Ritu Khanduri is an anthropologist at the University of Texas-Arlington who has been working on India’s cartoon culture for many years. In Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World, we can see the fruits of that work; she has interviewed many of India’s most prominent cartoonists, and has done exhaustive archival research on the earlier generation of cartoonists who are no longer around to be interviewed. She has substantial chapters on early Indian newspaper cartoonists like Shankar and Kutty, as well as the ubiquitous R.K. Laxman (whom she interviewed more than once). There are also chapters on topics like women cartoonists and vernacular language cartoonists.

Ritu Khanduri is an anthropologist at the University of Texas-Arlington who has been working on India’s cartoon culture for many years. In Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World, we can see the fruits of that work; she has interviewed many of India’s most prominent cartoonists, and has done exhaustive archival research on the earlier generation of cartoonists who are no longer around to be interviewed. She has substantial chapters on early Indian newspaper cartoonists like Shankar and Kutty, as well as the ubiquitous R.K. Laxman (whom she interviewed more than once). There are also chapters on topics like women cartoonists and vernacular language cartoonists.

To be clear, the main focus in this book is on what might be called editorial cartoons — the single frame cartoons that appear on the editorial pages of newspapers, not the rapidly growing cottage industry of Indian graphic novels and comic books.

While print newspaper subscriptions have declined precipitously in the west in recent years — and with them the tradition of editorial cartooning has declined as well — print newspapers remain fairly ubiquitous in India, and editorial cartoons remain important. Moreover, because of intense global debates about religious imagery in cartoons (both in the Danish cartoon controversy in 2006 and then again recently with the attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris), it could be argued that we continue to be embroiled in wide-ranging debates about what cartoons are and the role that humor through caricature can serve in a democratic society. Though Khanduri’s book went to print before the Charlie Hebdo event, she does give an account of the way in which cartoonists in India — particularly Muslim cartoonists — understood the debates that followed the publication of a caricature of the Prophet Muhammad in a Danish newspaper.

The pattern of cartoon culture in India follows the general arc of the advent of Indian print culture in general: western genres such as the daily newspaper and the novel were introduced by the British in the 19th century, but over time a growing number of Indians began to inhabit those forms. The first cartoons related to India were produced by the British and represented a British colonial point of view. (One of the most famous is a racially-charged Mutiny era cartoon in Punch that Khanduri discusses in her introduction: “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger”)  By the early 20th century, a large number of indigenous Indian daily newspapers had emerged, both in English and in numerous Indian languages — and with them had emerged a small but important group of Indian cartoonists. Copying the British Punch was an Indian version called Hindi Punch, which intrigued and amused both Indian and British readers (as Khanduri points out, Charles Dickens took an interest in the Indian imitations of Punch, and wrote about them in an essay in 1862 (“Punch in India”).

By the early 20th century, a large number of indigenous Indian daily newspapers had emerged, both in English and in numerous Indian languages — and with them had emerged a small but important group of Indian cartoonists. Copying the British Punch was an Indian version called Hindi Punch, which intrigued and amused both Indian and British readers (as Khanduri points out, Charles Dickens took an interest in the Indian imitations of Punch, and wrote about them in an essay in 1862 (“Punch in India”).

Beginning in the 1930s, a series of important cartoon auteurs would begin to emerge in India, generally identifiable by only a single name (Shankar, Kutty, Bireshwar, Laxman…). The first really important name might be that of Shankar (K. Shankar Pillai, b. 1902 d. 1989). Shankar became influential during the anti-colonial movement, and frequently caricatured the nationalist leaders in the Congress as well as the Muslim League. As Khanduri shows, those leaders were avid consumers of Shankar’s work — and frequently wrote him letters either to protest against caricatures they found to be unfair, or to appreciate a particularly fine or insightful cartoon. Nehru in particular appreciated his importance, and famously wrote him a letter indicating as much: “Don’t spare me, Shankar.”

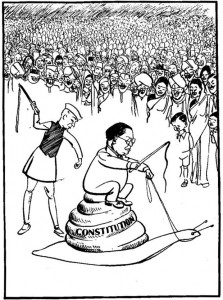

One of Shankar’s cartoons from 1949 — during the complex and sometimes anguished debates over the Indian constitution as it was then being slowly drafted — was recently rendered controversial when it was reprinted in a high school textbook at the national level.

The debate over the meaning of the cartoon seems legitimate — it seems fair to wonder whether, because of Ambedkar’s Dalit background, an image of a high caste man standing behind him with a whip suggests a continuation of caste violence. On the other hand, in 1949, Ambedkar was a powerful and influential figure who could hold his own in the national political landscape; even the way he is figured in Shankar’s cartoon suggests that connection to power. The whip then could also be read as an innocent cartoonist’s shorthand: hurry up, Ambedkar; get the job done.

