There was nothing new for me about leaving Syria; separation has always been the defining condition of my relationship to the country.

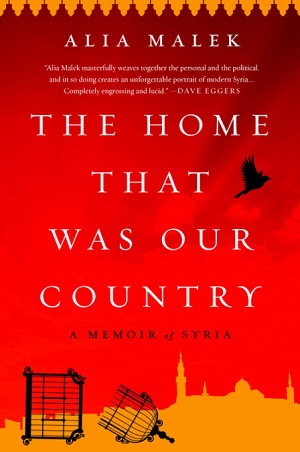

The Home That Was Our Country, releasing in paperback on March 13 from Hachette’s Nation Books, is Alia Malek’s history of Syria intertwined with the history of her own family. Written with a clear-eyed journalistic tone, the story follows the author’s grandmother, Salma, the formidable, charismatic, green-eyed matriarch of a sprawling family. Not unlike the Ottoman Empire of old, many of Malek’s relatives have ties to Palestine, Egypt, Armenia, and Lebanon. And like families all over the world, there are myriad inheritance disputes, both within the family (as per patriarchal structures), and without.

The Home That Was Our Country, releasing in paperback on March 13 from Hachette’s Nation Books, is Alia Malek’s history of Syria intertwined with the history of her own family. Written with a clear-eyed journalistic tone, the story follows the author’s grandmother, Salma, the formidable, charismatic, green-eyed matriarch of a sprawling family. Not unlike the Ottoman Empire of old, many of Malek’s relatives have ties to Palestine, Egypt, Armenia, and Lebanon. And like families all over the world, there are myriad inheritance disputes, both within the family (as per patriarchal structures), and without.

Salma’s flat in Damascus, once the bustling center of Salma’s life is embroiled in a decades long court case with a tenant — one of the ongoing narrative threads as the civil war begins. But it is the seven long years at the end of Salma’s life, during which she suffers a stroke and enters a frozen condition in which she can only move her eyes, that provides the most tragic metaphor for Syria itself.

Malek places blame squarely on the shoulders of Syria’s fascist government regime headed up by the al-Assad family dynasty, which uses propaganda, state controlled media, torture cells embedded within neighborhoods, and the Syrian mukhabarat (the dreaded secret police) to control its population. Age-old feudal systems of landownership and serf-like laborers, as well as the lack of proper infrastructure and progressive economic policies, form the backdrop of discontent that will animate and complicate Syrian politics for generations to come.

Although Greater Syria had significant minority communities — Christians, Ottoman Jews, Shiites, Druze, and Alawites among them — co-existing with the Sunni majority, communal differences in present day Syria are being exploited by various political factions for their own ends, leading to devastating consequences, and what now seems like untenable conditions for peace and stability in the region.

In the heart of the old city of Damascus stands Umayyad Mosque, built on the site of a Christian basilica dedicated to John the Baptist who is honored by both Christians and Muslims. Before the mosque, there was a Greco-Roman temple to Jupiter, and before that, a temple to an Aramaean god. It is this kind of sweeping historical reach interleaved with rich and intimate details of Damascene life that give The Home That Was Our Country weight and depth.

With no stoves in people’s houses (until the 1970s), dishes that needed to be baked (kibbeh, for e.g., ground lamb with bulgur and seasonings) were sent raw to the bakeries to finish them.

The book straddles genres of political history and memoir, but it is Malek’s own story and Salma’s that lifts the narrative above history, as tragic and important as the latter is, as many lessons as it holds for the world today. I found the personal anecdotes most compelling, accomplishing the vital task of making the personal political and the political personal. And who doesn’t enjoy reading about teenage angst, Syrian or otherwise:

My strict Syrian parents didn’t really care about the American teenage experience; nor were they particularly sympathetic to the milestones as they’d come up. I had only gone to a few dances and parties, and only after arduous battles to convince them I would not end up an alcoholic or drug addict.

Malek mourns the terrible irony that Syria has been a centuries old refuge for the displaced, not least among them, the long persecuted Armenians so many of whom have passed through and/or settled in Aleppo. Now that millions of Syrian refugees are being flung across the world, “it seems many Europeans themselves [have] forgotten their own past of devastation and migration.” The Home That Was Our Country is an education, and one that is particularly resonant in today’s world of “expulsion, migration, refuge, and exile.” Would that we learn.

What we were talking about was personal and existential: whether they could belong in their own country…

***

Abeer Hoque is a Nigerian born Bangladeshi American writer and photographer. Her memoir Olive Witch (Harper 360) was released in 2017 in the U.S., and The Lovers and the Leavers (HarperCollins India) is her book of interleaved stories, poems, and photographs. See more at olivewitch.com.

Upcoming Book Event:

“Writing Syria: Alia Malek and Wendy Pearlman in Conversation” Friday, February 23 from 7 PM-9 PM EST, at Judson Memorial Church, NYC.