Ayya‘s Accounts: A Ledger of Hope in Modern India, explores the life of an ordinary man — orphan, refugee, shopkeeper, and grandfather — during a century of tremendous hope and upheaval. Born in colonial India into a despised caste of former tree climbers, Ayya lost his mother as a child and came of age in a small town in lowland Burma. Forced to flee at the outbreak of World War II, he made a treacherous 1,700-mile journey by foot, boat, bullock cart, and rail back to southern India. Becoming a successful fruit merchant, Ayya educated and eventually settled many of his descendants in the United States. Luck, nerve, subterfuge, and sorrow all have their place along the precarious route of his advancement. Emerging out of tales told to his American grandson, Ayya’s Accounts embodies a simple faith — that the story of a place as large and complex as modern India can be told through the life of a single individual. Amardeep Singh reviewed the book on The Aerogram.

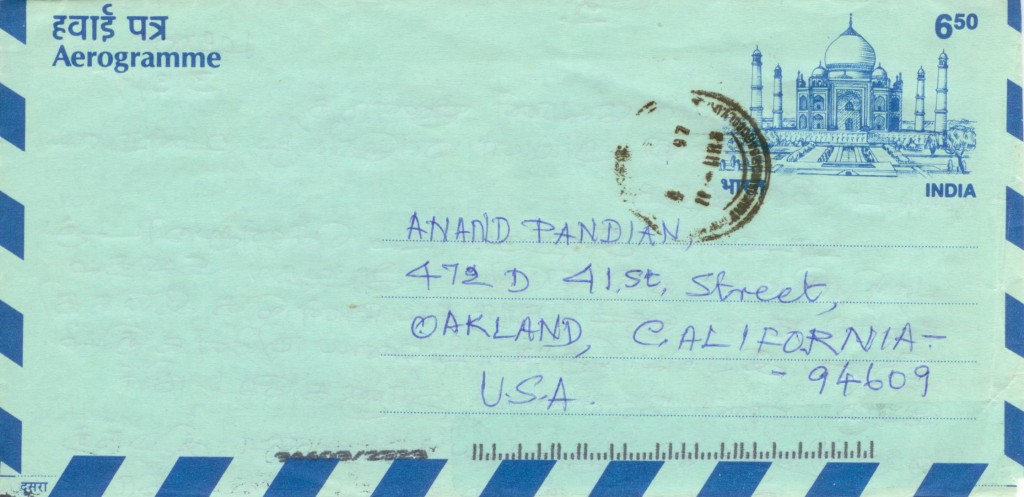

With permission The Aerogram excerpts chapter 23. The chapter was formed around an aerogram from his grandfather, pictured below.

* * *

OAKLAND, 1997

There is so much that my grandmother could have said and done to enrich this book, were she still here. It would have been hers, just as much as Ayya’s. Paati’s powers of description were extraordinary. Even a simple complaint about medicine could swell into an extravagant picture of tablets slipping down the gullet like grains of rice.

The tartness of Paati’s humor cut every unexpected situation down to a manageable size. Once, at an Italian restaurant in Hawaii, she dangled the word “fettuccine” over and over across her tongue, marveling in Tamil at the absurdity of its sound and its dubious appeal. She much preferred the tamarind rice that my mother would box up especially for her.

A sense of numbness was with me still when I wrote a letter to Ayya a few days after her death. That letter is gone, but I have what he wrote back, an aerogram packed with the erratic loops and curves of his Tamil script.

March 3, 1997

To my loving grandson Anand Pandian, this is your Ayya writing. I received your letter.

I’m a little better, now that I’ve seen the encouraging letter that you wrote about Paati having gone to God. Even now, when I think of Paati, tears come unbidden to my eyes. I cried when my father died. In the 63 years since his time had come, only now do my eyes flood by themselves like this. This too will stop in a few days, I think.

I’ve lived with Paati for 55 years. When the time to go your own way comes, there is nothing to do but pull away. What is there to do? In the last two years of her life, Paati suffered deeply because of her illness. Still, she remained very fond of all of her children, grandsons, and granddaughters.

As doctors, your father and uncle looked after her very well. Even if she’d lived a little longer, she would have felt a lot of pain and hurt because of her sickness. In her final moments, her life pulled away without Paati suffering too much. Even she didn’t know that she would go to God so quickly.

In the last hour of her life, myself, your aunt Meena, Murugesan, and Kanna were there with her. We are praying and placing flowers on her photograph and ashes, thinking of her as with us still at home in Madurai.

I heard that you’re coming to India in June. Karthik will come in the month of July. Your uncle Gnanam and his family, and your aunt Raji, uncle Annadurai and Ramesh are also coming in July. We will go to the sea to leave her ashes in the water and pray.

Your aunt Meena, Vignesh, Siva, and everyone else are well. How are you? Don’t worry that Paati is no longer with us. Study well. Karthik and Vidhya also spoke with me on the phone. They told me not to worry, and said comforting things.

I’ve lived in this world now for 77 years. I haven’t suffered very much in these days of my life. But I’ve toiled a lot. What I want is for my children, grandsons, and granddaughters to live by my principles.

Your loving Ayya, MPM

What my grandfather wrote on the death of his wife — something in me wants to leave these words to themselves, as though they say whatever need be said about this time of deepest sorrow. Making an example of them now, as I have been doing with his life throughout this book, seems like an especially lousy thing to do.

But then I read, once again, how he draws this letter to a close. Ayya has already put his own life forward, at this most difficult moment, as an example for others to follow. Out of fairness, then, to this gesture, let me try to tell you what I think it meant.

“What is there to do?” Ayya asks. All of us face entanglements with fate. But they have an especially harsh charge in modern India, where backwardness has long been scorned by observers and critics as the consequence of a passive fatalism.

“Study well,” Ayya also says. We live, with him, in a time that leads us to look resolutely ahead to the future. But there are also certain moments that remind us that the promise of this future is destined to fall beyond our reach. How to reconcile the pull of our ambitions with our knowledge of their limited horizons? What is there to do?

Ayya is an avowed atheist and zealous opponent of ritual customs and religious observances. He is inspired, in this, by one of the most ardent social critics that India has produced: E. V. Ramasamy or “Periyar,” founder of the Tamil Self-Respect Movement in the early twentieth century. Ayya himself has sons in America, doctors whose medical techniques are designed to wage an unyielding war against any indication of the body’s fate. What then do we make of my grandfather’s invocation of God, twice in this brief letter?

Perhaps this is a moment of moral weakness. But I am inclined to give Ayya — and all those, in fact, who appeal in such circumstances to gods or fate — more credit than this, even if my grandfather himself was unwilling to do so. I never thought to try to learn anything from Paati, while I still had the chance, about her practices of religious devotion. But I would guess that God, for Ayya, is a name for chance, for the essential volatility of life, which always moves like the seas into which he was hoping to scatter my grandmother’s ashes.

Indian moral and spiritual lives often seem otherworldly, committed most deeply to possibilities that lie far beyond the world at hand. But this is not where Ayya looks in this letter, as he confronts the death of his wife and the twilight of his own existence.

Life in the world is precarious and chancy. For my grandfather, though, there is nowhere else to look, nothing better than this. To struggle with hope, even in the absence of an assured return, even in the face of so much failure — such is the impulse for progress that he came to share, along with so many others in the world around him. I think my grandmother shared it too.

Anand Pandian is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. He is author of Crooked Stalks: Cultivating Virtue in South India and co-editor of Ethical Life in South Asia (IUP, 2011).

M. P. Mariappan is a retired fruit merchant living in the south Indian city of Madurai.