Preeti Mistry has been on the American restaurant scene for some time now. The Oakland-based, James Beard nominated chef trained classically at Le Cordon Bleu in London before becoming head chef at Google. She first gained national recognition as a contestant on the show Top Chef before she opened the Juhu Beach Club restaurant in Oakland, California, where she cooked Indian food her way.

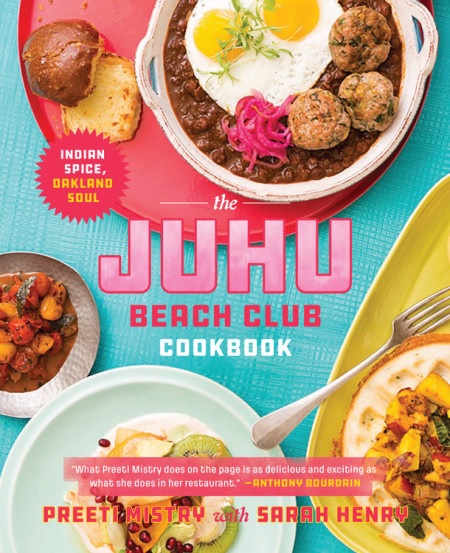

It is ironic then, that she released her first cookbook, The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook: Indian Spice, Oakland Soul (Oct. 2017, Running Press), on the eve of its closing. The restaurant, which evolved into its current icon status from a pop-up style joint, was lauded by locals and critics alike; TV host and chef Anthony Bourdain even did a segment on the restaurant on his CNN show, Parts Unknown for the “Bay Area” episode.

However, one look into The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook, by Preeti Mistry with Sarah Henry, explains to the reader why the continued existence of its namesake restaurant is irrelevant; the book is Mistry’s victory lap. She presents, beautifully but unfussily, the directions to cook the food that made her a star. At the outset, it becomes clear that The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook is not meant as a primer for those unfamiliar with Indian food at all, or uncomfortable in the kitchen; the reader is expected to bring some of their own knowledge and expertise when cooking with Mistry.

The book contains a brief instructional section in the beginning, mostly to familiarize readers with Mistry’s preferred ingredients, from Desi pantry staples, such as basmati rice and chickpeas, to specialty spices such as amchoor and black salt. She also includes recipes for base ingredients, such as ghee and tamarind paste, that are found again and again in recipes throughout the book.

“Pavs have their own dedicated section, ranging from the familiar vada pav, to the more unexpected, such as the playfully-named shrimp po’bhai.”

From there, the book is divided into its individual chapters, each outlining a particular style of cuisine found at Juhu Beach Club. The restaurant, which was known for its variety of pav dishes, is reflected in the book; pavs have their own dedicated section, ranging from the familiar vada pav, to the more unexpected, such as the playfully-named shrimp po’bhai. Also included are sections on starters and street eats, mains, drinks, and Desi-inspired desserts, among others. Select recipes also include Alannah Hale’s gorgeous, glossy photos of the finished dishes, increasing the draw of the recipes themselves.

Perhaps the best parts of the cookbook, however, aren’t recipes at all — they’re the snippets of exposition Mistry has tucked away among the chapters, starting with the forward. In it, she explains how Juhu Beach Club came to be; first as a pop-up, which gained a cult following, then surviving the struggle to find financial backing and an appropriate space, to becoming a flourishing Oakland landmark. Through each of the following chapter introductions and asides, Mistry gives us glimpses not only into her culinary background, but the parts of her personal life that have informed her journey as a chef.

“Mistry gives us glimpses not only into her culinary background, but the parts of her personal life that have informed her journey as a chef.”

She describes her first memories of visiting Juhu Beach — the famous Mumbai beach for which her restaurant is named — and becoming intrigued with Indian food for the first time. She describes dropping out of college, meeting her now-wife, and squeaking by in her early 20s on a limited budget and limited space to feed friends and family alike with joy — all experiences she brings to the kitchen as a professional chef today.

As the book progresses, the recipes become more involved, bit by bit — and so do the stories. Although many of her anecdotes are universally relatable, as a Desi-American reader, my favorite asides were perhaps Mistry’s stories of her teenage years. She recounts her adolescence in the Midwest, growing up in a household full of traditional Gujarati food, and describes the experience of eating the Indo-Ugandan cuisine that characterized the Mistry family dishes (her father’s side of the family emigrated from Gujrat to Uganda, where her father was largely raised, and her family had spent a considerable amount of time there prior to her birth), while thinking longingly of “outside food” — restaurant food.

