I think you all know by now how big Bollywood is. Not only is the movie industry huge in India, but Bollywood movies are also screened, bought, and viewed in Indian and non-Indian communities all over the world. Even Netflix is exponentially increasing its Bollywood selection to appeal to Western audiences. (For those in the know, I realize that India’s movie industry is diverse and varied and stuffed full of languages and cultures. For the purposes of this article, when I say Bollywood, I mean any movie produced and funded in India, regardless of language. Most of the movies I reference are in Hindi, but some are not. If there are any that I missed, please comment below.)

There are obviously good and bad results of Bollywood fever, like the growing appropriation of South Asian culture in the West and the increasingly sexualized objectification of South Asian women. But I’m not here to talk to you about that. Not today, anyway.

Today I’m here to talk about queer women in Bollywood. Or rather, more precisely, the lack of queer women in Bollywood. (I am talking about queer ciswomen’s representation. Trans* representation in Bollywood is far more popular, but also so, so, so problematic. I will tackle this in a future post. Promise.)

There was Fire, the slow-paced family drama that attracted explosive violence in India. There was Chutney Popcorn, I Can’t Think Straight and The World Unseen. These are all British, American and Canadian films, directed by female directors based in the West and targeted toward primarily English-speaking audiences. The only thing Bollywood about these films is that they feature actresses of South Asian descent. Most of these films were not even screened in India the way that Bollywood films are screened, that is to say, in mainstream theaters to massive audiences in both rural and urban locales.

Queer Bollywood Focused on Gay Men

A few weeks ago, filmmaker Onir wrote on DNA India about the need for more queer cinema in Bollywood. All the examples he uses, however, are male. Maybe it’s the fact that the Bollywood film industry is overwhelmingly male dominated. Or maybe it’s the misogynist and patriarchal elements of Indian culture. Or maybe those two reasons are really just the same thing. Whatever the case, the focus in queer Bollywood has been on gay men.

In 2005, Onir released My Brother… Nikhil, set in the AIDS era about a gay man in India who tests positive for HIV, and the resulting heartache of his life.

Page 3, a mainstream Bollywood film released in the same year, features one of the first explicitly gay male characters in Indian cinema. And when I say “features,” I mean the female protagonist finds out her boyfriend is gay and sleeping with her best friend.

The 2007 film Life in a Metro also has a female character finding out that her love interest is gay.

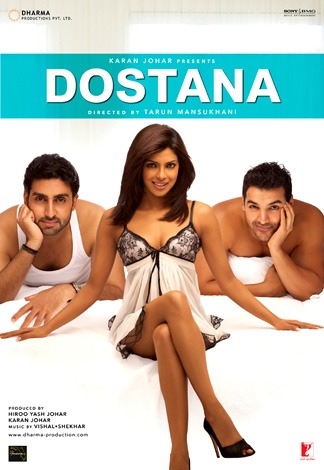

In 2008, the Bollywood box office hit Dostana featured a gay-deception storyline where two straight men pretend to be a couple in order to sublet an apartment with a woman. Both men eventually fall in love with said woman. I Am and Bombay Talkies both tell stories of gay male violence.

That’s six films in seven years dealing with gay men. Mostly the sad, depressing stuff of Well of Loneliness, but also raising important questions about the struggle of gay men. Where are the queer women, you ask?

Queer Women in Bollywood: Tanyas, Tropes & Fantasies

The 1983 film Mandi hinted at a close relationship between the female protagonist, the madam of a brothel, and one of her prostitutes. Razia Sultan, an Urdu film released in the same year, also hinted at a lesbian coupling.

After a long stint of silence on the topic of queer women, Bollywood tried to take on lesbianism in the sensational film Girlfriend, released in 2004. Though controversial, the film passed the Indian Censor Board — perhaps due to its portrayal of lesbianism as male fantasy instead of a legitimate sexuality divorced from the male gaze. The phrase “male gaze” is not enough to accurately describe the thinly veiled lesbian male fantasy of the film. Tanya and Sapna are roommates and old friends from college. They are inseparable until Tanya leaves town for work. The male hero Rahul pursues Sapna and the two fall in love. Tanya returns, and jealous lesbian rage ensues as she tries to get Sapna back from Rahul’s hetero clutches. Not only does the film cast childhood sexual abuse as a cause for lesbianism, but it also features a delightfully psychotic killer “butch” who is obsessed with her object of affection. Add in the made-for-men raunch and you get a flop of a film that garnered criticism for its portrayal of lesbians.

