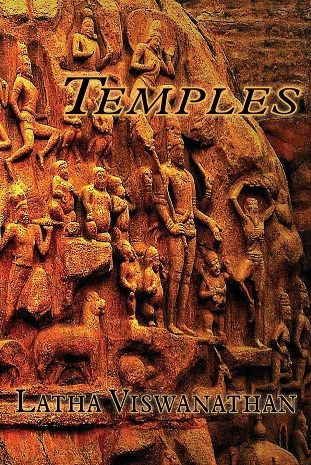

Well, we live in an unjust world — Viswanthan’s still flying under the public radar, despite a slew of awards, including two Pushcart nominations. Her new work, Temples, tells the story of Sathya, an aging archeological curator in Chennai, who finds himself unmoored by the rapidly-changing world around him. Viswanathan is funny, intelligent, and always mercilessly clear-eyed about what’s going on in contemporary India. We discussed her writing, her connection with India, and her ideal reader, all over email.

Q: Tell us about Temples. What did you want to achieve with this novel?

Latha Viswanathan: So many Indians know so much about America. I am not sure the reverse is true. I wanted to write about a changing India where so much is happening, many things relevant to people in America and elsewhere. The issues of toxic dumping, art smuggling etc. — these are things that readers in America need to hear about. I wanted readers to realize that there is a price to be paid for development.

“So many Indians know so much about America. I am not sure the reverse is true.”

So many of us are conscious of climate change but what about the evils of large multinational companies that exploit resources and people wherever they go? Consumption is something that has a cruel side. Indians are embracing this — for the poor Indian, this is dangerous literally. Poor workers in developing countries do not have access to protective gear when they handle toxic substances so sending ships to be dismantled in Mexico or India and dumping batteries and cyber waste in the space of the “other” does not take away our collective global responsibility.

Just because the American or European customer can pay more for art means thieves find ways to give them what they want. It is the worst kind of cultural colonialism that has been going on for a long, long time. The French looted temple pieces from Cambodia and took them back with them. You know what, the Brits did in India. This cannot continue today. We have to stop this kind of looting because someone wants an exotic temple idol in their living room in Manhattan. Of course, there is the other side that is sad here as well — the greed of those engaging in this trade.

As for my main character who is a bit of a curmudgeon, I wanted to portray someone full of contradictions. He is real — we all know this kind of man. He is an intelligent and smart version of an Indian Archie Bunker. Like some diehard younger nationalists, he views immigration as a cop-out. People like him pride themselves on the challenges that India offers as somehow adding to depth of character and identity so immigrants are looked at as fools who chose to jettison a part of their identity. His Indianness is superior, he is privileged and lives a good life. People recognize his importance and admire him. He has a reputation to protect. Why would you toss all this away and start over somewhere far away and leave behind your roots? Like the protagonist, many young people feel the Indian economy is vibrant, their familial and community connections are important. Why leave all that behind?

Q: Temples draws on real-life events and the ongoing social and political changes in India. What sort of distance from facts do you seek to maintain while writing such events into your fiction? And as someone who doesn’t live in India, but writes about it, can you talk a bit about the relationship you have with the country?

“I try hard to avoid the factor of nostalgia creeping in which is sometimes the case with Indians living overseas.”

Just like you, I read the newspapers and keep track of what is happening in India so this is at the back of my head as I write. I try hard to avoid the factor of nostalgia creeping in which is sometimes the case with Indians living overseas. Culture is a living and mutating thing and reflects the reality of the times so I try to mirror that in the plot and character development.

Q: The protagonist Sathya finds himself in a changing India that is destabilizing his hierarchical male Brahminical superiority. Do you see a parallel with the situation in America today?

LV: Absolutely. The prediction of a more diverse and less white America of the future is a source of fear for many. The minority becoming the majority? How can that be? That is not how the country is supposed to be, they claim. This fear and insecurity results in exertion of more control, oppression and this results in more injustice. Look at what’s happening in Texas, in El Paso, at the detention centers. We are in a moral black hole. Take the Me Too movement here and look at the violence against women in India. Poverty and unemployment may be some of the root causes in India — but here in Hollywood, what is the excuse? Greed for power?

Q: Sathya is such a mass of contradictions — capable of such deep insights, and yet, almost comically lacking self-knowledge. I found myself constantly moving from admiration to pity to exasperation and back in response to his behavior. Tell us about inhabiting this character, and understanding how he justifies his attitudes and behavior to himself.

LV: Sathya is human and flawed. Yes, he has great insights but his conditioning, his limited view of the world, the biases he carries deep within reflect such a fractured soul. You know, I know this man well. This was, in many ways, a composite of people I have known. My own grandfathers, who were intelligent and educated but hopelessly bigoted as Brahmin men who thought themselves superior because of the accident of birth. And, of course, that tunnel vision towards Muslims as always being the other, the undesirable. Do you think it ended with that generation? I wish that was true but it is not. There are Indians in America who speak of caste. It is a very sad thing.

Q: One of my favorite aspects of your novel is that thread of humor running through the story. For instance, there’s Sathya greeting a boisterous dog by saying Om Mahadeva, “a mantra that made the dog stop in his tracks. I had discovered that he was peculiarly affected by the prayer; the words made him freeze at a respectable distance from me […]” Tell us how you deploy humor in your writing.

LV: Humor is what makes everything bearable. It makes life, writing, the pain of an unjust world, all of it, a little easier. It’s candy that heals temporarily but it also gives us pause to see that things have an illusory and ephemeral nature to them because they are part of a man-made system. We created the ugliness and then we complain about it. After all, we are all members of the society we complain about. It is also a bit of self-knowledge. An awareness that we too are responsible and we suffer from the same limitations as those we point a finger at. Laughter is healing, a great leveler that shows our common vulnerabilities. Humor cracks the façade and shows what lies underneath — the spirit that stays resilient through all the ups and downs.

Q: You are unapologetic about insider references, expecting the reader do the work to attain understanding. Who is your ideal reader, if any?

LV: My ideal reader is curious and hungry to learn about the world, different cultures and all the diverse people that make up the population of this planet. How fascinating to glimpse into one whose life, surroundings, culture and language are far from one’s own! As a student going to school in India, I never questioned the fact that I had not seen a daffodil and therefore could not relate to the poetry of Wordsworth, or could not understand the society that Austen’s characters lived in. Our humanity binds us all. I believe that a good reader can grasp this.

Look at the books by so many fine writers like Junot Diaz and Adeline Yen Mah. As readers, we need to acknowledge the reality of globalization and the interconnected world we live in. Readers have to learn to walk the world, as they say. And there is always Mr. Google if you need further clarification. We are lucky indeed.

***

Niranjana Iyer is an editor and writer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her website is thecompellingstory.com. Find her on Twitter @ninaiyer.