Welcome back to The Aerogram Book Club, where Book Club editor Neelanjana Banerjee brings together writers and thinkers to discuss South Asian books of significance every other month. Join in with your thoughts in the comments after reading the discussion with Mahmud Rahman, Daisy Rockwell, and Kevin Hyde.

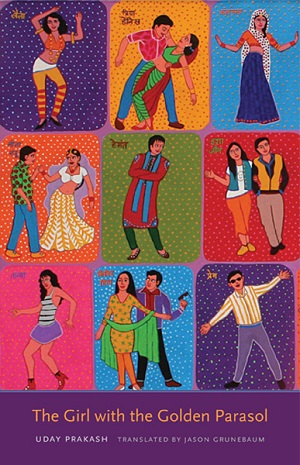

Last year, book club discussant Mahmud Rahman wrote a five-part series for the Asymptote Journal blog investigating the lack of South Asian writing in translation published in America. He wrote that “in the last five years, out of 2121 books [published in translation], only 19 were from South Asian languages (only Urdu, Hindi, Bangla, Tamil).” For this reason, I tapped Rahman to bring together our book club readers this month and choose a translated book that has been published in the United States. Rahman picked Uday Prakash’s The Girl with the Golden Parasol, originally written in Hindi, and published by Yale University Press.

The novel centers around a love story: university student Rahul falls for classmate Anjali, but the caste-system and politics interfere with their romance. Prakash received the Sahitya Akademi literary award in 2010 for his poems, short stories, and novels. He lives in Ghaziabad, India. The Girl with the Golden Parasol was translated by Jason Grunebaum, a senior lecturer in Hindi at the University of Chicago.

– Neelanjana Banerjee

Mahmud Rahman: The Girl with the Golden Parasol is a campus love story interlaced with commentary on larger issues: caste discrimination on the campus, ossification of Hindi literature, thuggery aligned with university administrations, and the fractures within an India undergoing economic liberalization. This is different from most campus novels I am familiar with, those from the U.S. or the U.K. This small genre is often set in university English departments and the characters and drama focus on faculty, academic factionalism, dead marriages, sexual affairs. They are often satirical.

Mahmud Rahman: The Girl with the Golden Parasol is a campus love story interlaced with commentary on larger issues: caste discrimination on the campus, ossification of Hindi literature, thuggery aligned with university administrations, and the fractures within an India undergoing economic liberalization. This is different from most campus novels I am familiar with, those from the U.S. or the U.K. This small genre is often set in university English departments and the characters and drama focus on faculty, academic factionalism, dead marriages, sexual affairs. They are often satirical.

In India too, campus novels have emerged as a small genre. I’ve read one other. These tend to focus on student life and are built with coming of age narratives. There is humor in these novels but it’s more the humor of young people mocking one another’s foibles. Overall, they’re more youthful.

“The Girl with the Golden Parasol is a campus love story interlaced with commentary on larger issues…”

Uday Prakash’s novel has a large dose of satire as well as the humor of the young. It opens with Rahul’s infatuation with Bollywood star Madhuri Dixit. Soon this turns into a crush on the very real-life Anjali Joshi who joins Rahul’s circle of students. Rahul ditches anthropology for Anjali’s Hindi department. They strike up a romance, but it’s fraught with risk: she’s Brahmin, he’s from a lower caste, she is a state Minister’s daughter, and there are government-connected goondas on the loose. Meanwhile, Rahul’s dorm mate, Sapam Tomba, a Manipuri, commits suicide after intolerable harassment. Rahul joins his classmates in a movement against the thuggery and corruption.

Life on this “Cambridge of India” campus sounds similar to Bangladeshi public university campuses I am familiar with. Goondafied administrations, a nexus of political parties and government-appointed bureaucracies, have a long history. The fractures are different. In India, it appears that caste is a dead weight hanging over everything. In Bangladesh, it could be the metropolitan and small town divide, but even more potently these days, which political party one supports.

The book attempts an ambitious mix. The love story sometimes falls into clichés where I wondered if there’s an ironic element that I missed. But I was able to get past that because Rahul’s ideas of romance, perhaps common among his peers, are strongly influenced by the movies. The polemic against caste sometimes verges on repetition. But the mix accumulates into both an enjoyable love story and a sharp commentary on today’s India.

The English that Jason Grunebaum chose in his translation leans towards current American usage and is excellent. Though I’ve read many Indian books in translation, they have mostly been from Bengali. The Girl with the Golden Parasol is one of the few novels from Hindi. When I read a translation from Bengali, a language I know, I often read with a second ear listening to, or wondering about, the Bengali in the background. I do not know Hindi. Reading Uday Prakash’s novel, my second ear couldn’t hear anything.

