The following piece is part of The Aerogram’s collaboration with the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), which documents and shares the history of South Asian Americans.

***

YouTube video of SALGA-NYC at the 2018 NYC Pride parade.

This month, Pride parades have joyfully taken place throughout the world. One reason it’s important to appreciate these parades is that LGBTQ groups have a history of being excluded from other types of parades.

One example is the exclusion of the South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association (SALGA) from New York City’s India Day Parade during much of the 1990s. The parade takes place annually on or around India’s Independence Day — August 15.

According to a 1994 SALGA newsletter, available through the South Asian American Digital Archive, the parade’s organizer, the Federation of Indian Associations (FIA), denied SALGA’s application to march that year. The newsletter said the FIA employed “‘technical grounds’ as their vehicle of exclusion.” According to the newsletter, the FIA said that SALGA, as a South Asian group, was too broad an organization to be allowed in an India-focused parade. The FIA also said, according to the newsletter, that SALGA had missed the application deadline and had a history of disregarding the FIA’s parade rules.

The newsletter points out that Sakhi, a group that works to eliminate violence against women, was allowed into the parade despite its focus on women with South Asian, not just Indian, roots. Additionally, Sakhi and other groups permitted into the parade had applied as late as a week prior to the event, while SALGA had attempted to apply a month in advance. As for disregarding parade rules, the newsletter said that when SALGA was allowed to march in 1992 (after the city’s Commission on Human Rights intervened), it was relegated to the back of the parade and had changed positions due to safety concerns.

Such exclusion of LGBTQ groups from parades celebrating various forms of ethnic, immigrant, and religious pride was not uncommon in the 1990s. In 1993, LGBTQ Irish Americans weren’t allowed to march under their own banner in New York City’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade, and that same year, a predominantly gay Jewish congregation got disinvited from the city’s Salute to Israel parade.

In 1995, parade exclusion even made it all the way to the Supreme Court. In the case Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, the court ruled that private organizers of public demonstrations have a free speech right to exclude groups whose message they disagree with.

“The parade’s emcee even exclaimed, ‘They have a right to love!’”

In the 1994 India Day Parade, Sakhi ended up inviting SALGA members to march with Sakhi, and SALGA members carried signs protesting SALGA’s exclusion. They also passed out hundreds of pamphlets, and the parade’s emcee even exclaimed, “They have a right to love!” The newsletter said that spectators had a “mostly supportive reaction” and that the opposition SALGA faced wasn’t “the majority opinion of the South Asian community” but was “the homophobia of a powerfully-placed few.”

SALGA’s exclusion persisted through the rest of the 1990s. In 1995, SALGA was excluded because parade organizers didn’t want groups that labeled themselves as “South Asian,” according to the New York Times’ reporting.

In 1996, SALGA was excluded because the parade was open only to groups that were FIA members. Faraz Ahmed, then SALGA’s coordinator, told the New York Times that the rules kept changing and “it’s just a way of keeping us out.”

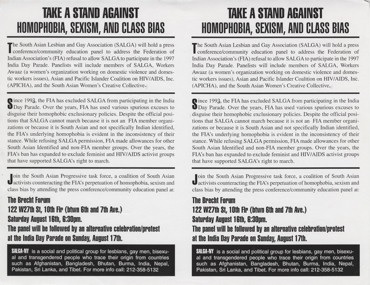

In 1997, SALGA held a press conference about its exclusion from that year’s parade, and a flyer promoting the press conference, available through SAADA, said the FIA had used “various spurious excuses to disguise their homophobic exclusionary policies.” It also pointed out that SALGA was denied participation for reasons that weren’t similarly applied to other groups, such as when other groups carrying the “South Asian” label were permitted.

Despite not being allowed in the parade, however, SALGA showed up on the sidelines for many years to protest its exclusion.

Finally, the tide starting turning in 2000, when SALGA was finally allowed to march. However, it had to obey certain rules, and the New York Times reported that it was the only group required to sign these rules. The FIA’s vice president told the Times, “We are not going to take [allow] any obscene stuff or have them walking around with provocative clothing.”

SALGA marched again in 2001 after Tom Duane, an openly gay New York state senator, took up the issue with the FIA. SALGA was once again not permitted to march in 2009, but SALGA stated in an email, “we definitely showed up and protested though.”

In 2010, after nearly a decade, SALGA was again allowed to march at the last minute after two city council members and an Indian-American congressional candidate lobbied the parade’s organizers. SALGA stated in its email that it marched again in 2011, 2013, and 2015.

Renamed SALGA-NYC in 2010, the group continues to pursue its mission of awareness and acceptance of LGBTQ people of South Asian identity. Most recently, this June 24, it marched with its banner in New York City’s Pride parade. As was proclaimed back in 1994, “They have a right to love!”

***

Preeti Aroon (@pjaroonfp) is a Washington, D.C.–based copy editor at National Geographic and was formerly copy chief at Foreign Policy.

Additional photos:

Photos by Roopa Singh: India Day Parade and Gay Pride Despite Exclusion (NYC)