I was 11 years old when I completed what my family describes as the “thread ceremony.” It took place in our ancestral village in West Bengal. Alongside my cousin who was also made to participate, I sat in complete silence as a priest recited passages from a book.

Our heads had been shaved and I was told to wear a thread, to keep it slung across my chest. This thread, my family explained, was “sacred.” It marked my transformation into a Brahmin man.

By the time we returned to the U.S., I had already lost my thread and over time, the memories receded. However, they reemerged once Narendra Modi was elected Prime Minister in 2014 and again, after Donald Trump became President a couple of years later.

“When Modi won, I remember driving with friends through the South Asian neighborhoods in Jersey City, past the BJP stickers and flags plastered on every window.”

Trump’s election has made me reflect on my own privileges as a middle class non-black POC. I’ve experienced racism but strive to keep in mind that Trump’s rise to power was built on anti-blackness and anti-Muslim/anti-Mexican bigotry.

Similarly, I’ve begun to comprehend how Modi’s policies thrive on prejudices and biases I’ve witnessed even among my own family and others I’ve known in New Jersey.

Yet, a part of me remains unsettled. And after the latest lynching of a Dalit man in India, I must ask: Is it possible to be Hindu and to also champion social justice? By being one, am I not reinforcing a system structured to divide and harm?

I often ask these questions while alone. It usually is silent, staring. Aware that I’m hoping for an answer I can readily accept.

Fascists & Fascism

When Modi won, I remember driving with friends through the South Asian neighborhoods in Jersey City, past the BJP stickers and flags plastered on every window.

What was most disturbing was seeing people I knew celebrate Modi’s victory. These were people who supported my own fight for social justice and who claimed to understand the threat of white supremacy in the U.S.

Yet, none of them seemed to recognize the dissonance between claiming equal rights and equal treatment in the U.S. while supporting a politician like Modi, whose policies attack the poor, Muslims, and Dalit Indians. In fact, the language they would use to defend Modi was eerily similar to what most White Americans say when expressing support for Trump.

“Brahmins are the real victims of prejudice nowadays,” has become a common refrain. “Modi will make India proud again,” they say.

B.R. Ambedkar, the father of India’s constitution and a legendary Dalit revolutionary, warned that Brahmin Hindus can never be reliable partners in fighting for positive change. As long as someone identifies as Brahmin, they remain invested in a hierarchy that places them at the very top.

“In my judgement, it is useless to make a distinction between the secular Brahmins and priestly Brahmins,” Ambedkar stated in his undelivered speech Annihilation of Caste, adding, “They are two arms of the same body, and one is bound to fight for the existence of the other.”

Unlike Gandhi, Ambedkar understood that Hinduism, even when practiced by so-called moderates, is inherently intertwined with caste and hierarchy.

“This is a strategy meant to make the Dalit an Other. It echoes the black-white binary in the U.S.”

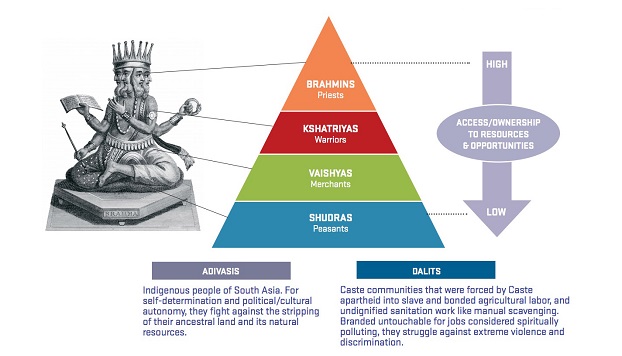

According to Ambedkar, Hinduism is stitched together by rules that privilege certain castes over others. More importantly, Brahmins structured Hinduism to preserve their power by propagating the caste-system, which teaches that people’s place in society is not determined by their actions but by their ancestry. So, if your great-great-great-great-great grandfather was a Brahmin, so are you. However, if your ancestors were Dalit (formerly known as “untouchables”), and therefore at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, then you are a Dalit as well and can never move up.

Essentially, Brahmins, who are the “priestly” caste, devised a system to justify why they should always stay at the top by convincing others that the caste system is religiously ordained. Further, Brahmins sought to divert everyone else’s hatred and disgust to those who are Dalit. Thus, Brahmins perpetuate the myths that Dalits are “impure” and do not deserve the same access to water, food and land that others have.

This is a strategy meant to make the Dalit an Other. It echoes the black-white binary in the U.S., where white elites acquire social power by convincing most white Americans to unite against African Americans.

