Here’s one distinct mark of success for a comedy act in the digital era: eager to amplify its genius, you forgo the passive evangelism of spreading a clip online, and instead summon office mates to your desk to indulge in shared viewing.

For me, this scene played out repeatedly with comic Hari Kondabolu’s skit about the event he’s dubbed the Indian Superbowl — otherwise known as the National Spelling Bee.

Kondabolu dedicated a segment on the late night show Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell, for which he’s been a writer since last year, to Bee winner Arvind Mahankali, who is, naturally, South Asian, and possesses an adorable nerd swagger.

Kondabolu’s skit features several highlights of Mahankali’s win. In one, confetti rains down on Mahankali, who stares up at the ceiling impassively, hands in his pockets as though he’s taking a stroll in the park. Kondabolu plays the clip and then yells into the camera, “That is so G!” For some South Asian Americans, the Bee sparks a mixture of pride on behalf of precocious young brown brethren and sistren, and wariness about this highly visibly reinforcement of the dreaded model minority stereotype. Kondabolu unequivocally celebrates the phenomenon. “Six titles in a row!” he crows. “You can’t stop us!”

But in what can only be called typical fashion, he wastes no time lampooning the xenophobia that feeds these desi insecurities, starting with a Tweet he’s found about the Bee’s finalists that complains, “America has to step it up with our spelling game. Last three remaining all of Indian decent (sic).”

“First of all,” Kondabolu glowers, “these kids of Indian descent ARE ALSO AMERICAN.”

“Secondly — you spelled descent wrong!”

On the projection of the Tweet magnified on the screen behind Kondabolu, the word “decent” is circled in red, and scrawled below it, “DESCENT. See me!”

This mix of outrage, mockery, glee, and political critique is trademark Kondabolu, and it’s helped him establish a cultish, and growing, fan base. He spoke to me recently about how playing to a desi-filled room is like being stuck at your parents’ parties; the oppressiveness of being labeled a “conscious” comic; and recording his first live album this week.

On Developing His Own (Accent-Free) Style

Nishat Kurwa: Why do you think so many Asian Americans support comics like Russell Peters doing “the accent thing” when we have so many other options?

Hari Kondabolu: I think Russell Peters is a pioneering figure. I’ll say that right off the bat. The first time I saw him was on a Canadian special that leaked on the Internet. And it blew my mind. It was one of the biggest things up to that point that changed me. Just the idea that he’s on TV somewhere, and they were laughing at the things he was saying, and it mattered.

His style, that’s not my style, and it’s not a style that I’m not necessarily influenced by or appreciate. I can appreciate people that do appreciate him, but he hasn’t been an influence to me. [pullquote] [Russell Peters] also created a market. Because of him, brown people are seen as people who have money to spend on comedy.[/pullquote]But in the context of one being the first, which is a very big deal — the first is always the hardest — he’s very important.

Also, most of those audiences are East Asian and South Asian. For a lot of people, he was the first person that they connected to, that brought them to a comedy club, which a lot of times, for oppressed people, is not a place they’d find safe. When you look at those audiences, you have to remember it’s not mostly a white mainstream audience. It’s mostly a minority audience — he’s our guy. The context he comes in needs to be seen and appreciated. He also created a market. Because of him, brown people are seen as people who have money to spend on comedy. That has to have an impact.

In terms of why people will support that, it’s a bit more straightforward, right? It’s accessible. Me, that’s not what I do. So certainly, I’m not going to draw the same numbers at this point that Russell Peters is, or other comedians who are also maybe a bit more straightforward in their style and approach. One thing I’ve also understood is, maybe I don’t want everybody. Because there are folks who come to my show sometimes because I’m a brown comedian, and they’re excited, and they don’t get it at all. I’m not reaching them in a way they can understand. I can’t give them what they want, and that’s ok. Cuz not everything is for everybody.

I’m proud to say that there are enough people that do appreciate what I do, and they come out when I go to their towns, and hopefully that number will grow.

NK: Have you gotten advice to make your act more accessible — to de-politicize your work? How did you deal with that?

HK: My mom has always said, you need to write some stuff that’s more accessible and then mix the other stuff in with it. That’s an approach. The approach is, you give them a little sugar, and then you hit them with something harder. I’m not totally against that approach. But I think what’s sugar to me is not necessarily sugar to other people.

[pullquote]I get called smart as much as I get called funny.[/pullquote] Also, I feel if you’re a comedian with a distinct style, to do something that’s not particularly who you are, it actually kind of breaks the rhythm of the act, like, “It got a laugh, why’d he throw that in there?” At the end of the day, there are comics who will go onstage and make people laugh a lot harder than I will. I’ve accepted that. I’ve been around enough to know what my crowd is.

I get called smart as much as I get called funny. I understand that. I get it. It’s annoying, I‘d rather just be funny. But I also know I stand out. I’m doing something no one else is doing, and I’m proud of it. They’ll remember me. And that’s a big part of this. There are folks too, that don’t necessarily get it the first time around, and watch clips of me online, and all of a sudden they find it. Or there are shows where there are 100 people there, and I’ll make maybe half of them laugh, and those 50 people who will bring 50 people the next time around, and the show’s even stronger. A lot of this is perseverance.

On His Parents Being Parents

NK: I read something you said about your parents…it equated the assumption that Indian parents are opposed to arts careers with other stereotypes about South Asians, like the ones about arranged marriage. It sounds like your parents have been really supportive of your comedy career. But were they worried when you became politicized…or, are they politicized themselves?

HK: I don’t think my folks were worried that I became politicized. I don’t think they’re particularly politicized people; they both, in their own way, do things that can be read as political acts. But it’s not with the overt, like, “I’m doing something political.” They’re proud people and they’ve overcome a lot as immigrants who’ve had to work their way up.

But just to backtrack a second, it is interesting; I’ve seen people that ask me, “How do your parents feel (about your career)?”…and it’s brown people that do it, really.

NK: Yeah, many of us (South Asians) have parents that love us for, and accept (our creative careers), and let us grow.

HK: And maybe they didn’t at a certain point. We evolve as human beings and so did they. To assume that who they were at 35, or 40, is who they are at 60 is foolish. And also, my mother has now spent more time in this country than in India. This is home now, this has been home a long time. My mom’s a U.S. citizen. Not all parents are the same, and everybody has a different set of experiences, but my folks have adjusted. And it’s hard — my brother and I have both chosen unconventional career paths. Certainly I’m sure they wished we chose something more stable. That’s a parent being a parent.

Whenever I see brown comedians talking about their parents in overly simplistic ways, and using accents, I’m like, “Cmon!” Here’s the thing, I understand the idea of authenticity, when you’re doing a bit. I find it questionable depending on who’s in the audience.[pullquote]I understand the idea of authenticity, when you’re doing a bit. I find it questionable depending on who’s in the audience.[/pullquote] Like, I will do that when I have a brown majority audience. Because it becomes a thing where, when you’re performing for other brown people, and you’re doing accents, you’re sharing an experience. It almost feels like your parents are having a party, and you’re a kid, and all of a sudden all the kids who are the kids of their friends are all hanging out because they basically have to kill time until the party’s over. You’re all doing impressions and making fun of your parents and making fun of school and making fun of your lives. You might not see those people again, but you connected over this.

That’s what it feels like when I do a show with mostly South Asian people; we’re all in that back room, we’re all just hanging out, waiting for that party to end. It’s a beautiful thing, and I’m not going to shy away from those situations. I read a room like every comic reads a room.

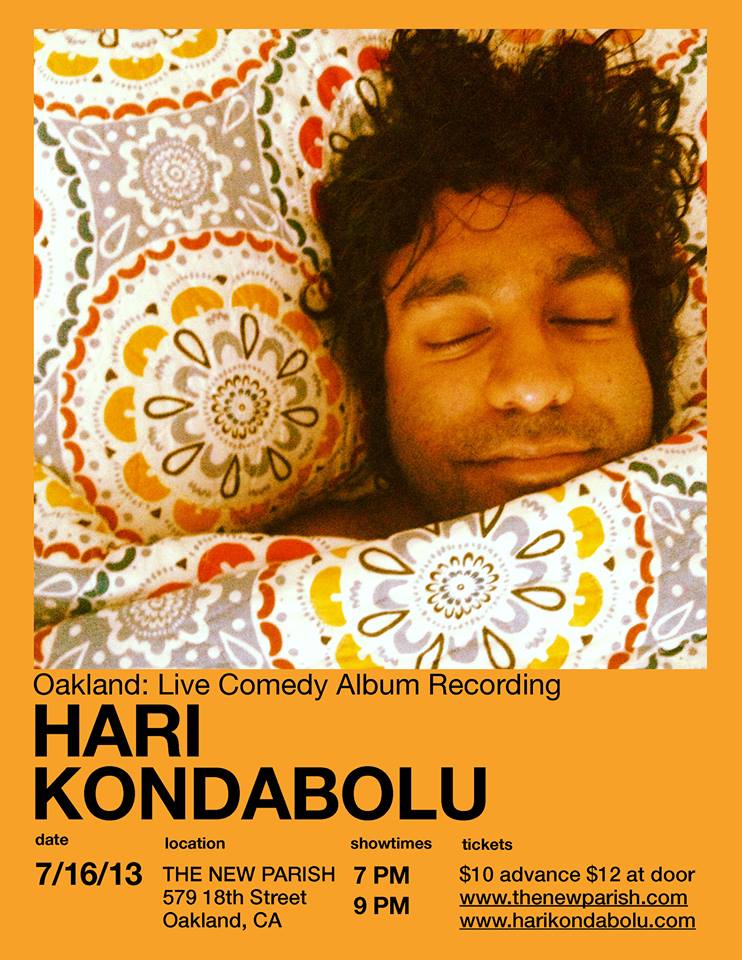

On His Album AKA His First “Public Statement”

NK: What do you hope comes out of the album? Is it gonna to get you your Lambo?

HK: I don’t know…I’m not going into it with that. For me, being a comedian means that you release albums. Authors write books, comedians make albums or specials. They make things that document a particular era or they make their statement. To me, this is my first public statement. And I want to share this the way it’s being released. That’s why I’m putting this out. If it leads to more, that’s great, sure.

You know, I don’t even know how comedy albums are really consumed anymore. Comedy fans will listen to the whole thing. I mean, there will be jokes that you can just buy on iTunes, but I want people to listen to it from beginning to end.

To me, I’m writing this thing the way I think about it on stage: “How do I keep an audience enthralled and focused, and don’t lose them and kinda shift? Is my tone too harsh here?” All these dynamics that come with live performance, and I want that to come across on the album. I’m hoping to have callbacks and references to things within the structure of the piece. Let’s say you listen to a joke, and you’re like, “What is he referencing, I don’t know what he’s referencing?” Because it was from 20 minutes ago, and something that’s linear.. Something that you can’t just pick up in the middle. You’ll get it, but it’ll make more sense as a whole. Because I’m a human being that has shared something for an hour.

It’s like walking in on somebody mid-conversation. You might get it, but you might not get the richness of it. Because you don’t completely know who I am when you walk into the conversation, and that’s what I’m hoping to give in an album.

My hope is that we meet somewhere in between.

Kondabolu records his first live album this Tuesday at the New Parish in Oakland, CA.

You can follow Nishat Kurwa on Twitter @nishatjaan.