This essay was originally published on Dr. Ali Mattu’s Brain Knows Better blog. It is reposted with permission in honor of Mental Health Month.

It starts at home. I’m doing the dishes and listening to a podcast. I’m about to rinse off when my brother walks through the front door. “About time,” I think. Salman’s been gone for a while and I was beginning to wonder when he was coming back. We put on some tea, sit down and watch an old episode of “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” making fun of Worf during the commercials.

That’s when I wake up.

I have this dream every other week. I hate it — not the dream, but being ripped away from it. Waking up is like finding out my brother died all over again.

On May 19, 2008, Salman shot himself, ending a long battle with bipolar depression. He was 36 years old. Salman suffered in silence — his illness wasn’t diagnosed until he was 34, after a very public manic episode that tore my family apart.

The dreams are always the same — I’m living my life right now in New York City and then my brother appears. Life has continued as if he never died — he was just away for a while. I’ve come to think of these dreams as a parallel universe where he never committed suicide, an alternate timeline in which he lives.

Waking up reminds me of how I found out. I got a call from my dad at 4:46 a.m. that Monday morning. I can hear his trembling voice — “Ali, your brother is no longer on this Earth — he committed suicide.”

I remember my guilt — Why didn’t I do more to help him? What did I miss? Why wasn’t I there for him?

I get out of my bed, run through my morning routine, but the pain lingers. Listening to music and checking the news helps me bury my memories.

I could be having a normal day, then someone says, “My boss makes me want to shoot myself.” It feels like waking up again. How dare you joke about that? You have no fucking idea what you’re saying! But it’s just a figure of speech to them, what can you do but shove the anger down and get out of there as quickly as possible.

It’s worst when I physically can’t get away. Days after learning about Salman’s death I flew back to visit his grave in Pakistan and shared the seat with a man my father’s age. He looked easy to talk to.

“Are you on your way home?” he asked.

“Not really, I’m going to visit my parents.”

“Ah, good for you. I’m sure they’ll be happy to see you. I was here for my daughter’s graduation — she just finished med school.” He was beaming with pride.

“Ah, good for you. I’m sure they’ll be happy to see you. I was here for my daughter’s graduation — she just finished med school.” He was beaming with pride.We talked about the medical profession and my training to become a psychologist.

“How’d you get interested in that? Were your parents psychologists?”

“It’s what I loved most in college, honestly.”

“What do your siblings do?”

“No…no siblings,” I lied, “it’s just me.”

“Oh, an only child,” he nodded. Now he wanted to talk about it! “Growing up, you must have had all the pressure from your parents.”

I had to get out of that seat. I said “excuse me,” tore off my seat belt and went into the lavatory. Not to pee, just to stand there. My heart was racing. I couldn’t tell him the truth — that I had a brother and he just died. I didn’t know why, I just knew I couldn’t do it.

When I returned to my seat, I put on my headphones to block out the older man. Despite his efforts, we didn’t speak for the remainder of the flight.

I don’t remember much from that visit. I know a lot of people came to pay their respects, but the rest is a blur. What sticks out vividly is seeing his grave for the first time. I stayed with him for an hour. I promised Salman I would keep his memory alive with his son and pass on what he had taught me. In that moment, I was overcome by the smell of fresh jasmine, as if his spirit was trying to embrace me.

After returning home to Washington, D.C., I grouped people into two categories — those who knew me before my brother died and those I met after. Friends and family gave me a wide berth, avoiding the topic of Salman’s death. With new people, I pretended to be an only child. I hated myself for lying, but the last thing I wanted was to be the guy — the therapist — with the bipolar brother who shot himself. Denying Salman’s role in my life was the quickest way to avoid the pain. With the exception of my dreams, Salman never existed.

That year I spent Thanksgiving at my friend’s home and met her sister’s future fiancé, Karl. The two of us hit it off after we discussed a mutual appreciation of Batman and Iron Man. After dessert, a few of us played board games. Karl and I joined forces and declared ourselves “Team Awesome.”

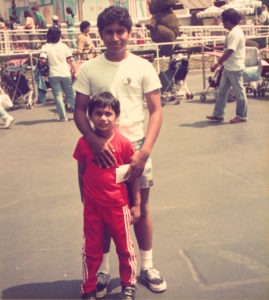

That year I spent Thanksgiving at my friend’s home and met her sister’s future fiancé, Karl. The two of us hit it off after we discussed a mutual appreciation of Batman and Iron Man. After dessert, a few of us played board games. Karl and I joined forces and declared ourselves “Team Awesome.”“It was weird growing up,” said Karl, “My brother was 10 years older than me — he was a friend and a bit of a dad.”

I wanted to say “me too”, but I didn’t, I deflected and asked, “What was that like, being so far apart in age?”

“We did a lot of things together — sports and all that stuff, but he let me hang out with him and his friends, sometimes even sneaking me into rated-R movies.”

“Sounds like fun,” I said, but nothing more. In fact, Salman did the same. He took me to a bunch of movies I wasn’t old enough to see — “Terminator 2,” “The Rock,” “The Matrix.” My favorite thing was to tag along with him to Galactican, our local arcade. He knew everyone there. It made me feel so cool just being around him.

