The following piece is part of The Aerogram’s collaboration with the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), which documents and shares the history of South Asian Americans.

* * *

History repeats itself; thus we should learn from it.

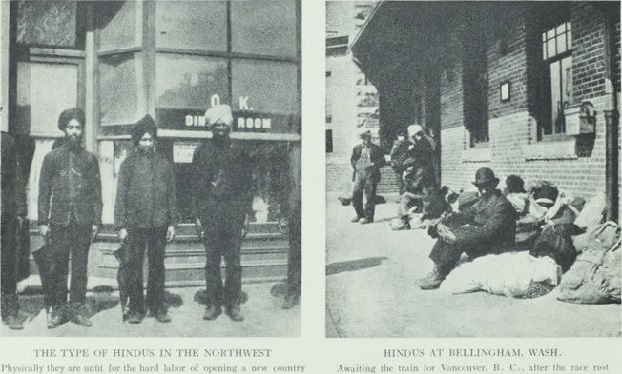

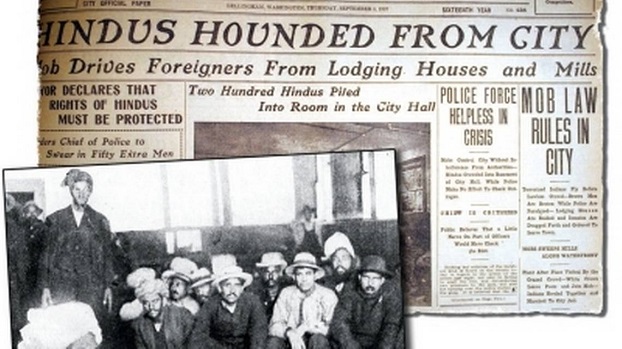

As case in point is the Bellingham riots: On Sept. 4, 1907, in Bellingham, Washington, a mob attacked South Asian laborers who worked primarily at the city’s lumber mills and drove the immigrants out of town.

A 1907 article about the riots, available through SAADA, says members of the mob “invaded” the living quarters of the “Hindus” (many, if not most, of whom were actually Punjabi Sikhs) and “completely terrorized them and forced them to leave the city.” Their belongings were thrown into the streets, and they were “herded along the streets like cattle.”

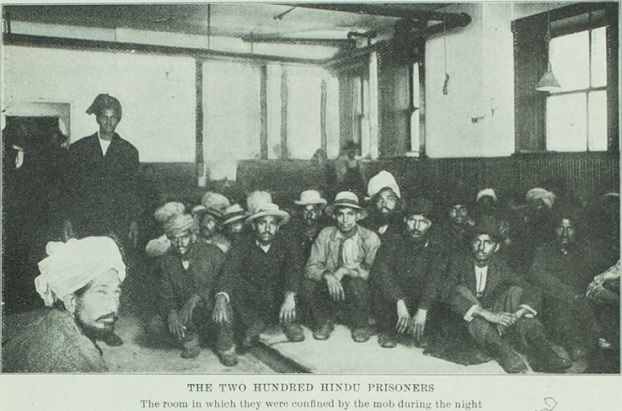

The police chief made a sort of deal with the mob’s ring leaders, according to a documentary about the riots, and about 200 Punjabis — who had been driven out of their homes — spent the night at the police station in the city hall. The following day, the South Asians of Bellingham started heading to the train station, many destined for Canada, and in two days almost all of the town’s estimated 250 South Asians had left the city of 30,000.

Fortunately none of the victims were killed, though many were injured while trying to escape the mob.

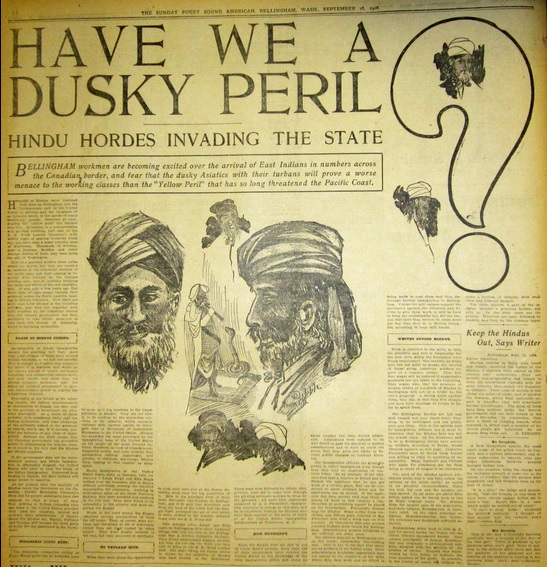

Historical documents about South Asians in the American Northwest during that era, available through SAADA, reveal two themes that are relevant in today’s immigration debate: economic anxiety and fear of an immigrant “takeover.”

The 1906 article “Have We a Dusky Peril?” reports about concerns that South Asian workers, who were being hired due to labor shortages at the lumber mills, would lead to lower wages: “they live cheaply and save their earnings to return to India to spend them.” Similarly, Adolphus W. Mangum, a soil scientist by training who was doing fieldwork in the area, wrote a letter to his mother a few days after the riots saying that South Asians “will work for wages that a white man can’t live on” and that they “can live on ‘nothing per day.’” The Seattle Morning Times said, “When men who require meat to eat and real beds to sleep in are ousted from their employment to make room for vegetarians who can find the bliss of sleep in some filthy corner, it is rather difficult to say at what limit indignation ceases to be righteous.”

Such arguments have parallels today when people say that immigrants are willing to work for lower wages and that they therefore threaten the employment prospects of native-born citizens.

Another parallel is the concern that South Asians would take over the region and overshadow whites. We see a somewhat similar sentiment today when extremists chant, “You will not replace us!” and rage against whites’ declining percentage of the U.S. population.

Consider the following headlines and subheadings from articles published between 1906 and 1908: “Hindu Hordes Invading the State,” “Invasion of Sikhs from the Punjab,” and “The Foreign Invasion of the Northwest.”

While history is repeating itself in some ways, we’re also learning to avoid mistakes of the past. In April of this year, Bellingham installed the Arch of Healing and Reconciliation, a 12-foot-tall monument that memorializes the sacrifices and contributions of all immigrants to the Pacific Northwest since the 1800s. Made from red granite from India, the arch also recognizes ugly aspects of Bellingham’s past: In addition to the 1907 riots, Chinese immigrants were expelled in 1885, and Americans of Japanese heritage were incarcerated in internment camps during World War II. The arch is seen as both a “bridge to the past” and a “monument of hope moving forward.”

Satpal Sidhu, chairman of the arch committee and a member of the Whatcom County Council, said in April, “This is a memorial — a reminder for the next generation. What happened was not right, and it shouldn’t happen again.”

And that’s why we should study the past. While certain circumstances and challenges repeat themselves, how we as humans respond to those circumstances and challenges can change — for the better.

* * *

Preeti Aroon (@pjaroonfp) is a Washington, D.C.–based copy editor at National Geographic and was formerly copy chief at Foreign Policy.