“Get out of my country.”

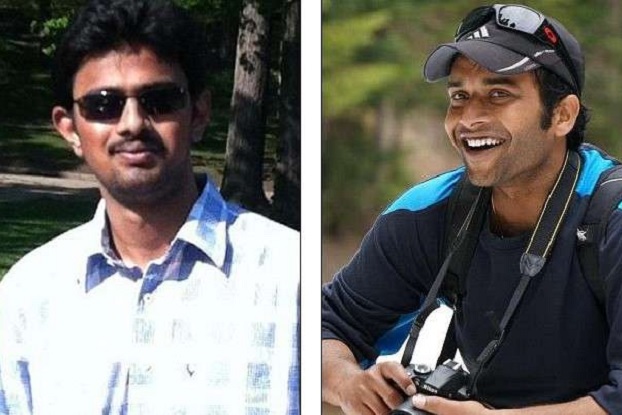

The phrase, familiar to many, was uttered Wednesday night, when a white man opened fire inside a bar in Kansas City, injuring Alok Madasani and killing Srinivas Kuchibhotla.

The two men were of Indian origin and worked at the Garmin headquarters nearby.

Major news outlets reported on the tragedy, and public outcry was swift, with over $1 million raised for the victims’ families.

Despite attempts by Trump and his supporters to minimize and act as if such incidences are anomalies, across the country, communities are confronting the climate of hate and fear.

“Across the country, communities are confronting the climate of hate and fear.”

Since the election, countless Americans have joined protests, and voiced their support for immigrants and POC. Among South Asian Americans, questions of identity and our place in the U.S. are being raised, and discussed openly.

Yet, the political moment requires us to dig deeper and to break away from the usual tropes of safety and the right to live the American Dream.

If we are serious about fostering a society that no longer operates on oppressive hierarchies, we must re-frame and re-orient the national discourse, especially as South Asian Americans. Otherwise, any chance at social change will only benefit the privileged among us, and the system will continue to perpetrate harm on the marginalized.

. . .

Currently, the mainstream discourse on the shooting in Kansas City, and the overall view of immigrants, and POC, is still constrained by tropes of the “good” citizen, or “model minority,” versus the undeserving. Or it seeks to paint an America that’s far removed from what it’s traditionally been: a utopia where equality and acceptance was the norm.

A casual glance at American history would reveal all this to be fantasy. The U.S. has been antagonistic toward POC, placing whiteness at the top of its economic and political structure. White Americans have benefited from a system that’s offered them “positive rights” while denying opportunity and access to resources to others.

Most importantly, regardless of whether someone works, or is unemployed, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, black or brown, queer, gender non-conforming, likes to get high and sit on the couch all day, or finds joy in waking up early and writing while it’s dark outside, no one deserves to be shot and killed based on how they look.

This last point bears repeating, as many of us, especially in the South Asian American community, begin to open up dialogue on issues of racism, xenophobia, and hate. We must avoid sticking to conventional narratives, that seek to center the tragedy as one that’s horrific because the victim was a professional, or that he was a “good” immigrant, or a “model minority” in a white-collar neighborhood. Doing so limits the perspective of what’s actually been happening in the country.

“For years, the level of Islamophobia has been spreading. What was once a fringe movement has now found a home in the White House.”

For years, the level of Islamophobia has been spreading. What was once a fringe movement has now found a home in the White House. Trump has appointed right-wing anti-Muslim bigots to his cabinet. One of the first actions he’d taken was to install a “Muslim” ban, thus affecting the lives of countless people who happen to hail from certain Muslim-majority countries.

Mosques have been attacked. Muslim Americans are also the target of abuse and harassment. And according to some reports, the shooter in Kansas City described his victims as “Iranian people.”

Again, the tendency might be to restrict ourselves to the dominant discourse, stating unequivocally, as white-collar South Asian Americans and specifically, Hindu Americans, that we are not Muslim, and that we abhor terrorism, and only want to live and work, and go to school, and proceed as upstanding citizens. However, as a Hindu American myself, I also believe that differentiating ourselves from Muslims, from “other” poorer immigrant or brown and black communities, is not only naïve, but mean-spirited, and selfish, and will serve to perpetuate that damaging discourse for decades to come.

If one is truly invested in social justice, it is critical to expand and dismantle that dominant discourse, to go beyond what is expected. This means framing ourselves, as South Asian Americans and Hindu Americans, as not just victims of a horrible attack, but as true allies to the politically and socially marginalized, such as Black Americans and undocumented immigrants.

And we must base our response not as a worry that if we don’t stand up for others now, we might be next. Such an approach is cold and calculating, and inhumane. To completely destroy the damaging discourse, embrace empathy and caring instead. This will lead to new perspectives and conversations dealing with substantives issues, such as Islamophobia within South Asian American Hindu households, and our own history of anti-blackness.

. . .

“The murder of Kuchibhotla should open us up to the tough and difficult conversations of dismantling all oppression.”

In “Deviance as Resistance: A New Research Agenda for the Study of Black Politics,” professor of political science, Cathy J. Cohen, encourages academics and writers to learn from black queer theory and black feminism as a means of enriching the study of African American politics, and of resistance. By incorporating queer and black feminist perspectives, one can challenge norms of nuclear families, and the stereotype of single women as lacking agency. “I am suggesting that through a focus on ‘deviant’ practice we are witness to the power of those at the bottom,” she explains, “whose everyday life decisions challenge, or at least counter, the basic normative assumptions of a society intent on protecting structural and social inequalities under the guise of some normal and natural order to life.”

The murder of Kuchibhotla should open us up to the perspectives of fellow outsiders, to root ourselves to the tough and difficult conversations of dismantling all oppression, including caste and patriarchy.

In times like these, when anxiety and fear is on every corner, empathy and a recognition of humanity in others is truly revolutionary.

* * *

Sudip Bhattacharya lives in New Jersey, and he is a second year Ph.D. student in political science at Rutgers University who focuses on race and identity in my research. Prior to joining the program, he was a full-time reporter. He still writes articles and stories, and his work has been published at CNN Politics, the Washington City Paper, Lancaster Newspapers, The Daily Gazette (Schenectady), The Jersey Journal, Media Diversified/Writers of Colour, AsAm News, Reappropriate, The New Engagement, and Gaali Gang.