I didn’t tell Karl any of this. I might have made a good friend that day, but I kept pretty quiet.

“You know,” Karl said, “My brother helped me decide to major in computer science.”

“That’s cool,” was all I said, but inside I was screaming, I desperately wanted to tell Karl how my brother introduced me to Star Trek, how that led me to psychology, but I was too scared. I didn’t want him, or anyone else at the table, to ask questions, to judge me, to think poorly of my family.

By numbing myself to Salman’s suicide I restricted all of my memories about him — the bad and good. Remembering the experiences we shared together made me miss him dearly.

I think about that now — if Salman were alive today, he’d clear his schedule and take me to see the new Star Trek movie. I like to believe we’re both doing just that, in the parallel universe. Maybe in that universe he’s the best man at my wedding, the uncle to my kids, and my friend in old age.

Salman ended his life in order to stop his suffering. By refusing to face my pain, I’ve prolonged my suffering.

Last year I was serving on the board of directors of the American Psychological Association. At our end of year dinner, I sat next to Melba Vasquez, a past-president of the association. After some small talk, Melba started a conversation about family.

Last year I was serving on the board of directors of the American Psychological Association. At our end of year dinner, I sat next to Melba Vasquez, a past-president of the association. After some small talk, Melba started a conversation about family.“Ten siblings!” she asked one of our colleagues. “What was that like, growing up in such a big home?”

“Jennifer, what about you — how big is your family?” Melba continued around the table, one by one.

I felt sick. I was stuck — nowhere to hide.

“Ali, what about you?”

“There were four of us, my parents and my older brother…but he died a few years ago. He had bipolar depression and took his own life.”

“I’m so very sorry, Ali,” she said. “I had no idea.”

“It’s not something I talk about.” Even as the words came out of my mouth, the whole situation felt unreal — I had never publically talked about Salman’s death before.

“That makes sense,” she said. “There’s so much stigma about suicide — it’s not something anyone talks about.” Melba always communicated with compassion and honesty — it was one of the reasons I looked up to her and why I couldn’t lie to her.

“I’ve always been afraid that people would think differently of me and my family. I had this fear that people would think I’m an incompetent psychologist because I couldn’t save my own brother.”

“I’ve felt that way at different times in my life. Clinicians are just as vulnerable to these things as anyone else.”

When I accepted that fact, I felt comfortable seeking out my own therapy.

Later that night, I told Melba the things I wanted to tell Karl — how my brother taught me to build computers, our late nights watching “Twilight Zone,” debating Captain Kirk versus Captain Picard.

Yes, as I talked about it I felt that pain, the pain of waking up, but I endured it.

This way of dealing with things has also kept me away from the people I love. I rarely speak to my parents and I’ve been terrified of calling my brother’s son. I’m ashamed to admit I haven’t kept my promise at Salman’s gravesite. The last time I spoke to my nephew he asked me, “Why don’t you call me Uncle Ali?” I didn’t have an answer for him.

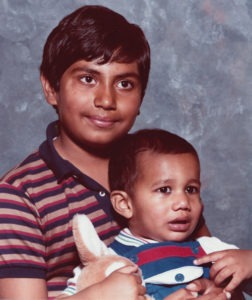

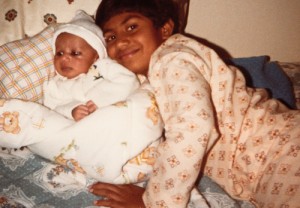

I want to be able to remember Salman more. It’s taken me five years, but I’ve finally put up photos of my brother in my home. They sit next to the other reminders of him that have always been there — the starships, action figures, video games. The photos don’t just bring me pain, they remind me of the joy we shared together.

I want to be able to remember Salman more. It’s taken me five years, but I’ve finally put up photos of my brother in my home. They sit next to the other reminders of him that have always been there — the starships, action figures, video games. The photos don’t just bring me pain, they remind me of the joy we shared together.This was written in honor of Mental Health Month and the American Psychological Association’s Mental Health Blog Day. I want to thank Razia Kosi, Executive Director of Counselors Helping (South) Asians/Indians (CHAI) for encouraging me to share my story. If you are a survivor of suicide, help is available at the American Association of Suicidology. If you are in crisis, please call 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Ali Mattu, Ph.D. is a post-doctoral fellow in clinical psychology at the NYU Langone Medical Center. He specializes in the treatment of anxiety, depression, and body-focused repetitive behaviors. Dr. Mattu writes about the psychology of science fiction at Brain Knows Better.

Thank you for opening your life to us, Ali. It is so sad for me to hear what both you and your brother have endured due to mental illness. I feel grateful for your courage in changing the story to one of wholeness…holding the choice to be vulnerable in trustworthy environments is a lesson for me as well, and also appreciating the good and the gifts that come from trauma, not just focusing on the pain. I am South Asian as well, and it makes a difference to me that you are, so that it may open a door for others of our culture to explore one’s feelings, family shame, etc., and know that they are not alone. I no longer feel like a ‘different’ South Asian for having entered therapy in my 20s and become a pschotherapist, now that my life and trusted connections center around personal awareness, self-love and love for others. Peace and blessings upon you and your journey.

Very brave and very moving