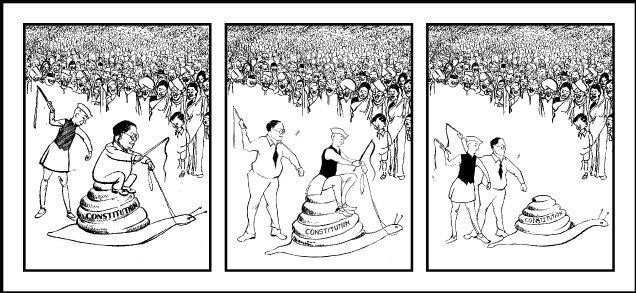

The predictable response to a cartoon like this might be to simply remove it from the textbook and ban it. To my eye, a more interesting response was chosen by a contemporary cartoonist named Makarand Sathe, who reversed the power dynamics in the following reworking:

This more complex handling of the subject finds a way of pushing back against something a little disturbing in Shankar’s original 1949 image, and instead points to the fruitful tensions — and sometimes, shared frustration — of Ambedkar and Nehru in the early years of the Indian republic. (The artist who reworked this cartoon in 2012 published an interesting essay analyzing both the original cartoon and his own version at The Hindu.)

Let’s jump ahead to the figure who might be the most important political cartoonist in post-independence history, Laxman. One fellow cartoonist appreciatively described him as the “Amitabh Bachchan of cartooning”; another, expressing impatience at his incredible longevity,  complained that by the early 2000s, Laxman’s style had grown tired perhaps he was the “Lata Mangeshkar of cartooning” [i.e., someone who had been too dominant for too long…].

complained that by the early 2000s, Laxman’s style had grown tired perhaps he was the “Lata Mangeshkar of cartooning” [i.e., someone who had been too dominant for too long…].

Laxman’s most influential figure was not a caricature of particular political figures (indeed, we would probably not recognize the physical attributes of many of those earlier figures today in any case). Rather, the image that he is most known for today is the “Common Man” — a figure he frequently inserted into his cartoons to suggest the Indian everyman.

Laxman’s Common Man wears a traditional kurta pajama rather than a suit, and a wool jacket. He is balding, with a mustache. And perhaps most significantly, he carries a stick with a small bag of personal possessions that suggests the famous tramp of Sri 420.

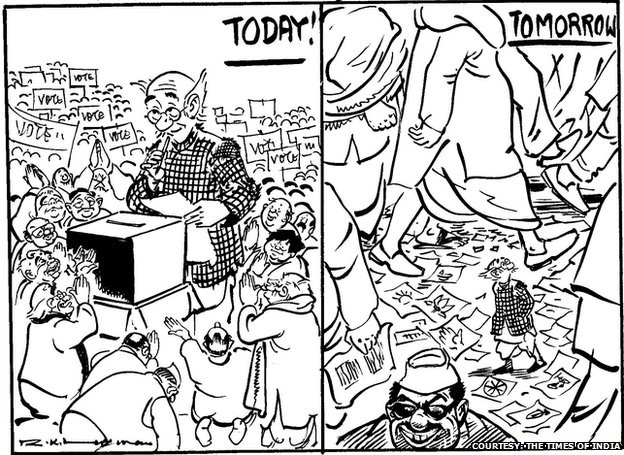

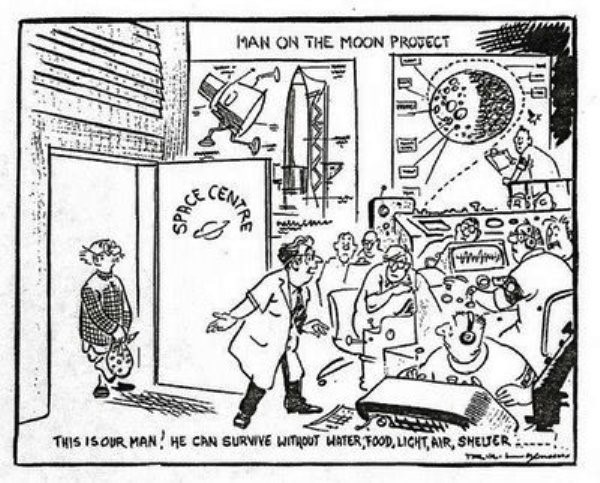

A couple of particularly powerful examples of the Common Man cartoon in action might be these two:

The first image mocks the intense interest of politicians in connecting with ordinary people in the build-up to elections, followed by complete disregard and contempt afterwards. The second points to the discrepancy between the conditions of everyday people in India and the aims and agendas of its most forward-thinking planners: the Indian space agency can be contemplating sending missions to Mars or the Moon, while large swaths of the population lack access to “water, food, light, air,shelter…”

The first image mocks the intense interest of politicians in connecting with ordinary people in the build-up to elections, followed by complete disregard and contempt afterwards. The second points to the discrepancy between the conditions of everyday people in India and the aims and agendas of its most forward-thinking planners: the Indian space agency can be contemplating sending missions to Mars or the Moon, while large swaths of the population lack access to “water, food, light, air,shelter…”

On the whole, Khanduri’s book should be satisfying for readers interested in learning more about the history of Indian cartooning, particularly in its early phases. This particular reader wanted to see more examples of important cartoons, especially given how prolific figures like Shankar and Laxman appear to have been. But Khanduri’s method is more to unpack the culture of cartooning — with an emphasis on the beliefs and practices of the community of cartoonists and their readers; this book does not aim to be a definitive account of any one particular cartoonist’s contributions to the Indian political conversation.

* * *

Amardeep Singh teaches literature at Lehigh University. You can find him on Twitter or on his personal blog.