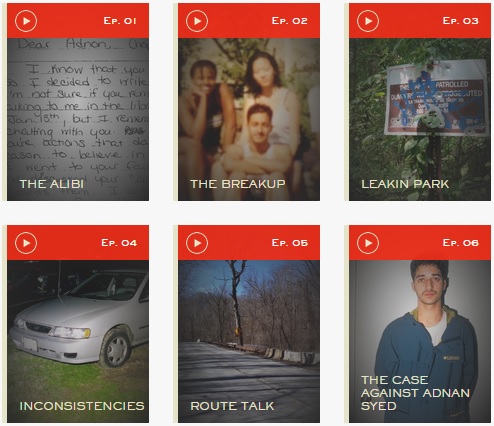

For the past two months, I’ve been quietly tolerating the podcast Serial, Sarah Koenig’s investigation into the 1999 murder of high school senior Hae Min Lee from Woodlawn, Maryland, and her half-assed character study of her convicted-by-law killer, Adnan Syed. I won’t rehash all the details — if you’re reading this, likely you are one of the many who like me, have been feverishly following this story.

But in that time, I’ve been at odds with most friends who I’ve talked to about this, who week-by-week flip-flop over whether they trust Adnan, a Pakistani-American, who so well aligns to both sides of the hyphen. How could such a nice, well-spoken boy be so at peace when speaking from a high-security prison about the murder of his ex-girlfriend?

The entire run of Serial‘s inaugural season has been chasing this one elusive reveal, like some punch line, turning it into a modern, intellectual Law & Order: SVU.

Koenig has missed the point entirely: the mystery isn’t whether Adnan committed the murder; but the lives they lived, the faces they showed to the people around them, and why all of them are in such disconnect over why he could or couldn’t be a murderer in the first place.

The oversight has come under fire before, in articles that accuse Koenig and the show of suffering from a blindness of white privilege and seeing Asians as model minorities, that accuse the show of painting it’s Asian “characters” with broad brushes. But I’d argue in addition to white privilege, Koenig’s bigger fault is quite simply at her job as a journalist — eschewing the human story and instead trying to make a pulp thriller.

In talking to people about Serial, I’ve stressed two points: 1) this murder, heinous and gut-wrenching as it is, is quite normal in Baltimore; and 2) despite Koenig being unable to grasp her own topic, it paints a very familiar painting of what growing up in Baltimore County is like.

Let me make something clear: I’m very biased toward believing Adnan’s innocence. I know Adnan Syed — not personally, but I know exactly where he comes from.

“I know Adnan Syed — not personally, but I know exactly where he comes from.”

I grew up in Reisterstown, Maryland, a couple towns over from Woodlawn, but ultimately it was all one big neighborhood. In my dweeby teen years, interested in video games and Criterion DVDs, the infamous Best Buy at Security Boulevard was a second home. I attended a magnet middle school for math and science a just a few miles from there.

To put it bluntly, I was not Adnan Syed. But in 1999, he sure was the kind of kid I idolized.

Some of the episodes touched on Adnan’s upbringing in the South Asian family, discussing how at home and in his Islamic community he was a “good boy” — he prayed with the family, showed respect to elders, and was genial towards all.

But Koenig has tried hard to draw dissonance between that and the “other” Adnan at school, with his American friends — a kid that partied, smoked pot, had a secret girlfriend.

Many children of immigrants, South Asian or otherwise, know this double life well. The state prosecution, and increasingly the podcast, used this duplicity as proof of Adnan’s guilty character.

Baltimore is a hard-scrabble place: a mostly blue-collar community, one of racially diverse enclaves that brush shoulders and never quite mix. The cast of the show — spirited litigator Rabia Chaudry, skeezy drug dealer Jay, the soft-spoken cops Ritz and MacGillavary — are people who probably wouldn’t come into contact with each other in any other situation.

And yes, murder is fairly common, as shown in Episode 3 “Leakin Park.” Every year around this time, among the holiday cheer, I have vivid memories of the local TV news almost nightly counting down the calendar, wondering if Baltimore’s homicide rate would exceed last year’s, if there were more bodies than 365 days in the year. It’s the twisted game we Baltimoreans play. Sick as it is, how else do you cope with a place nicknamed Bodymore, Murderland?

Shame on Koenig, who was a reporter at the Baltimore Sun, for seemingly forgetting what sandbox she’s playing in. Instead, the deeper she digs the more she’s confounded at the contradictions she finds, unwilling to accept this aspect of Baltimore life.

Children of immigrants are used to compartmentalizing their double lives. It’s too much bother to explain to family or friends; you just don’t cross the streams. You don’t tell your friends what religious traditions keep you from the party, just that you can’t come. You tell your parents that you’re at a “sleepover,” when really you’re at the club all night. Apologies if I’ve outed our secrets, fellow brown young people.

“Apologies if I’ve outed our secrets, fellow brown young people.”

