[TRIGGER WARNING] This article, and pages it links to, contain information about sexual assault and/or violence which may be triggering to survivors.

Angie* NMNH is the moniker of a National Museum of Natural History research student who was sexually harassed in 2011. She was not able to rely on the institution’s sexual harassment policies to protect her when she and her abuser crossed paths again in 2015. In fact, an internal investigation found that institutional policies had not been violated.

Her traumatic experience and constant fight to protect herself are thoroughly documented in this 2016 report by The Verge and inspired California Congresswoman Jackie Speier — author of HR 6161 — Federal Funding Accountability for Sexual Harassers Act — to personally contact the Smithsonian Institution, which operates the NMNH. Almost immediately afterwards, Angie’s harasser was banned from the Smithsonian.

Angie’s experience is by no means unique. In a Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE) with over 600 scientists in 2014, 71 percent of women and 41 percent of men reported experiencing sexual harassment. Despite the prevalence of sexual misconduct, “esteemed” administrators and “star” scientists are mildly admonished (if at all), and victims rarely see justice. It took over two years, a public investigation, and the intervention of a government official for Angie to once again have a safe work environment.

* * *

Angie discusses dealing with sexual harassment at the NMNH in blog posts she has written about her experience. But, to prevent victims of sexual harassment from enduring the lengthy trauma she had to, she approached me to share her experiences dealing with sexual harassment in an academic environment.

When Angie was first assaulted, she hoped that by filing the report as soon as possible, she could move on. Because her harasser was not a NMNH employee, she convinced herself that this was a forgettable incident. “When you belong to a traditionally disadvantaged group, sometimes the only way to get by is to push your bad experiences and your worries into the back of your mind. You have to ignore some very basic facts in order to function on a day-to-day basis.” However, a combination of missteps by NMNH employees and the hiring of the assailant meant that she would not be able to leave this experience behind.

As her case was passed through the hands of various NMNH personnel, Angie realized she was fighting a system where the blame was shifting from her harasser to herself — where she was not innocent (“there must have been a misunderstanding”) and the perpetrator was not guilty (“this was a one-time thing”). She found that the goal posts for punitive action continued to shift in favor of her harasser; during this process, the Smithsonian promoted him from unpaid visitor to full-time paid fellow with a multi-year appointment. “I was told that the Smithsonian could not protect me — could not take any action that might imply that he was guilty, even though his confession proved that he was.”

“The issues Angie describes are often amplified for underrepresented scientists.”

The issues Angie describes are often amplified for underrepresented scientists. She writes: “Inadequate responses to sexual misconduct are yet another manifestation of institutional sexism and cronyism. Because of institutional sexism and cronyism, we judge people based not on their merit or their credibility, but based on their appearances. In order to come to terms with the necessity of collaboration, you have to accept the fact that your colleague who called you ‘too dark’ is one of the better guys in your department. We are able to shove these memories to the back of our minds because we are able to isolate them. And then, when we are reminded of our friends who belong to underrepresented groups and were forced out of science, we make little excuses in our minds about why we don’t need to fear the same thing happening to us.”

However, the privilege of repression does not necessarily apply to sexual assault. Angie explains, “It’s much harder to isolate memories that involve unwanted physical contact. It’s like you can still feel the hands on your body, and you can still feel the wave of fear that rushed up through your stomach when you realized that you had to run away.”

“I don’t know if others feel the same way and I cannot claim to speak for anyone but myself, but to me sexual assault is insurmountably personal in a way that other terrible experiences are not. And that makes sexual misconduct much harder to push out of my mind. So it’s like the floodgates have opened: I no longer have access to my selective amnesia, and all the mistreatment that I have endured for belonging to an underrepresented group — and all of my friends who had to leave academia — stay at the forefront of my thoughts. Unwanted physical contact robbed me of my ability to suppress my memories of unwelcome comments and unfair experiences. So I go to therapy now.”

* * *

Earlier this year, the following tweet went around the academic Twittersphere:

Things female academic scientists do when we get together w/ wine: provide each other w/ list of men not to ever let students work with.

— Natalie Wright (@coereba) March 19, 2017

These female academics form the first line of defense for their students. Angie and I decided to develop another.

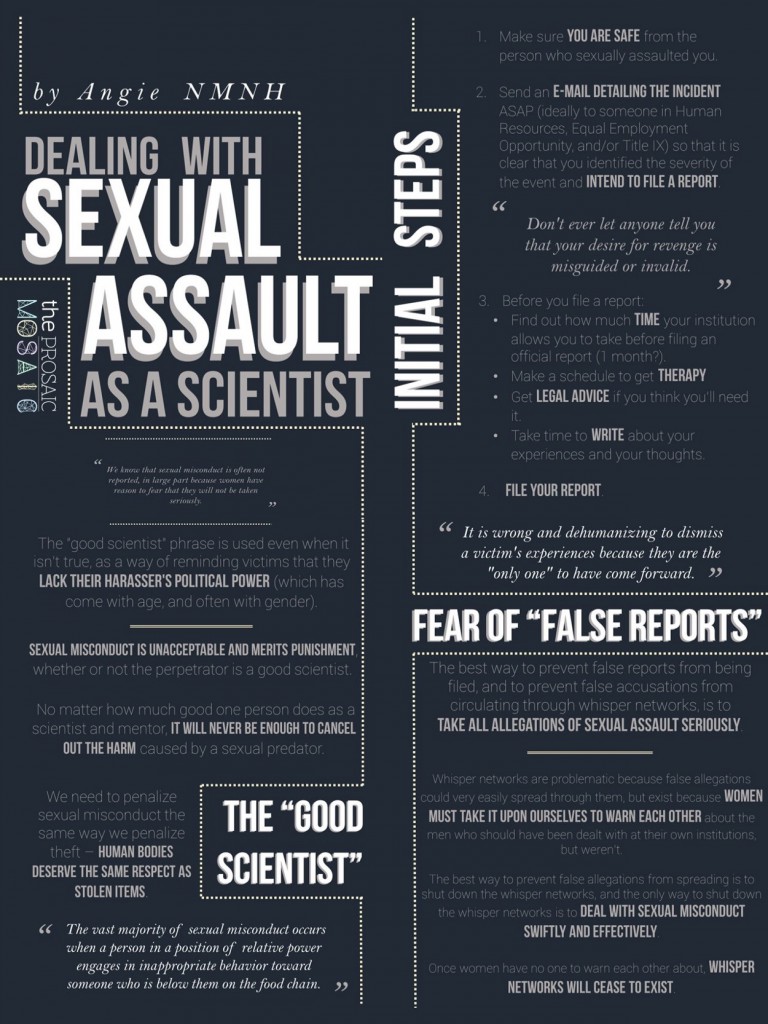

We created an infographic — “Dealing With Sexual Assault as a Scientist”. This is intended to provide a victim of sexual assault with the initial steps they should take to ensure they are caring for their own mental health while taking the necessary administrative steps towards reporting the incident. We also provide information on responding to two of the most common rebuttals victims of sexual assault face — that the (1) perpetrator is a “good scientist” and (2) the victim might be filing a false report.

We hope this information proves helpful to anyone dealing with or trying to improve their understanding of sexual harassment / assault in STEM. (Click on the image to view a larger version.)

* not victim’s real name

* * *

This essay was originally published at https://medium.com/@priyology, where you can also read more writing by Priya Shukla. Shukla is the ocean acidification technician for the BOAR Research Program at UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory. She received her BS in Environmental Science and Management (Ecology, Biodiversity, & Conservation) and minor in Oceanography from UC Davis, and MS in Ecology from San Diego State University.