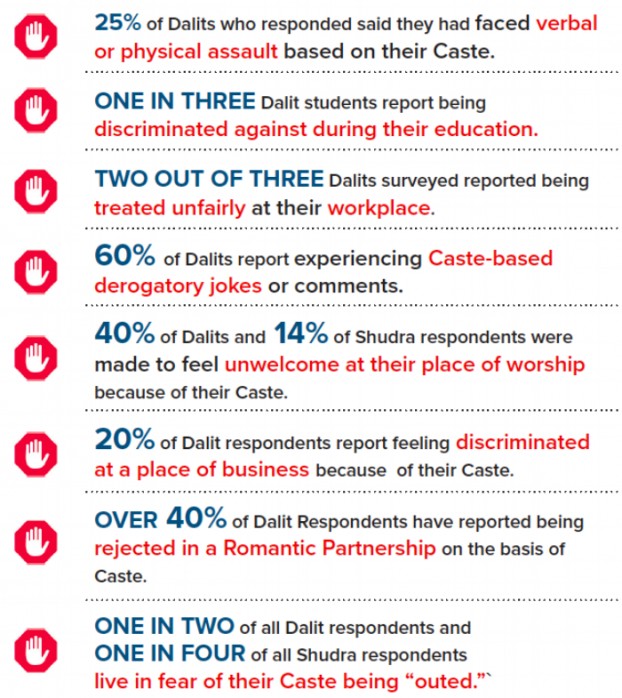

Since Ambedkar’s death shortly after India’s independence, caste is still entrenched in Hinduism and has permeated the South Asian diaspora. According to Equality Labs’ 2018 survey of caste in the U.S., 25 percent of Dalits reported experiencing verbal or physical abuse and 40 percent said they felt “unwelcome” at places of worship.

Ultimately, Ambedkar called for Hindu texts like the Vedas to be discarded. To him, the Vedas and similar texts serve the interests of Brahmins.

“But whether the doing of the deed takes time or whether it can be done quickly, you must not forget that if you wish to bring about a breach in the system, then you have got to apply the dynamite to the Vedas and the shastras, which deny any part to reason; to the Vedas and shastras, which deny any part to morality,” Ambedkar explained, “You must destroy the religion of the shrutis and the smritis. Nothing else will avail. This is my considered view of the matter.”

It Is A Part

At the temple, flowers were distributed among worshipers while the drummer played. My parents were in the crowd as I arrived late and hovered at the door.

I wanted to take a step forward but my gaze remained focused on the priest atop the stage. He was reciting passages. And so, I stepped back into the cold.

“I don’t know what I am doing,” I admitted as I drove to a nearby Dunkin.

It (my conscience, my aspirations, the person I want to be) stayed quiet in the passenger seat.

I sighed and ordered some coffee from the drive-thru and kept driving. Shopping malls and gas stations hurtled past. The night sky was purple.

“I’m not going back to temple,” I said, “I know it’s wrong to be in a place like that now. I know that now…”

It has my face. The clothes that I’m wearing. The same awkward haircut. It, however, is calm, assured, knows something that I don’t.

“Can you please say something?”

What do you want me to say?

I paused. “What am I supposed to do?” I asked.

Eyes rolled. It resumed looking out the window.

A month later, family and friends gathered at our home for dinner. After eating, they complained about those “conspiring” against Modi. I took several deep breaths as the conversation persisted. Finally, I blurted out, “Modi is scum.”

They all turned to me and we shouted at one another until I escaped to a room upstairs.

“I informed my parents that if I have kids, none of them will do the thread ceremony, no matter what family members say.”

It’s already in a chair, flipping through a magazine.

I glared and opened up my laptop and pretended to work until everyone left.

“What am I even doing?” I finally muttered.

It flipped to another page. I raised my voice. “Why aren’t you helping me?”

It flipped again and again. And again.

Another gathering. Another argument ensued. Brahminism is fascism, I told them before eating in another room.

“What am I supposed to do?” I exclaimed once upstairs and the neighborhood was still.

Its eyes were shut. Head down to the wall.

“Whatever, I guess I’ll just keep getting yelled at forever.”

It suddenly got up. Its eyebrows narrowed.

A man was lynched in Gujarat because he was a Dalit. Another man was killed because he was seen riding a horse. So, yea, go ahead and tell me that what you’re going through is so difficult.

I glowered but there was nothing I could say.

“Brahminism is the poison which has spoiled Hinduism,” Ambedkar once stated, “You will succeed in saving Hinduism if you will kill Brahminism.”

I informed my parents that if I have kids, none of them will do the thread ceremony, no matter what family members say. Next, I prepare for my uncles seated around tables, reciting lines from pro-Modi sources.

They are yelling, and I’m yelling back.

***

Sudip Bhattacharya is a Rutgers University Ph.D. student in political science who focuses on race and social justice. He has a Master’s in journalism from Georgetown University. His work has been published at CNN, The Washington City Paper, The Lancaster Newspapers, The Daily Gazette (Schenectady), The Jersey Journal, Media Diversified (Writers of Colour), Reappropriate, AsAm News, The New Engagement, and Gaali Gang.