In the West, “Indian food” for those who did not grow up eating it, either in their own homes or in the homes of friends and family, seems to mean the heavy, rich, dishes that dominate menus in Indian restaurants across the U.S. To the uninitiated, the idea of “Indian Food” often evokes images of buttery, fluffy naan, and rich curries such as chicken tikka masala or paneer makhana — laborious, luxurious dishes that sit heavy in the stomach.

Unfortunately, these images of Indian food that have seeped their way into popular culture do the cuisine a great disservice. Heavy curries, such as those that are favored in restaurants, are not everyday staples of the Indian diet. They may make their way to banquets or weddings or special occasions, but they aren’t the simple, hearty food that exemplifies the cuisine. Furthermore — perhaps more tragically — this standard “set” of typical items paints Indian cuisine in strokes far too broad, ignoring the massive differences between various regional foodways.

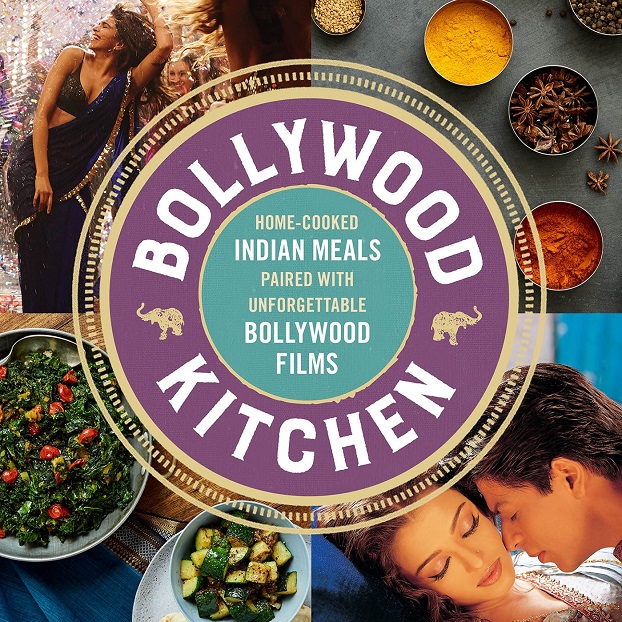

It is for these reasons that a new cookbook called Bollywood Kitchen, by Sri Rao, who has produced Bollywood films such as New York and Badmaa$h Company, is such a joy. Rao is American born, with Telugu roots — and this heritage, as well as his career in Bollywood, both make a strong mark in the book.

Bollywood Kitchen isn’t out to turn anyone into Julia Child, or a Michelin star chef. Instead, recipe by recipe, it shatters myths that those unfamiliar with Desi home cooking may have held — that it is time-consuming to make, requires expensive or inaccessible ingredients, or is too rich to eat every day. It introduces America to the types of balanced, hearty meals that many Indians and perhaps, Indian-Americans as well, eat at home, and proves that if you can chop an onion, you can make Indian food.

“Bollywood Kitchen isn’t out to turn anyone into Julia Child, or a Michelin star chef. Instead, recipe by recipe, it shatters myths that those unfamiliar with Desi home cooking may have held”

Rao’s book opens with a gorgeous introduction to Bollywood film through the ages, complete with glossy stills of scenes from iconic movies such as Devdas and Sholay. For those unfamiliar with the structure and history of popular Hindi cinema, it serves as a cultural primer — explaining why the industry is so beloved in South Asia, and the emotional significance it can have for Desis who emigrated to, or were born in the West. Rao’s introduction is also deeply personal, including photos and anecdotes about his own parents, who settled in Pennsylvania in the early 1980s. The details help get the reader excited about the recipes to come, almost as though Rao has invited them into his home for dinner.

Deviating from the usual format of pages upon pages of recipes, broken down into appetizers, mains, and dessert, Bollywood Kitchen is instead divided into chunks that can be best described as “dinner and a movie.” Each section focuses on a movie that Rao recommends; after a brief introduction to the film and the themes that it explores, he includes three to four recipes which also loosely fall into that theme, to enjoy while watching the movie.

The recipes vary from traditional South Indian (i.e, “Dondakaya” and “Chitrannam”) to more generally Desi-inspired (i.e, “Naan Crisps” and “Bollyburgers.”) Despite the diversity of these recipes, Rao holds true to his promise in the beginning of the book that all the recipes can be made from ingredients easily available to a reader with no access to or familiarity with a Desi grocery store. His recipes are simply, but brightly flavored, with ingredients such as coriander powder, cumin, tamarind, and green chilis. For ingredients the reader may not have access to, such as Indian red chili powder, he provides easily available alternatives.