I’m curious, Daisy, both how you found the novel as well as the translation — since you know and translate from Hindi and may even have read the original work? And Kevin, since you don’t know Indian languages and I’m not sure how much Indian fiction you’ve read, what did you make of the novel and its language?

Kevin Hyde: Hello to you all! Thank you, Mahmud, for getting this started. I found The Girl with the Golden Parasol at once entertaining and clever. I like that Prakash camouflages a pretty withering critique of Indian capitalism (and its attendant corrupting effects) behind both a funny, intense romance and a sort of gang-of-misfits contra mundum adventure.

Kevin Hyde: Hello to you all! Thank you, Mahmud, for getting this started. I found The Girl with the Golden Parasol at once entertaining and clever. I like that Prakash camouflages a pretty withering critique of Indian capitalism (and its attendant corrupting effects) behind both a funny, intense romance and a sort of gang-of-misfits contra mundum adventure.

As you pointed out, Mahmud, it’s unlike most campus novels and it does, somehow, feel younger, probably because it is less concerned with the vicissitudes of put-upon faculty than most other examples of that genre, and I think part of what allows Prakash to deliver the critiques so successfully is the fact that he focuses, for the most part, on the students, their struggles, and their ideas.

So many of Rahul’s discussions with his friends, or even his imaginings (of the porcine, Viagra-gulping Nikhlani figure, for instance, who is the embodiment, in Rahul’s mind, of the grotesque consumption and cronyism that’s permitted and encouraged by modern capitalism in India) express such idealistic thoughts so earnestly that it’s hard to imagine them coming from any one other than a student. And really, that’s perfect. It works.

It would be tough to have these same discussions come from any one other than students, I think, and have it still be as entertaining or compelling. If the book were more overtly political, say, or if Rahul’s thoughts were put instead in the mind of a radical agitator who thought only of revolution, it would come across, I think, as didactic or shrill. As it is, the critical parts of the book sit naturally next to the romantic and more adventurous elements.

“It would be tough to have these same discussions come from any one other than students, I think…”

To pick up on something you mentioned about the romantic parts of the book, Mahmud, and how much the love story sometimes slips into cliché, I noticed that too and wondered whether Prakash was gently satirizing that sort of movie-influenced behavior. Or maybe he was just pointing out how prevalent that behavior is. What you said reminded me of something David Foster Wallace talked about during a taped conversation in Italy in 2006, where he said:

The language of images…completely changes actual lived life. Consider that my grandparents, by the time they got married and kissed, I think they had probably seen maybe 100 kisses. They’d seen people kiss 100 times. My parents, who grew up with mainstream Hollywood cinema, had seen thousands of kisses, by the time they ever kissed. Before I kissed anyone, I had seen tens of thousands of kisses, of people kissing. I know that the first time I kissed, much of my thought was, ‘Am I doing it right? Am I doing it according to how I’ve seen it?’

To me it seemed like Rahul was using what he’d learned from films as a rough guide to his wooing of Anjali since that was the best kind of knowledge he could draw on in that situation — he can’t help but be influenced, in some way, by all the films he’s seen and internalized.

I thought the language of the translation was excellent too. It seemed to me like Grunebaum made some good choices especially with the student characters and the way they spoke to each other. I liked that he kept (or inserted?) some Hindi in the dialogue occasionally and included expressions and phrases that did not align totally with American English idiom (as I think he mentions in his preface).

It was a pleasure to read something that felt so contemporary and vivid — the fiction I’d read before by Indian authors was written in English and had more to do with the past than the present, and I found it was so much easier to get wrapped up in this book than in some others I’d read, maybe because it felt so current.

Daisy Rockwell: Like both of you, I think this novel is fascinating as a campus novel unlike others. To me, it’s one of the only Indian novels I’ve read in Hindi or English that accurately depicts university life (particularly in provincial India) in terms of its ferocious real-life politics. Of course, with its elements of fantasy, it’s funny to say it’s more realistic than other novels, but this is a particular feature of Prakash’s writing, which often pushes absurd realities to the breaking point and finds the fantasy that lurks inside.

Daisy Rockwell: Like both of you, I think this novel is fascinating as a campus novel unlike others. To me, it’s one of the only Indian novels I’ve read in Hindi or English that accurately depicts university life (particularly in provincial India) in terms of its ferocious real-life politics. Of course, with its elements of fantasy, it’s funny to say it’s more realistic than other novels, but this is a particular feature of Prakash’s writing, which often pushes absurd realities to the breaking point and finds the fantasy that lurks inside.

