Just as curry doesn’t actually exist, neither does the diasporic South Asian. — Naben Ruthnum

Currybooks, Naben Ruthnum calls them. You know the ones: titles containing the words “monsoon” “spices” or the name of an exotic flower like jasmine or honeysuckle. Stories of South Asians, lost in the diaspora, negotiating the modernity of the West with retaining a sense of the homeland through familial bonds, old traditions, and many times, food.

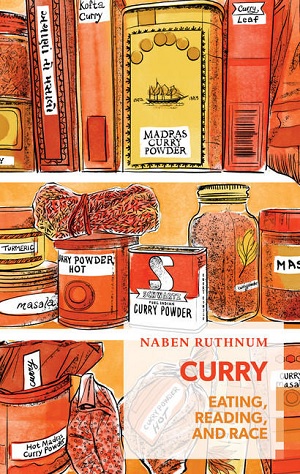

“Curry is not a cliché. Well, maybe it is,” Ruthnum writes in his book-length essay, Curry: Eating, Reading, and Race (Coach House Books, 2017). The concept of curry is an amalgam of a variety of regional traditions and hand-me-down family recipes, blended and bhurji-d to evoke an imagined India for Western palates, and it has, inevitably become a stand in for Indian cuisine overall.

“But curry can’t be trapped,” Ruthnum writes. “If you push through the cliché, you arrive at a surprising truth: the history of this ever-inauthentic mass of dishes is a close parallel to the formation of South Asian diasporic identity, which is as much of a blend of conflicting cultural messages forced into coherence as Indian cuisine itself.”

Much like its eponymous dish, his lithe tome is a tempered mish-mash of several genres: part critical study, part personal memoir, part cookbook, part travelogue. At times, it feels like a conscious attempt to defy definition, refuse any blurb-giver an easy answer to “what’s it about?” — an almost tit-for-tat for all the times a brown kid is asked, “Does your mom make curry at home?”

He bounds from essays to novels to films, everything from Scaachi Koul to Brick Lane to Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle. Threading it all, is this sense of qualifying the unquantifiable — how “Indian” is “curry,” and by extension, what exactly does it mean to be “South Asian” in a “diaspora”?

First, in “Eating” (like any good Indian mother, Ruthnum looks after the stomach first) the writer dissects the very idea of the Indian cookbook, and its insistence to contextualize cuisine with memoir — “…writing about curry and India and the real food of one’s ancestors becomes a meditation on personal and familial identity, and its relationship to the place where one grew up, or where one was wrested away from.”

Ruthnum subverts — playfully yet bitingly — the genre by adding his own facsimile of his mother’s recipe, going so far as to include her imprecise instructions including “about a heaped spoonful” and “the fish curry powder from Super store,” and remarking on his own additions: kale and sour cream.

With this interplay between his reading and his experiences, there is an undercurrent throughout the book of pleading with South Asians not to sacrifice the inconsistency of South Asian culture for the sake of being its ambassador to others:

“…the term Indian food may be inaccurate, but it’s not tyrannical: it represents a collective, shared brown identity that the products of the diaspora have uneven access to, a collection of modified dishes that touch on shared experience.”

This sets up the next two sections, “Reading” and “Race, which survey further works about and from the diaspora (the provided works cited appendix is a text treasure trove that is begging to be turned into several seminar courses). But the book avoids being overly academic. There is an even-toned freshness to Ruthnum’s language — critical without criticizing, pointed without being didactic — so that the discourse about these currybooks (and –films, -shows, so on) rises above.

Take for example this passage, while he’s skewering the 2002 film Bend It Like Beckham:

“Inventing a shared past to create a unified diasporic culture is, in part, the project of currybooks, of narratives such as Bend It Like Beckham, which are built on easily recognizable touchstone tropes. But the past can’t be altered to fit a desire for belonging and solidarity in the present: what people in the South Asian diaspora in the West share is that people looking at us assume that we all come from a similar past and place. But we don’t, and there’s no need to pretend that we do.”

For those who keep a steady diet of South Asian narratives, whether on their bookshelf or streaming account, it’s refreshing to hear. In a year when brown representation hit new highs, with the Rupi Kaurs and Kumail Nanjianis taking up where the Salman Rushdies and Jhumpa Lahiris paved as far as they could, that question always remains — Does this speak for me, and do I still have to support it?

Ruthnum couches it in his own experience, growing up in a small Canadian town in an Indo-Mauritian family, and then as a working writer, being nothing more than a consumer of the same products, sometimes giving in and sometimes staying away. Like all clichés, the currybook genre is derived out of certain personal truths, which have mistakenly become emblematic.

Curry is after all, no matter its form, a comfort food. In the end, Ruthnum has no real axe to grind with the currybook, only to call out the “embedded genre rules that can only be evaded by a determined writer.” It’s his call to the storytellers of today, you can have your curry and eat it too. But don’t mistake it for someone else’s.

* * *

Aditya Desai’s stories and essays have been featured by The Rumpus, The Millions,The Margins, District Lit, The Kartika Review, and other publications. He received his MFA from the University of Maryland and teaches writing in Baltimore. He is currently shopping his first novel.