“She recounts her adolescence in the Midwest, growing up in a household full of traditional Gujarati food…while thinking longingly of ‘outside food’ — restaurant food.”

Her descriptions sound instantly familiar; the comparative exoticism of even places such as Burger King after day after day of home-cooked meals; the longing for the “regular American” fast food or diner experience, is one that, I suspect, is shared by many children of immigrants. Once on her own, she describes being drawn to the meat-heavy dining experiences typical of American fare, and becoming passionate about the American restaurant experience; all while maintaining her sense of awe for the street food of Juhu Beach.

Based on these experiences, then, Mistry makes an excellent point about authenticity, especially in the realm of Indian restaurant cuisine. She argues that Indian food has been pigeonholed; people expect it to look a certain way (naan, rice, curries, etc.) and become mistrustful or upset if presented to them differently because it does not seem “real.”

Mistry posits that this viewpoint is nonsense. That setup may be one way to present Indian food — perhaps the predominant way — but it does not reflect the experiences of chefs such as Mistry, and therefore is not authentic to her. The way she chooses to present Indian food, in her restaurants and in her cookbook, are the way she has experienced them — and while the way she presents her food may not be considered “traditional” by purists, it reflects a deep affection for the Indian cuisine that she grew up with.

“While the way she presents her food may not be considered ‘traditional’ by purists, it reflects a deep affection for the Indian cuisine that she grew up with.”

Affection may, in fact, be the unifying theme of The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook. The fact that Mistry includes recipes for things as simple as ghee, and tamarind paste — things that even seasoned chefs are content to source from the grocery store to save a couple of minutes — shows her belief that to produce high quality dishes, care must be taken in every step of food preparation.

In the book, she mentions that she went a step further at her restaurant — something she calls “hyper-local” sourcing. In her quest to get the freshest, highest-quality ingredients for her restaurant, Mistry pairs with local farmers for her produce, thus weaving Juhu Beach Club both into the local culture, and the local economy of Oakland. And although she does not expressly ask the reader to do the same, the recipes for each chutney, each masala mix, are so painstakingly written to optimize the flavor of each dish, that it would seem a shame to settle for insipid ingredients. The Juhu Beach Club process would be present in the final product, but not its soul.

“The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook is so much more than a list of recipes. It is one part cookbook, one part autobiography, and all parts philosophy.”

The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook is so much more than a list of recipes. It is one part cookbook, one part autobiography, and all parts philosophy — philosophy about what it means to eat well, what it means to be a part of your community, and what it means to navigate between the culture you live in, and the culture you come from — sometimes with awe, sometimes with annoyance, but always with love.

In a world where we have become so accustomed to celebrated chefs and culinary cultural icons being men — even if more and more people of color are gaining recognition in the culinary world, they are, for the most part, men — a queer Desi woman from London and Ohio and California brings much-needed, unpretentious perspective. So, even if you don’t cook, come to The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook for the stories — and stay for dinner.

Read an excerpt of The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook, or hear Chef Mistry read from it. Find Mistry on Twitter @chefpmistry, and visit the website for Juhu Beach Club.

***

Rashmi Venkatesh is a pharmacologist who now works behind a desk and lives in the Metro D.C. area. Her interests include feminism, pop science, South Asian diasporic culture and media, and biryani. Find her on Twitter at @rashmiv11.

More on Food at The Aerogram:

Chefs, Cookbooks, Reviews

Vibrant India — A Tip Of The Hat To Delicious Ingenuity

Review: Bollywood Kitchen by Filmmaker and Author Sri Rao

An Adventure In Taste: Trying Out Saffron Fix’s Ready-To-Cook Meal Kit

Chaat Wallah-in-Chief: Meherwan Irani

Queen of the Hill: Asha Gomez

Culture, Commentary, & More

Here’s Why We Need To Stop Calling Pumpkin Spice A “White People Thing”

The Chaiwala, The Butcher & The Other: Food, Fetish, & Class Online

‘Breaking Barfi’ and Reflections on South Asian Eating Habits

Food is the Tie That Binds and Nourishes the Soul

Short Film: ‘Pithas in Barahipur’ Captures a Slice of Village Life

A Brown Table Brings Brown Hands To Food Photography

Tales Of Turmeric, Spice Of My Heart

Karachi’s Comfort Food Delights

Falooda May Be The Most Psychedelic Dessert on Earth

McSpicys are McYummy: The Joys of Eating Fast Food Abroad

The Chai Wallah Chronicles: Telling the Stories Behind Each Cup