But of course, the true soul of a cookbook is the recipes, and the dishes that they produce. Therefore, I set about preparing a menu for a few days, using recipes from Bollywood Kitchen. I tried to stay as true to the recipes as possible, without embellishing them at all; however, as a control, I asked my husband, who tends to follow recipes much more rigidly than I do when he cooks, to prepare one dish. Because it wasn’t feasible to prepare each “dinner and a movie” menu in a single evening, and because we cook vegetarian dishes, I chose recipes from throughout the book to test over the course of the week.

“His recipes are simply, but brightly flavored, with ingredients such as coriander powder, cumin, tamarind, and green chilis.”

Butternut Squash Soup & Naan Crisps

On the first night of our test week, I made the butternut squash soup with a side of naan crisps, both from Bollywood Kitchen. For me, butternut squash soup is a labor-intensive undertaking, involving breaking down and roasting an entire butternut squash in the oven. Not so with Rao’s butternut squash soup — he recommends using pre-prepared butternut squash from the grocery store and cooks it directly in the soup, which speeds up the process considerably.

I was skeptical about this lack of roasting — I thought that cooking the squash with dry heat brought out its sweetness — but I found I didn’t miss it at all. The soup was wonderfully spiced with coriander, ginger, and Indian chili powder, and the resulting dish was velvety and satisfying, perfect for a cold day. Although the butternut squash soup was satisfying, the naan crisps were the star of that meal.

Deceptively simple, all they involved was coating store-bought naan pieces with olive oil and a homemade spice blend. The naan was then baked until crispy, forming a sort of chip, the likes of which I have never tasted before. Crunchy, piquant, and warm, these were the perfect accompaniment to the soup — I loved them so much I made them again for company later in the week.

Black-eyed Peas Relish & Chapatis

The dish my husband chose to make was the black-eyed pea relish, which we used as a vegetable to accompany chapatis. Rao suggests it be eaten as a side with a seafood main, or used as the central dish of a vegetarian meal, like we did. It was fairly simple to put together; my husband, who can cook a few staples but isn’t as frequent a cook as I am, found the instructions easy and intuitive.

However, his only gripe was that it seemed to take a few extra steps to get the dish looking like the photo included in the book. The given steps, while easy to understand, didn’t seem to be as detailed as may have been required for a beginner cook. Furthermore, we didn’t find this dish as punchy in flavor as the soup or the naan crisps. It may have been fine as a side, but felt a little underwhelming as a main dish.

For our final meal from the book, I made chitrannam, a lemony rice dish that is made throughout South India, and coconut pachadi, a coconut and yogurt condiment. This was going to be the ultimate test for Bollywood Kitchen — my husband hails from Tamil Nadu, and my family is from Karnataka. These were the dishes we grew up eating, and Rao’s recipes were going head to head with our respective mothers’ cooking.

“These were the dishes we grew up eating, and Rao’s recipes were going head to head with our respective mothers’ cooking.”

Chitrannam & Coconut Pachadi

The chitrannam recipe was straightforward, but upon the first taste, it became clear why even the simplest of South Indian dishes is so much more than the sum of its parts; the combination of toasted red chilies and fried green chilies, along with ginger, mustard seeds, and turmeric, provided an earthy contrast to the sharpness of the lemon.

The coconut pachadi was a bit unconventional; I was confused when I first read the recipe, as it seemed to be a combination of a traditional coconut chutney and a coconut pachadi. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect, or if I would even like the results. However, I was pleasantly surprised. Although it was an unconventional side, I could see myself eating this again with dosas or other rice-based entrees.

In addition to the treasure trove of recipes in Bollywood Kitchen, Rao also provides a primer for South Asian cooking in the last section of the book. These are things that I, and other South Asian cooks, may take for granted — things such as cooking rice, or the different types of breads eaten in South Asian cuisine, or the varieties of daals. But for someone unfamiliar with Desi home cooking, it is valuable. Keeping with his promise to keep his recipes accessible to even the freshest of newcomers to Indian cooking, Rao describes in detail how, when, and why each of these basics are consumed, and how best to prepare them.

For all its inclusion of traditional staples, Bollywood Kitchen is as Indian-American as Rao himself, Desi-fying more American dishes, such as burgers, roast chicken, and cheesecake. It proves it has a place on the bookshelf, whether you’re interested in exploring Indian cooking for the first time, or to freshen up your repertoire.

* * *

Rashmi Venkatesh is a pharmacologist who now works behind a desk and lives in the Metro D.C. area. Her interests include feminism, pop science, South Asian diasporic culture and media, and biryani. You can find her on Twitter at @rashmiv11.