He narrowed his blindgreen eyes and asked in a slygreen whisper…

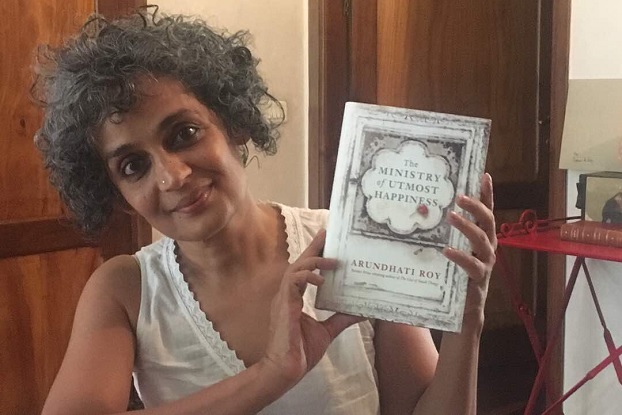

Arundhati Roy’s second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (Knopf), published 20 years after her first beloved debut, The God of Small Things, was perhaps one of the most anticipated novels of 2017. It’s had a mixed reception and I can see why. The novel starts off in old Delhi with Anjum, a hijra, along with a colorful cast of characters. One of my favorite things about the novel is how the city’s flora and fauna is as much a part of the story as the humans.

When the bats leave, the crows come home. Not all the din of their homecoming fills the silence left by the sparrows that have gone missing, and the old white-backed vultures, custodians of the dead for more than a hundred, million years, that have been wiped out.

The old city’s centuries long Muslim culture and architecture is nostalgically laid out, and Roy’s ear for language and detail is often sublime: “a small tortoise…with a sprig of clover in one nostril.”

I found Anjum compelling if tropeful — an elegant fierce outspoken Urdu poetry-quoting drag queen. It wasn’t obvious to me immediately that her companions and antagonists — and pretty much every other character in the book — are also symbols. They represent the many conflicts that routinely tear India apart and that have occupied Roy’s political, human rights, and environmental concerns and her nonfiction writing for the past 20 years: the Hindu-Muslim divide, the caste system, the Kashmir conflict, the Indo-Pak wars, the 1992 Gujarat massacre, the 1984 Bhopal gas leak, and of course the farmers and fishermen whose lands and livelihoods are variously taken over by capitalism and corruption and other horrors.

The second half of the novel turns to the monstrous ongoing civil war tragedy that is Kashmir, following four college friends, a civil servant, a journalist, a Kashmiri activist, and the woman they all love. Again, the tropes and stereotypes abound: the quiet noble freedom fighter, the ambitious journalist, the suave diplomat, the mysterious beautiful woman who doesn’t have to say anything, has no past, but everyone falls anyway.

There was something unleashed about her, something uncalibrated and yet absolutely certain.

Despite this, I was wrecked by the account of the war in Kashmir. There is a scene when a boy is brought in after interrogation (i.e. torture, which is so graphically described at times that I wanted to throw up).

To refuse to show pain was a pact the boy had made with himself. It was a desolate act of defiance that he had conjured up in the teeth of absolute, abject defeat. And that made it majestic. Except that nobody noticed. He stayed very still, a broken bird, half sitting, half lying, propped up on one elbow, his breath shallow, his gaze directed inward, his expression giving nothing away.

Even with the overwriting, the melodrama, I don’t think I’ll ever forget this broken bird of a boy. I didn’t grow up in South Asia, and I’ve never been to Kashmir, but its beauty of landscape and people is legendary. I have long recognized the utter wonder in people’s voices when they speak of the region. And it seems as if there’s no way out now, no light at the end of the bloody tunnel. There are so many militant groups, so many broken families, so many displaced people of different religions, so many armies and guerrilla forces from India and Pakistan, so much sorrow, so much loss. No one wants to let go. No one will and everyone suffers for it. This is not a new story to South Asians (which might explain some of the grim subcontinental reviews of the book), but the novel outlines the longevity, continuity, complexity, and intensity of the conflict, and it is overwhelming and horrifying.

That said, there are entire sections of the novel where semi-journalistic/semi-diary reports of violence, political intrigue, and human rights abuses in Kashmir are clumped together without context or explanation. This is a shame because these are real and important stories, but without tying them to characters we’ve grown to know or the places they inhabit, they end up feeling extraneous. I read these awkwardly written sections impatiently, trying to figure out how they tied in, and when they didn’t, waiting for the book to get back to the story. It felt like lazy writing, or lazy editing perhaps.

The two halves of the novel are tied clumsily together with a plot point — a baby — that appears magical-realism style. Of course, in addition to connecting the two halves, this baby serves its political purpose, standing in for another conflict, this one from the vicious war the Indian government is waging against its own citizens — Maoist guerrillas in the jungle.

Normality in our part of the world is a bit like a boiled egg: its humdrum surface conceals at its heart a yolk of egregious violence.

If you don’t know much about modern Indian history and politics, Roy’s novel is an education, and an indictment of India Shining. Political figures are tarred and feathered, including the current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, referred to as Gujarat ka Lalla. The country-wide violence, corruption, and discrimination seem bone deep, systematic, inevitable. Perhaps it’s as the novel itself says, “There’s too much blood for good literature.”

But I have faith. Maybe now that Roy has painted the broad strokes in her second novel, her third might go more small things than utmost, deeper than wider. However, I have less faith in the future. If history is indeed a revelation of what’s to come as much as it is a study of the past, as The Ministry of Utmost Happiness claims, then “pretending to be hopeful is the only grace we have…”

* * *

Abeer Hoque is a Nigerian born Bangladeshi American writer and photographer. Her memoir Olive Witch (Harper 360) was released earlier this year in the U.S., and The Lovers and the Leavers (HarperCollins India) is her book of interleaved stories, poems, and photographs. See more at olivewitch.com.