Another iffy attempt at portraying lesbianism head on, the 2006 release Men Not Allowed features protagonists Tanya and Urmila, both of whom are fed up with men. Tanya is an advertising exec from a wealthy family. Tanya’s lesbianism is attributed to her disillusionment with the womanizing men around her (her father and boyfriend). Urmila is a model who is assigned to Tanya’s ad agency. Her lesbianism is attributed to repeated childhood sexual trauma perpetrated by an uncle (who she lived with after her drug-dealer father and addict mother die), and later by men at the orphanage that takes her in. The two become lovers and raunchy skin scenes ensue for the delight of the male audience.

The 2011 thriller Shaitan featured an on-screen lesbian kiss between two of its leading ladies, one of whom is again named Tanya (don’t ask, because I don’t know). The murder film Monica, released in the same year, has homosexual overtones surrounding the female protagonist and subject.

After the flop of Girlfriend and Men Not Allowed, the next film to explicitly tackle lesbian relationships came in 2012. 3 Kanya, a.k.a. Teen Kanya, is a Bengali psychological thriller that shows a lesbian flirtation (sort of) between two of its three female protagonists. It has the potential for a solid film, and none of the characters is named Tanya. Unfortunately, the plot line spins out of control, and the lesbian angle comes off as a sloppy attempt at sensationalism, or maybe just at making the story make sense, which it doesn’t. One of the women in the lesbian coupling has some sort of dissociative disorder (portrayed in a clichéd, non-nuanced way), and ends up killing a bunch of people. The other half of the couple, an officer in the Indian Police Service, is super-glam to a point of unbelievability.

Bollywood is known for being a little campy and kitschy, though often non-ironically. These are all reasons why we love the genre. Not to mention the songs, the exotic costumes, and the dance sequences that are now taught to white people in absurdly expensive classes at local yoga studios everywhere. But when it comes to queerness, and queer women in particular, the male-dominated industry sweeps aside the real stories of queer women in favor of sensational lesbian male fantasies and 1950s-lesbian-pulp-fiction-esque tropes of psychotic murderers and sexually traumatized queer roots.

We can do better than this

One of the critiques leveled at calls for better portrayals of queer people in Indian film is the idea that queerness is a Western invention. While queerness has a recorded and folk history in South Asia, history and culture taught in schools is washed clean of all queer content thanks to the British colonialist values that founded and continue to guide most of India’s education system. For more information, check out Giti Thandi’s Sakhiyani: Lesbian Desire in Ancient and Modern India.

We can do better than this. I love Bollywood (or at least, I used to love it) too much to accept that this is as good as it gets. After India’s landmark 2009 decision to decriminalize homosexuality under its Section 377 Penal Code, the Indian Censor Board has less legal backing to shoot down queer stories. Queer rights visibility is on the rise in South Asia. The time is ripe for some fresh, realistic portrayals of queerness in Bollywood. And while we have plenty of men in the business to give some better perspective and humanization to gay men, getting more women into Bollywood (especially into non-acting roles) is an essential step in better lesbian representation.

This article originally appeared on Autostraddle.

SJ Sindu is a writer and activist who focuses on traditionally silenced voices — the immigrant, the poor, the queer, the female-bodied, the non-Christian, the non-white. Sindu has an M.A. in English from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, with a specialization in creative writing and a minor in women’s and gender studies. Currently Sindu is seeking representation for a novel about a Sri Lankan American lesbian in a marriage of convenience.

Thanks for this article! Now I have more movies to add to my never-ending Netflix queue…

I think “queer overtones” are just about all Bollywood can really handle at the moment without getting too campy. It reminds me of the time when the camera would always turn away as the hetero couple was about to kiss. It seems like it’s only a matter of time before new movies show the struggles of queer love realistically. We *can* do better than this.

I have been long wondering where are my fellow lesbian fans of Indian films, myself! Perhaps if there were more movies telling our(*) stories…

Another film that deals with male homosexuality – and actually in a pretty sweet and sympathetic way – is Honeymoon Travels Pvt. Ltd.

(*) “Our” meaning queer and female; although I am a lover of Indian cinema I am not desi and don’t lay claim to any uniquely desi queer experiences.