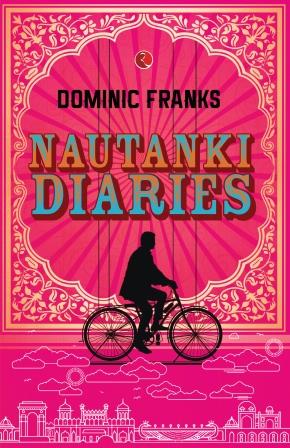

Nautanki Diaries

By Dominic Franks

Rupa Publications (Feb. 2018)

272 Pages

***

When 30-year-old Dominic Franks decided to do a cross-country bicycle ride from Bengaluru to Delhi, just in time for the 2010 Commonwealth Games’ opening ceremony, he knew that covering six states in 22 days over a 2100-2200 kilometer stretch would be a tough physical journey. A sports coach and mentor from his high school days, Shikaari, had already covered this ground in 1982, when road conditions and amenities had been much worse.

What Franks was probably not quite so prepared for was the inner journey — emotionally and intellectually — he would also end up taking. Whether sticking to his well-planned highway routes or suddenly wandering down little side-roads to unknown towns and villages, Franks and the documentary film crew accompanying him met and spent time with interesting and diverse characters. Not only did these encounters frequently jolt him off of his single-mindedness of getting from Point A to Point B, they also made him pause and ponder on the complexities and complications of simply making it from one day to the next.

Over the last two or three decades, cross-country bicycling adventures have become quite the thing, especially across the U.S. and Europe. For the most part, those who take them on are trying to cope with some personal tragedy, navigating through a midlife crisis, or simply embracing a physical challenge in response to a growing sense of their own mortality. Whatever the specific motivation, the underlying need is usually one of wanting to gain some sense of control back in one’s life, some sense of mastering the odds.

“Whatever the specific motivation, the underlying need is usually one of wanting to gain some sense of control back in one’s life”

In Franks’ case, he had first heard of Shikaari’s adventure as a young teenaged schoolboy. When, more than a decade later, he chose to follow in his mentor’s tracks, he was also trying to gain back a sense of self-identity after having worked years to qualify as a doctor and then switching to an entirely different field of sports broadcasting.

In the West, travel memoirs, including bicycling ones, have become rather a successful sub-genre. There is something about being a road warrior — whatever the vehicle of choice — for an extended period of time that brings a meditative, even transcendental, quality to one’s musings and explorations and makes them intriguing reading matter for even armchair warriors. Of course, most of the epiphanies that happen on the road have to be teased out much later because, during the journey, there are more immediate and mundane matters to be dealt with — from selecting and managing one’s mode of transport carefully, to finding food and board along the way, to warding off various potential safety hazards, and a whole lot more.

Rather than a custom-built, fully rigged-out touring bicycle as many cycling adventurists typically choose, Franks depended on a simple “doodhwaala (milkman) cycle,” which he christened “Nautanki.” (The word traditionally means drama/theater but, in contemporary slang, it is used to refer to a person who is overtly dramatic.)

Having trained and practiced with Nautanki for several weeks before the trip, he came to see her as an essential part of himself. Along the way, the bicycle proved to be more than a steadfast companion despite the various inevitable bumps and stumbles.

“Franks depended on a simple ‘doodhwaala (milkman) cycle,’ which he christened ‘Nautanki.’”

A film crew traveled alongside him in a well-equipped Innova (a popular multi-utility vehicle in India.) The resulting documentary, It’s Not About the Cycle, won the Best Adventure Film at the 2017 Toronto Beaches Film Festival.

And the highways were filled with colorful dhaabas at suitable intervals. Even the villages/towns they detoured into from time to time brought forth warm, hospitable, curious folks who opened their homes and hearts to offer their simple fare to the best of their abilities.

