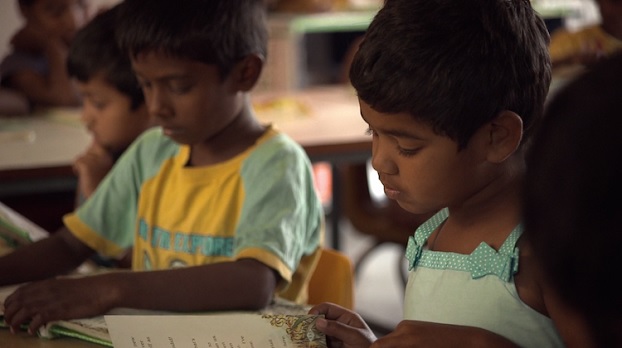

In early August, Netflix put out a four-part documentary by Oscar-winning director Vanessa Roth called Daughters of Destiny, about Shanti Bhavan (in Hindi: “haven of peace”), a residential school in Tamil Nadu for impoverished and lower caste youth.

The Shanti Bhavan Children’s Project was founded by Indian-American businessman Dr. Abraham George. George returned to India in 1995 “with the goal of making his contribution to reducing the injustices and inequalities he had observed from his travels throughout India.”

Shanti Bhavan prepares students for higher education, and subsequently, jobs that will uplift their families and communities. Students receive free education and housing until 12th grade. The school takes only one child per family (to spread its resources as wide as possible) and 95 percent of the students come from Dalit communities, the historically oppressed class of India’s caste system. S.B. students have gone on to be doctors, engineers, journalists, lawyers, and more.

The documentary follows five girls — Thenmozhi, Manjula, Shilpa, Karthika, Preetha — along their journey of life inside and outside of S.B.

Though the documentary shows all the good S.B. does for its students, Daughters of Destiny also portrays how the school is a microcosm of the different cultural clashes happening within India — the triumphs and challenges of S.B. students on the road to college or as they enter the workforce. While India just elected its first Dalit president, many of the roughly 300 million Dalits in India continue to face a myriad of social and economic hardships. Those who get to college often feel that caste stigma follows them to campus.

Each of the five girls profiled speak candidly about their lives in and out of S.B., navigating the different worlds they inhabit, their determination to uplift their communities, but also the pressure to forego personal aspirations in order to land a stable job.

S.B. students are reared within a more Western liberal education, but eventually have to integrate back into more traditional Indian society. This hybridity causes tension in their lives — growing up relatively privileged at S.B. while their families remain in impoverished settings back home. While S.B. is a place where education is essentialized, the poverty that many of its students’ families live in compel Dr. George and staff to approach education and the type of fields they encourage students to go into with a more pragmatic, teleological lens.

The documentary also tackles key issues of gender. Deepthy R. Chandran, a Research Scholar in the Department of English at University of Delhi has written that in India, the family, caste, religion, and the dominant value system are “surcharged” with patriarchy.

India has had the lowest female literacy rate in Asia. Within parts of Indian society, women are relegated to rigid gender roles. The girls recall stories of their female loved ones leaving school at early ages, and being sent off for marriage around 11th or 12th grade. One talks about her grandmother wanting to marry her to her uncle, another is expected to do cooking, cleaning, and other housework for her brother whenever she visits home while on break. While all the students at S.B. face certain hardships because of their caste, the girls face specific struggles that their male counterparts do not.

But Daughters of Destiny shows the importance of empowering underserved groups, especially women and girls. It shows the altruism of S.B. without romanticizing the societal challenges it is trying to address. It is an engaging and thoughtful film that humanizes the politics of education, caste, and gender in India.

* * *

This post originally appeared at https://medium.com/@journojoshua, where you can find more writing by Joshua Adams. Joshua Adams is a journalist and part-time instructor from Chicago. He attended both UVA and USC.