In 1961, Bharati Mukherjee moved from India to Iowa. She was in her early 20s and single. With a recent master’s degree from the University of Baroda, she had come to earn her MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

In 1961, Bharati Mukherjee moved from India to Iowa. She was in her early 20s and single. With a recent master’s degree from the University of Baroda, she had come to earn her MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

What it must have been like for a young Indian woman to plop into the American heartland of 1961!

Mukherjee, who passed away on Jan. 28 after a career writing tales about immigrant life, probably doesn’t fit many people’s stereotypical image of the Indian immigrant woman in America. Often it’s the man — the husband — who is seen as the primary immigrant, whether he’s a doctor, IT professional, or Kwik-E-Mart owner. The Indian immigrant woman is the trailing spouse, following along. In many of Jhumpa Lahiri’s masterful stories, for example, the Indian immigrant woman is the lonely wife, isolated as a homemaker in an alien country.

While there’s truth to this image, there’s also an understudied group of Indian immigrant women — those who came to America not as someone’s spouse or relative, but as independent women to pursue higher education or career opportunities. And it’s these independent Indian immigrant women who are the primary focus of the recent book Indian Immigrant Women and Work: The American Experience, by Ramya M. Vijaya and Bidisha Biswas.

For their research, the authors conducted structured interviews with around two dozen Indian immigrant women who came to the United States for work or study. Nearly all were unmarried when they arrived. Some came to America as early as the 1970s; some came as recently as the 2000s.

Despite spanning a range of generations, career fields, and family and geographical backgrounds in India, common patterns emerged. Indian women by their early 20s would hit a “combined personal and professional wall.” Their families would go only so far in encouraging their educational and career goals. At a certain point the women were expected to give it all up for a traditional wedding and family life. One woman said, “I did see my friends get married in India, and I didn’t want that.” Another woman said, “My sister was married at 21, arranged at 17. I was in class 8. I was devastated by that; I did not want an arranged marriage.” Facing this wall in India, the women saw immigration as “a tool to expand choices,” as the authors put it.

While many of these women did say that their mother or an older female family member supported their desire to go overseas, the decision to come to America for work or education was often ultimately a small act of rebellion as life’s choices narrowed. The authors describe this as an example of “micropolitics”: how change happens through “the everyday lived experiences of individuals questioning and challenging limitations.”

“The decision to come to America for work or education was often ultimately a small act of rebellion.”

Once in America, the women in this study encountered many opportunities, but also some challenges. For example, learning how to be assertive. “Indian women are bred to be meek, to be good listeners,” said one woman with an MBA from a highly regarded Indian institution. Then there’s the “culture of going out at night.” Women across generations mentioned their unease with American drinking culture. For example: “I don’t drink much; that’s a big part of work-based socialization in the U.S. I feel like I have missed out on networking because of that, because of my lack of interest in happy hours.”

There are also gendered challenges to fitting in. Due to U.S. immigration policies and Indian education policies, the majority of the women in this study had a background in science or technology fields — mostly male-dominated arenas. The women commonly mentioned that sports talk was an impediment to integrating into American workplace culture. “I feel that Indian men solve that problem quicker because they talk about sports more easily,” one woman said. Some women said they scan sports magazines so they can at least have surface-level chatter at the office.

“Reading this book made me really appreciate and admire these pioneering women.”

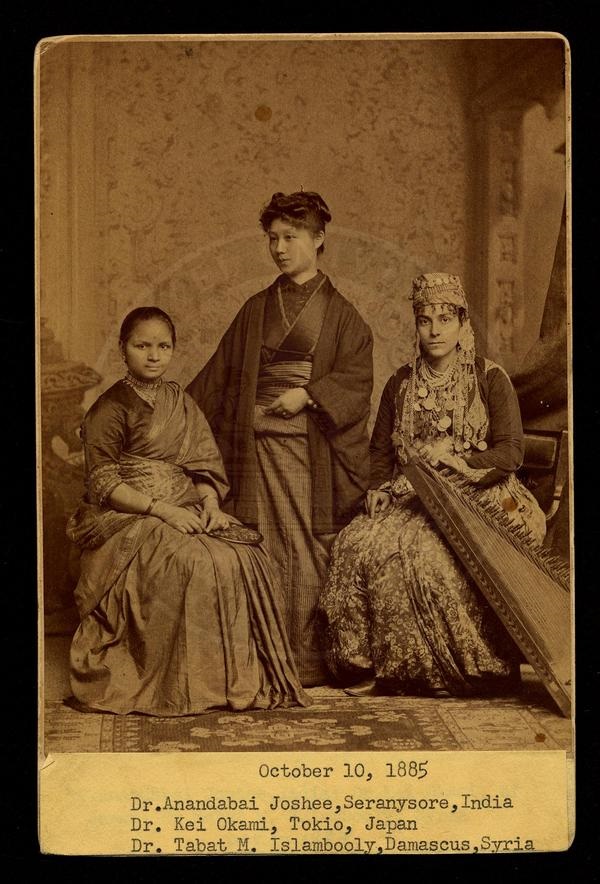

Reading this book made me really appreciate and admire these pioneering women. They left home at a young age, all alone, and encountered a new country with customs and a culture that were unfamiliar to them. They often studied and worked in fields that were male dominated, which is hard enough if you aren’t an immigrant. Back home in India, they were seen as aberrations — women who didn’t take the normal life path.

In conducting this study and writing the book, the authors have made an important contribution to better understanding independent Indian immigrant women. Each woman made individual decisions that pushed the limits of what was considered the norm for an Indian woman, and together these micro-level acts have contributed to larger societal changes that have expanded opportunities for women.

(One thing to be aware of about this roughly 95-page book is that it’s from an academic publisher, which means it’s kind of expensive — around $60. Borrowing it through a university library or obtaining it through interlibrary loan might be the way to go. If you’re interested in the topic of this book, you can also watch this video, in which Vijaya talks about the findings presented in the book.)

The immigration story of Bharati Mukherjee to Iowa is no longer quite as unusual as it must have been in 1961. Each independent Indian immigrant woman’s personal decisions have paved the path for other women to pursue their own journeys.

* * *

Preeti Aroon (@pjaroonfp) is a Washington, D.C.-based copy editor at National Geographic and was formerly copy chief at Foreign Policy.