To me, the unrealistic or clichéd elements of the love story are likewise realistic in that they reflect the way Bollywood fantasy inscribes the psyches of young college students in the Hindi-speaking belt in particular (this is not to say that, for example, Hollywood doesn’t have an impact on the way Western students see romance, but that the Bollywood flavor is of a particularly over-the-top and melodramatic varietal).

The translation is of course wonderfully done by Jason Grunebaum and is what makes it possible for readers to actually achieve any closeness to the subject matter, which is otherwise really quite difficult to delve into for anyone not intimately familiar with the setting. One of the things that troubles us, as translators, is how publishers and critics tend to be turned off by South Asian literature that was not originally written in English, because it’s not as readily accessible to readers, both in terms of aesthetics but also in terms of content. I believe that good translations grab the reader by the hand and do their best to help them through the difficult process of entering unfamiliar worlds.

I know that some people find Jason’s use of distinctively American-inflected idioms jarring, especially if they are more familiar with the context of the work and familiar with Subcontinental English. I would argue, though, that his American inflection makes it possible for readers that would otherwise be bewildered by the unfamiliar setting and subject matter to make that leap and enter the world of the text. University politics, caste struggles, and the bewildering world of Hindi literature are not milieux that many outside of even provincial areas of the Subcontinent will find readily accessible.

“Should we translators be creating two distinctly different translations for a Subcontinental audience vs. an international one?”

A related question that is always stirred in my mind from this issue: should we translators be creating two distinctly different translations for a Subcontinental audience vs. an international one? But even that’s a vexed issue, because then we have Suketu Mehta, for example, critiquing a new collection of Manto short stories in English in the New York Times and taking it to task for being ‘over-translated,’ and basically not ‘desi’ enough. If this is the critique one finds in the NYT, where does one draw the line?

MR: I’ve enjoyed this conversation. Thanks to both of you for your insights into the connections between the romance in the novel and the influence of the cinema.

MR: I’ve enjoyed this conversation. Thanks to both of you for your insights into the connections between the romance in the novel and the influence of the cinema.

Kevin, that was a great quote from David Foster Wallace. It looks like we agree that what might appear at first look to be clichéd about the descriptions of the love affair reflects the very real effect of cinema-originated notions of romance among young people. Indeed many romance narratives in various times and places have reflected something similar: people, in real life and in fiction, often get their ideas about love from novels, TV or the movies.

Perhaps one thing that’s striking about this novel is that in this case, we see this behavior through the eyes of a man. Often it is women who are depicted as influenced by romantic notions derived from books or the cinema, Emma from Madame Bovary offering a classical example.

“Given how diverse English is, we have no choice but to constantly think about our intended readers.”

Daisy, I too wonder about the translation issue you raised: “Should we translators be creating two distinctly different translations for a Subcontinental audience vs. an international one?” This is a question only for those of us who translate into English. If we were translating into Japanese or Turkish, languages with no sizeable readership in the subcontinent, we wouldn’t worry about which Turkish or Japanese to choose. Given how diverse English is, we have no choice but to constantly think about our intended readers.

A final thought: it’s been interesting reading and discussing this novel while working on a college campus in the U.S. My mind drifts to imagining a story set within a college facing the crisis that many colleges are going through these days, with politics, both federal and state, having its impact on affordability and learning, and during a time when the country and many campuses are also rocked by the trials of our times: racial and sexual outrages, unending war abroad, the growth of the surveillance state, police brutality, etc. Will we see fiction emerge out of such scenarios that can be enjoyable to read as well as speak to the hard truths of our times?

KH: Thanks to you both for a wonderful conversation. This has been so much fun. I only have a couple brief thoughts, too:

KH: Thanks to you both for a wonderful conversation. This has been so much fun. I only have a couple brief thoughts, too:

Regarding the translation, I thought Daisy’s point about the choices Grunebaum made was right on — that good translations can usher a reader into an unfamiliar world, and that translator-chosen inflections in service to that end are worthwhile. There was a nice essay not too long ago by poet and translator Michael Hofmann where he says something similar, that he wants his translations to “provide an experience” and that he uses “the full range of Englishes” (British, American, Australian, etc.) in order to achieve that aim and deliver something remarkable.