This status quo doesn’t seem to be enough for Koenig. She’s chasing some golden calf that will make the tumblers click and solve something no one could fifteen years ago.

My feeling is that when the final episode debuts this Thursday, she’ll be no further than when she started.

It’s been apparent from the start; there’s very little plotting for a show supposedly echoing classic weekly installment literature. Koenig herself has admitted she just puts each episode together as more material comes in, zipping around from topic to topic: the testimonies, the Asia letter, the floundering Cristina Gutierrez, and the damn payphones. When she runs cold on one trail, she circles back to another, never building an actual narrative. It’s a patchwork of evidence that’s been exhausted to death.

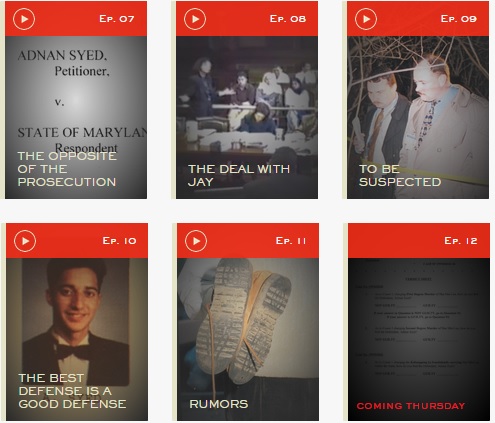

Episode 10, “The Best Defense is a Good Offense,” features Adnan’s grief-stricken mother, still adamant he didn’t do it. You can hear Koenig trying to form a polite question that hid her bafflement over why his mother can’t entertain the possibility that he could do it. But how could she? A world where her son is a killer is alien to her. Adnan knew well enough to hide his school life in the first place.

Koenig snatches at another thread in the next episode — Adnan stole money from the mosque, another sign of his “bad character,” which even the Islamic community shames. But they still pardon him. In their now-iconic prison phone conversations, Koenig suddenly grows apologetic to Adnan about her nosy, rude, accusatory questions (the classic Western politeness of “sorry-I’m-not-sorry”), to which he replies, “If a person can’t figure it out, then it’s not for me to say.”

“Instead, the draw has remained whether or not Adnan is a psychopath.”

It’s a complex situation that is almost inexplicable at times for all children of South Asian immigrants, and ultimately it’s easier to just say, “That’s the way it is.” Don’t say more than you need to, if it keeps the status quo.

So again the question remains, what is it about our society, both for immigrants and homegrown Americans, unwilling to try and figure out this cultural disconnect? Instead, the draw has remained whether or not Adnan is a psychopath.

Is it so hard to think that Adnan was unfortunately caught in a perfect cocktail of societal circumstances that made him an easy scapegoat in a city court that couldn’t reconcile that double life? Why is it so easy to take the virtues everyone keeps praising him of, and bend them as a mask for a violent id?

Maybe the last episode will finally grapple with these points. Maybe Koenig has saved that for her money shot. But I’m not holding out for it.

Aditya Desai is a writer of fiction and essays from Baltimore County, Maryland, now residing in Washington, DC. His writing on the South Asian diaspora has appeared in the Kartika Review and other publications. He received his MFA from the University of Maryland and works for a non-profit teaching creative writing.

Additional reading: Did Serial’s Racialized Archetypes Work Against It?

Sometimes I feel like some writers just latch on to whatever popular thing/notion is going on and write something about it because they know they will get page views or retweets. Unfortunately I think this article counts as one of those times. Exactly what is offensive about Sarah Koening asking Syed’s mother about what she thinks? And personally I’m glad that they discuss the whole dating-is-taboo thing. Most people don’t know about that. I’m glad this experience is making itself known in the mainstream consciousness.

And Koenig repeatedly talks about the high homicide rate in bmore which makes me feel like the writer of this blog didn’t listen to the podcast closely.

What I don’t understand is why South Asian blogs blindly support Mindy Kaling when her show is much more problematic. The LA review wrote a great analysis, but some highlights:

“The Mindy Project is an assimilationist project: Its goal is to place a WOC in the position of a white man, of making her like him…Her character represents a consumerist feminism that is about individual betterment rather than class struggle.”

These are legit issues. The ones raised in this particular article about Serial are reaching.

I disagree with Likewoh’s comment above, the issues Mr. Desai writes about are concerning and deserve to be written about, as demonstrated by the number of other writers who have expressed their own dissatifaction about Ms. Koenig’s representation of the main characters’ racial identities. One point which particularly resonated with me, a child of Indian immigrants who went to undergrad in Baltimore and high school in another Maryland county, is how much of a non-issue to me was Adnan’s “double-life.” As Mr. Desai states, who hasn’t been emergently patched through on a phone call to Puja’s mom to serve as her alibi while Puja is out on a date? And who hasn’t been the one to drive your friends to their dates, so her mom wouldn’t notice a boy picking her up and dropping her off? And etc. Ms. Koenig in her podcast does put a focus on Adnan’s identity, perhaps undeserved–not every American-born child of immigrants necessarily feels such a degree of dissonance between their two identities, does not experience a yawning gulf between the “two sides of the hyphen”-while not acknowledging that her own show also suffers from an identity crisis.

