The exhibition Coolie Coolie Viens featuring the work of Canadian artist and scholar Andil Gosine, on view at the McIntosh Gallery at Western University until Jan. 12, explores life after indentureship and traverses several mediums including metal, textile and everyday objects. The show reflects Gosine’s history stemming from the “brown sugar diaspora.” This diaspora includes descendants of indentured Indian laborers shipped to sugar plantations in the Caribbean after British slavery ended from approximately 1838 to 1917.

To explore the often unseen histories behind the collective migrations from India to the Caribbean, as well as his own multiple migrations, Gosine turns to local studio photography and the artefact of a studio portrait. (Made in Love) is a video installation (running time 3:23 minutes) built around these images.

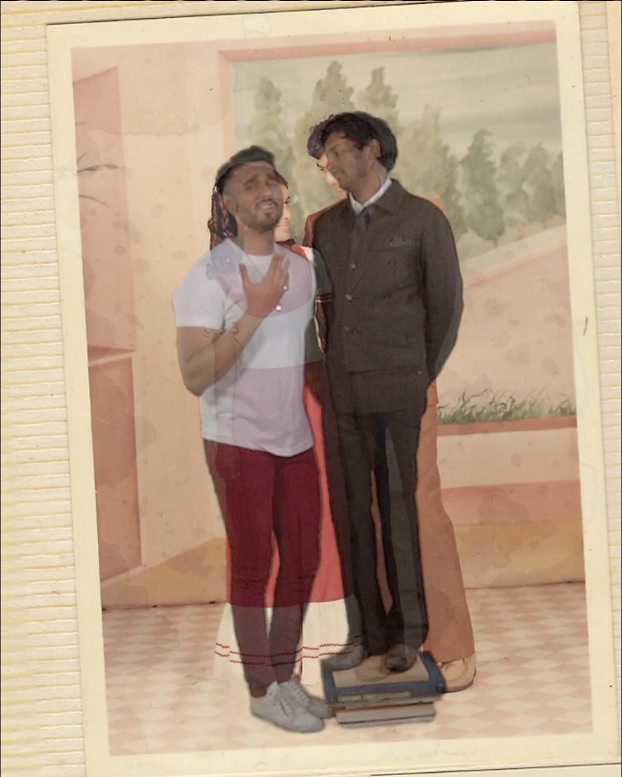

(Made in Love) centres around a studio portrait (circa the 1970s, Trinidad) of Gosine’s youthful parents gazing deeply into each other’s eyes with love and affection. They both have slight smiles suggesting an awareness of their pose and even a sense of playfulness. Gosine digitally superimposes the original photograph over a video of two figures positioned carefully behind the parents, one of whom is Gosine and the other Vivek Shraya, a transgender artist.

The parentheses in the title, (Made in Love), are not merely decorative. Parentheses often mark a digression in thought but here they enclose the title, protective over its departures.

One of the departures could be seen as a challenge to the narrative of the queer experience of being cut off from family, particularly in places labeled uniquely homophobic in the global media (like the Caribbean).

(Made in Love) insists on the presence and survival of entwined emotional histories in Trinidad. Simultaneously, it probes the invisibility of such history and memory, especially as one migrates from south to north.

The video brings together questions of intimate archives and aesthetics, overlapping ideas of remembering and forgetting and inserting queerness into representations of the past.

Passport photos

Local photography in the Caribbean historically consisted of family-run studios rather than any “high art” practice; yet studio photography has become an interesting site for contemporary artists to explore reversions in time or place. Photo studios like Chung’s in San Fernando, Trinidad or Mootoo’s in Rosehall, Guyana, provided wedding and family portraits, or passport and visa photos, thus playing an important role in the stages of community life.

It might be easy to overlook photo studios located “south of the Caroni” or in Berbice (metonyms for Indo-Caribbean locales linked to the sugar industry), but these studio spaces visually crafted representations of self, family and community for those whose lived in close proximity to the cane fields, in the shadow of plantation history.

Studio photos were exhibits of future aspirations (e.g., passport photos for intended migration) or personal mementos celebrating intimate moments. In other words, they were new ways of seeing, and crafting, one’s place in the world. These studio portraits have become aides-mémoire to the past, especially for those outside the Caribbean, becoming in effect a testimony to migrant memories and imagination.

An archive of feelings

A contemporary interpretation of the haunting melody “A Whiter Shade of Pale” is sung sublimely by the figure on the left: Shraya, positioned behind Gosine’s mother. Gosine stands still, behind the father (suggesting a genealogical depth to the video layering). The singer appears more visible due to her gestures which accompany the beat (reminiscent of an electronic tabla), while Gosine is relatively obscured.

Both remain ghostly figures behind the parents until approximately the three-minute mark, when the figures emerge briefly. The singer becomes fleshed out on the sorrowfully rendered lyrics “turn a whiter shade of pale,” only to quickly fade as if an illusion.

The combination of those mournful last notes, and the alliance of brown love (heterosexual/ homosexual/ homosocial) appearing fleetingly on the note of whiteness provokes a visceral reaction in me. This archive of feelings suggests a latent knowledge of “home” for me, one not completely disappeared by migration, but under cover.

According to Freud, “mourning is regularly the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one’s country.” The latter is also suggested in Samuel Selvon’s An Island is a World.

In An Island is a World, Foster, a young Indo-Trinidadian character, wakes up with a lingering dream of migration opportunities spinning in his head. But he soon realizes he cannot belong to that world (i.e., be a cosmopolitan citizen) “because the world won’t have you,” one must “have something to belong to,” and his hopes fade for acceptance anywhere in the world.

Similarly, the pose of the men standing in a similar way, and with similar gazes, as the parents subverts the contexts of family, desire and belonging.

They stand, attendant to gains and losses across migration, love and place. “A Whiter Shade of Pale” scores the video and acts as a siren song of melancholic longing (for loves left or hidden), replacing and shifting the diasporic yearning for home, a shelter made in love.

The hidden layers of the family photo album

Photographs invite new interpretations of family journeys often concealed from conventional discussions of migration. Racialized migrants are limited in representation. The idea of sexual identities rankles mainstream understanding of migrants from the global south.

The brown sugared photo of Gosine’s parents is decidedly distant from cane fields past, moving us into a modern era as an artefact that affirms humanity, not in plantation labor but in love. Simultaneously, it shifts love from the personal and private world to the performative public sphere. In other words, it is a representation of love as empowerment or resistance.

Queered and complicated by the emerging male figures, the video offers a sensory and sensual context missing from the (hetero)normative family photo album. These partially concealed lives provoke a question: what are the hidden layers in the family photo album? Who is hidden from family, from community and history?

By viewing vintage family photographs, imbued with love or desire (thematic elements that also apply conceptually to diaspora), we are reminded that diasporic histories are at once communal, and deeply personal and individual.

The revisiting of these photos is not about nostalgia, but about exploring desires perceptible beneath the surface of communal histories of labor migration. There are, as Gosine’s exhibit shows us, multiple ways to “call desire back to the windowsills of tropical memory.”![]()

* * *

Nalini Mohabir is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment at Concordia University, in Montreal (Quebec). Her teaching and research interests focus on postcolonial and feminist geographies in the Caribbean and its diasporas.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.