Going into Prakash’s novel, I had no idea what student life was like at universities in India, much less what that life would be like for a character who has fallen in love with someone from a much different caste — although I can sympathize with Rahul and his situation, that world is essentially unknown to me — but I felt, from the beginning of the book, that I was in good hands, so to speak, with this translator and this author, and I think much of that has to do with the choices Grunebaum made in his translation (which also exposed me to many terms I’d never encountered before: “goonda” and “swadeshi” spring immediately to mind, but there were many others. The translation seems like a nice mix of original elements that Grunebaum perhaps chose to let stand alongside some of the American-inflected idioms).

And to follow up on what Mahmud said about possibly seeing fiction emerge from the political and economic turmoil of recent years, I’ll say that I hope we see novels and stories that are at once as politically engaged and as entertaining as The Girl with the Golden Parasol — there should be special praise reserved for authors who are able to so capably marry personal or quotidian stories to larger social concerns.

“I hope we see novels and stories that are at once as politically engaged and as entertaining as The Girl with the Golden Parasol…”

One of the aspects of the book that’s stuck with me is how funny it is too — which is something that you might expect from a campus novel, but maybe not one that’s as political as this one. Rahul is occasionally very self-deprecating and some of O.P.’s dialogue made me laugh out loud. It’s always impressive to read an author who obviously has an urgent message to convey but who also cares a great deal about the joys of narrative, plot, gags, set pieces, etc.

Prakash does well in switching the focus of the story between Rahul and Anjali’s romance, the students’ struggle with the goondas, and Rahul’s fever-dream visions of hellish late-stage capitalism, and I think the political elements of the book resonate more intensely because of that fact.

***

Mahmud Rahman is a writer and translator resident in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is the author of Killing the Water: Stories, published by Penguin India, and the translator of Bangladeshi novelist Mahmudul Haque’s Black Ice, published by HarperCollins India. He can be found at: www.mahmudrahman.com

Kevin Hyde’s work has appeared in Parcel and Big Fiction and online at Asymptote Journal, Gigantic, and McSweeney’s, among other places. He received his MFA from the University of Florida and lives in Oakland, California.

Daisy Rockwell is a writer, painter and translator living in New England. Her new novel, Taste, is available for order. Her previous publications include The Little Book of Terror and Hats and Doctors, translations of Upendranath Ashk’s short stories.

I am a big fan of Uday Prakash, having read most of his fiction in Urdu published in Aaj quarterly, thanks to Ajmal Kamal. I remember really enjoying Peeli Cchattari Waali LaRki.

I would soon like to read the translation as well. I did wonder about the choices of the words Golden and Parasol though. The words ‘golden’ and ‘parasol’ remove the title/entry point from the pedestrian to elegant. Opening of the novel is full of rusty, acidic, and crude fantasy. The first act of violence is committed on an image of fantasy, the poster of Madhuri Dikshat. I also loved the way Mr. Prakash brought in Janoon song as the students song of revolution. It would also be interesting to compare the Hindi with its Urdu version, to see when and where the Urdu version softens the rustic quality of Prakash’s lower end speech.

Thanks to Daisy, Kevin, and Mahmud for the great discussion and conversation!

And thanks for your comments as well, Moazzam. Uday’s very happy about his Urdu translations, and I believe that there are, in fact, two different Urdu translations of this book, neither of which I’ve read. But I, too, would be curious to compare the Hindi, Urdu, and English versions, and others.

As for the title, you’re not the first person to comment on the change. It was first proposed by Uday, and we decided to stick with it, even though in the book itself the parasol is still yellow (though explicitly a very special hue of yellow).

One justification for the change is that the parasol does magical things in the text (metamorphosing from butterfly into parasol and back again), so “golden” seemed warranted. I also think “golden” makes the title work better—in the history of translations, titles are often (and often justifiably) fair game for change. And we went with “parasol” rather than “umbrella” since it seems that the accessory in question is used more as a sun parasol than a rain umbrella.

After reading this discussion, perhaps the distance from “yellow” to “golden” might also represent the space between reality and Rahul’s fantasies?

Thanks, Jason, for your detailed and engaging response. It is heartening to see someone exploring and exposing a particular writer. My memory of reading it in Urdu is faint at the moment, but I was reading Publishers Weekly’s mini review and it mentions the novel’s choppy execution and frequent rants, which I don’t recall. Would you have any comments? Did you ever feel like you wanted to take out sections which wouldn’t work in English? Secondly, any comments on Prakash’s choice of song by the Pakistani ‘sufi’ rock band Junoon?

Thanks again for your time.