On a first listen to Serial I was very uncritical and caught up in the shallow, gauche “whodunnit”? On a second pass, marathoning up through the penultimate episode, there really is no unifying thread, no underlying current of purpose. The first episode seems to set Sarah Koenig up as plucky journalist ready to go wherever the story takes her, a reporter and detective and essayist. Soon after though, caught up in the very real appeal of Adnan, it seems to shift into a character study…. and soon after that, into a procedural.. and soon after that, into “ruminations on human nature, existenial truths” etc. And the lack of identity to Sarah Koenig’s show I feel contributes to her focus on Adnan’s background–to be honest, the case ended up not nearly as fascinating as it seemed, there was only so many times she could talk about that payphone, or the Nisha call, but she has this show, and it has to be finished, so……

I would however, like to ask Mr. Desai his thoughts on how the show could have been improved then. Should it not have been made in the first place, given the content, the exploitation, the racial implications? Should only a fellow Pakistani-American reporter have followed the story? Should the details about Adnan’s school life vs home life have been entirely cut, and his brown, Muslim identity only mentioned in the one place it must–during the jury’s impression of him?

It’s lazy to say, but it’s almost 2015 and etc, but we’re not in charge of all our own stories, and it’s going to be quite a while until we are.

So, you wanted Koenig to not discuss his background at all? But it’s a part of who he is, and character witnesses would have been important in this trial. I feel like if she didn’t discuss his background, that would be much more problematic on multiple levels. Coincidentally, that’s what bothers me about The Mindy Project, her family and background have been de-emphasized.

I also went to college in Bmore, and I don’t get what your point is that you did. That’s great Adnan’s background isn’t remakable to you. But you’re not the only person listening to the show.

There are much more shallow, gauche things consumed by mainstream media. The show didn’t follow a traditional way of presenting a story, I guess Koenig decided to step outside of what other people learn in journalism school or mfa programs, but whatever it was, it clearly worked, as evidenced by it’s incredible success, that has seemed to have even overshadowed it’s parent program, TAL.

I’m not entirely sure why you’re bringing up Mindy Project again. I go in on defending her but I’m biased because while I don’t think the show is perfect, I am Indian, dark skinned, overweight, and in my 4th year of med school so I relate a bit too much. However, the key difference lies in that TMP is fictional while Serial is true life, and while TMP is problematic for a lot of reasons I don’t see how it’s entirely relevant here.

I did not say that Serial as a whole is shallow and gauche, just that the “whodunnit?” aspect of it is. For all its faults Serial does have layers, and the mystery-solving instinct in us is what drew me in at first. Only after a re-listen did I start appreciating more faults.

My statement about Adnan’s life being so relatable to me was not a judgement on all those who cannot comprehend it, but more so agreeing with a point Mr. Desai made. Why did the racialism of Serial not strike me at first?–possibly because I did fill in the gaps with my own background and did not view the podcast through the lens of a white person.

I also feel that Adnan’s background is relevant to who he is, which is essentially what Serial became: a character study of Adnan Syed. I meant to ask Mr. Desai what he thought might have mitigated the problematic racial aspects of the show.

Just saying, Serial would have been a better podcast in my opinion if it stopped after the episode describing the trial, the jury, the very real flaws in the justice system. Personally I take a dim view on the possibility of the true extinction of racism. I’m more than certain that as politically and socially aware as I attempt to be, many of my statements could be ignorant, malignant, microaggressive, problematic–most of my social theory is informed by the budding anthropologists/social justice warriors on tumblr. In this case I feel it’s inevitable that a lady with centuries of colonialism running through her veins who grew up in an environment priveleged enough that she went to a liberal arts school and pursued journalism necessarily viewed Adnan through a brown lens.

Which is exaclty why I’m very interested to hear Mr. Desai’s thoughts on how the podcast could have been improved, not just from a narrative perspective as discussed, or even debating if it should have been made at all (bc the case wasn’t really that interesting, not after about 6 or 7 episodes), or if it should have been cut shorter than planned despite its phenomenal popularity bc of the above. But how it could have been handled more sensitively. Tbh I’m a person who isn’t educated enough to see subtle racism and microaggressions. To me, when Koenig mentioned that she wasn’t sure what Hae’s diary would be like, just that it’s such a teenage girl’s diary– I didn’t interpret that in a racial way, I thought of it more like: ok, this is a girl who has all this mystery surrounding her, does her diary give clues to being involved with a drug ring, to being eating disordered, to really anything extraordinary or remarkable that you might expect from a movie about a murdered girl. But then again I’m not Korean so I’m really not allowed to have an opinon on that statement, I know.

Just because racialism is (imo) inevitable for now doesn’t mean measures shouldn’t be taken to improve cross-cultural relations especially in the context of recent events.