Whether it was a good-hearted prostitute who mistook Franks’ request for a place to rest, a proud sarpanch who showed off his tiny village’s warts-and-all beauty, a penniless dhaaba cleaning boy who insisted he would become a big city man someday despite having to give up his schooling, or a guru-like ashram leader giving sexually exploited women new beginnings, the everyday philosophies these people shared, not always explicitly, quickly wove their way into Franks’ own approaches toward cycling and life. As the physical milestones flashed by, so did particular themes: endurance, discipline, ambition, humility, focus, preparedness, temperament, teamwork, attitude towards failure, privilege/entitlement, and a whole lot more.

Sometimes, Franks pushed away nagging questions out of sheer frustration at the incomprehensibility of what he was seeing/hearing (for example, the huge wealth inequality, political chaos, law mismanagement, etc.) But, more often than not, he was simply not in the right place, cognitively, to process it all at the time. As one of his friends rightly emailed him during the trip: it would take him years to make sense of everything he was going through in this cycle yatra.

“It would take him years to make sense of everything he was going through in this cycle yatra.”

Some epiphanies came through clearly — for example, how his most-planned events/meetings (like trying to meet and play badminton with world champion Saina Nehwal) never took place the way he wanted them to while the several unplanned detours were the most interesting and enriching. Some struggles remained unexplored — like his internal conflict with wanting to be an eternal, aimless drifter versus the need to achieve certain life/trip goals.

Given how this memoir was written some years after the journey, it would have been made for more compelling reading if further layers had been peeled back to uncover braver, deeper insights. Shallow self-introspection, on the page, tends to sound more like self-obsession. It might also have helped if, along with reading Shikaari’s cycling diary, Franks had set aside time at the end of each day to freewrite his own. And, as this was not a solitary adventure, it might also have been worth including different perspectives from the film crew members.

The narrative structure is rather uneven in places. There is a fair bit of reportage-like “this-happened-then-that-happened” and “he-said-then-he-said” in the descriptions. We did not need to know of every chai break and every sunrise/sunset. A surfeit of mundane, cliched details do not make for an immersive reading experience. This is, of course, a common problem with some debut books.

“Nautanki Diaries stands apart with its earnest sincerity and exuberant love for cycling as, beyond a sport activity, a metaphor for life.”

There is an art and a skill to balancing compression with expansion and showing with telling at just the right points in the story to create appropriate dramatic tension, align cohesively with the larger, overall themes, and keep the reader engaged. These aspects come about either with a good editor’s help or more close readings of other well-written books. At times, an inconsistent voice — where Shakespearean English with words/phrases like “eventide” and “on the morrow” and “jocular” and “yore” jostled beside more contemporary slang — jarred. And, finally, a bunch of easily avoidable copy-editing errors niggled.

In the end, though, this was clearly a difficult, admirable, and, eventually, rewarding journey. No doubt, Franks will be unpacking the lessons learned for some time yet. And, while there has lately been a growing number of small-town India travel memoirs, Nautanki Diaries stands apart with its earnest sincerity and exuberant love for cycling as, beyond a sport activity, a metaphor for life. Certainly, it is worth spending a few hours to take this charming journey with the writer and let his beloved Nautanki reveal and redefine both exterior and interior landscapes for us readers too.

***

Jenny Bhatt is a writer, literary translator, and reviewer. Her first short story collection is due out in 2018 (Yoda Press) and her first literary translation is due out in 2019 (Harper Collins India.) Her writing has been nominated for Pushcart Prizes, Best of the Net Anthology, Best American Short Stories, and has appeared or is upcoming in various literary journals across the US, UK, and India, including an anthology, ‘Sulekha Select: The Indian Experience in a Connected World.’ Having lived and worked her way around India, England, Germany, Scotland, and various parts of the US, she now lives between Atlanta, Georgia, USA and Ahmedabad, India. Find her at: http://indiatopia.com.

Additional reading & watching:

Interview with Franks: Getting on a cycle is a tremendous act of independence

Excerpt: This man cycled for 22 days from Bengaluru to New Delhi (and wrote a book about it)

Film footage from Franks’ journey featured in a music video directed by It’s Not About the Cycle‘s Achyutanand Dwivedi: