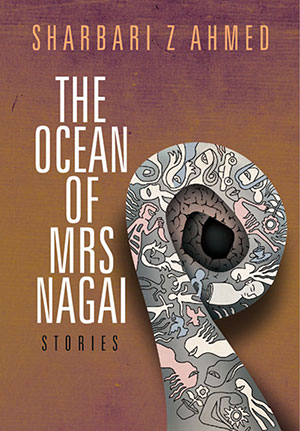

True to the aesthetic of the short story form, The Ocean of Mrs. Nagai: Stories is a collection of carefully crafted slice-of-life moments, which to experience the reader must first be invited in, led through then out by a guided hand. Sharbari Ahmed’s characters do precisely so — they stop to notice you, and while at first they seem reserved, they quickly transform from being strangers into storytellers, openly revealing their pasts and the inner workings of their present.

True to the aesthetic of the short story form, The Ocean of Mrs. Nagai: Stories is a collection of carefully crafted slice-of-life moments, which to experience the reader must first be invited in, led through then out by a guided hand. Sharbari Ahmed’s characters do precisely so — they stop to notice you, and while at first they seem reserved, they quickly transform from being strangers into storytellers, openly revealing their pasts and the inner workings of their present.

“Ahmed’s characters . . . quickly transform from being strangers into storytellers, openly revealing their pasts and the inner workings of their present.”

The book is a beehive of cultural landscapes, not owing to the number of places Ahmed travels us to — though indeed, each city, country and culture are characters in their own right — but because of the diversity among the protagonists who inhabit these same places. Crucial to the plot of understanding pluralism, their experiences are modeled after their own differentiated perspectives. Often in the same cultural context, there are two or more opposing points of view and Ahmed grants non-judgmental access to both. Very interestingly Ahmed takes these “gossamer threads of luck and time” and reveals the sense of displacement and pressure that transpires not just from assimilation into a new culture or a cultural exchange, but also from performing gender roles as well as hailing from altered historic timelines. In doing so, she seems to highlight the blending of various roles (friend, colleague, parent, in-laws, spouse, child, neighbor, the government, political leader etc.) lived ultimately by humans with distinct thoughts, beliefs and perceptions — the polygamy of identity, if you will.

The ocean, referenced by the title, stands as a symbolic reminder of boundaries: how they can be instated, how they can be crossed. The threshold varies; there can be no emotional typecasting for two men or women of the same age or culture, let alone when permutations are in the mix. En plein air — Ahmed’s writing is similar to a painting, a still life revealed through individual brushstrokes. In the foreground the reader plays with the nuances of pluralistic identity that are whispered, but forcefully. The waves of identity are also influenced by other dichotomies such as public and private life, forgiveness and acceptance, nostalgia and modernity, aging and youth, religion and atheism, and more. The plight of the human spirit is exposed, as not only concerned with the ‘who’ or ‘what’ or ‘why’, but in Ahmed’s socially, politically and economically conscious world, the ‘how’ to be as well.

“The plight of the human spirit is exposed, as not only concerned with the ‘who’ or ‘what’ or ‘why’, but . . . the ‘how’ to be as well.”

In the very first story The Ocean of Mrs Nagai, Nyla, an artist, also the daughter of Bangladeshi diplomats and the wife of an American, describes the ‘superimposition’ she engineers in her installations by taking photographs through outdated methods and then digitizing them. Here I believe is Ahmed’s first clue about how these characters’ lives (and consequently, perhaps our own) are led — always a mix between holding on and letting go, such that what goes and what remains is arbitrary. The subjectivity of our inner existences, prepared to an extent by our external circumstances, is successfully revealed by the agency Ahmed gives her characters.

We meet Zara, a precocious ten-year-old daughter of a diplomat couple, who lives in Africa and finds herself grappling with developing notions of ‘otherness’, ultimately feeling estranged from herself and ‘her kind’. In Raisins Not Virgins, Sahar, a quintessential second-generation millennial, realizes that relationships do not exist between two individuals, but between a negotiation of two individual and plural identities. Next a child, an embodiment of curiosity itself, whose throwing things out the window to determine the differences in how they fly suggests, in essence, the early onslaught of cultural identity and conditioning.

In Sonali, a mother-in-law who seems comically ahead of her time while her daughter-in-law many steps behind it, but really, time superimposes, history repeats itself, and it is divulged that modernity does not always imply progress. The characters of Ila and Katherine, murdered in Bangladesh for being homosexual, have their presence reincarnated through their very absence as they bring their families together in love and tragedy. Ella, adopted into an American home but Bangladeshi by birth, rejecting all the parts of her she doesn’t understand in the hopes that it will make her stronger, but eventually she succumbs to the tender vulnerability of her inner child as there can be no wisdom without acceptance. Finally, Yasmina, a middle-aged mother experiencing the injustice of how having a blanket definition for race, ethnicity and religion, which takes no account of individualized belief systems — that is, racism — preludes a chaotic world order that is driven fundamentally by a lack of understanding on both sides.

As the pages of the book turn — sometimes languid, other times sharp — the progression of characters and stories as a whole follow a similar pattern to the scenes encompassed in them. We zoom in and out of the world all together, and then more closely New York City and Dhaka, with mention throughout of other cities and countries rooting themselves in the narrative like pins on a map. Ahmed fosters a true cultural conversation that announces itself in both monologue and dialogue — an accurate emotional detailing of the effects of globalization on both the young and the old, the past and the present and the ‘one’ and the ‘all’.

* * *

Dipti Anand is an poet, writer, editor and academic, living and working in New Delhi, India. To connect with and read more of Dipti’s reverie and creative work, visit www.diptianand.com.