part of a larger project. The story is fantasy or speculative but really it’s philosophical.

AE: Or even religious.

KA: Yes, it’s hard to pin down! There’s a sort of Sufi slant to it.

AE: And these stories are decolonized — there’s no deference to the white or American perspective or experience.

KA: Interesting that you put it that way — decolonized. My criticism of some of the fiction from big name South Asian authors, such as Mohsin Hamid and Arundhati Roy, is that sometimes their novels, and the stories they tell reflect a different kind of orientalism in that they feel the need to hit so many hot button issues at once, like turmoil in Kashmir and refugee camps.

Many people in South Asia are living perfectly normal lives. Where are those stories?

Feroz Rather’s “A Strange Call from the Mountain,” about a lorry driver — reflects a different kind of normalcy. Rather grew up in Indian-occupied Kashmir. How do you live in the world’s biggest open-air prison and create art? How do you wring out beauty out of brutality? Rather’s story is very spiritual — but there is so much violence hiding behind those words. I can’t describe what this story meant to me.

AE: What this also points to is the difference in how South Asian natives perceive South Asian literature, verses how South Asians in the diaspora perceive it.

KA: I met the author Chaya Bhuvaneswar at the Association for Writers and Writing Programs conference in Portland recently — she also has a story in the desi issue. We discussed some of the most popular books that have come out of South Asia. She loved some that felt like a trope to me. This is because we grew up in two different literary landscapes, so our perceptions of South Asian literature are very different.

There’s nothing wrong with this — I want to give space for this difference to breathe, to hold space where we learn about one another. I don’t want it resolved in the desi issue. We may disagree with each other’s viewpoint, but it’s fair to have a different viewpoint.

The context is key. It begs the question, what are we looking for and where are we going with South Asian literature?

***

Anjali Enjeti is an award-winning essayist, journalist and critic based in Atlanta. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, Newsday, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Nation, and elsewhere. Her collection of essays about identity is forthcoming from the University of Georgia Press. She currently serves as Vice President of Membership for the National Book Critics Circle and teaches creative nonfiction in the MFA program at Reinhardt University.