Anjan Sundaram is an award-winning journalist who has reported from Africa and the Middle East for the New York Times and the Associated Press. His writing has also appeared in Foreign Policy,Fortune, the International Herald Tribune, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Telegraph, the Guardian, and the Huffington Post. He received a Reuters journalism award in 2006 for his environmental reporting on Pygmy tribes in Congo’s rainforest. He currently lives in Kigali, Rwanda, with his wife.

Anjan Sundaram is an award-winning journalist who has reported from Africa and the Middle East for the New York Times and the Associated Press. His writing has also appeared in Foreign Policy,Fortune, the International Herald Tribune, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Telegraph, the Guardian, and the Huffington Post. He received a Reuters journalism award in 2006 for his environmental reporting on Pygmy tribes in Congo’s rainforest. He currently lives in Kigali, Rwanda, with his wife.

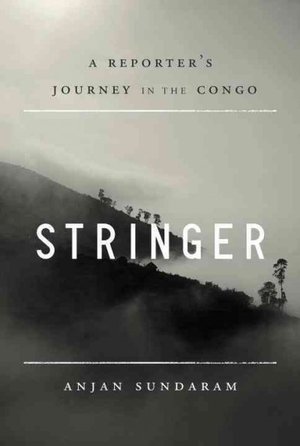

Stringer: A Reporter’s Year in the Congo is a haunting memoir of a dangerous and disorienting year of self-discovery in one of the world’s unhappiest countries. This chapter, excerpted by permission of Random House, describes Anjan’s unforgettable trip upriver, through savagely beautiful jungles, to an area where violent disputes frequently break out over reserves of valuable metal.

* * *

A sequence of wooden kiosks had been erected on the barge. Most were stuffed with supplies. A few were empty. The kiosks were near the center of the deck, where in a long pile running the barge’s length, goods were covered in thick nets. Around this pile were groups of people: passengers tending to their affairs. Some had come with food, others with rings of rope that tied together plastic canisters, called bidons. Boxes of imported whisky were guarded by vigilant agents wearing distribution company logos on their shirts. The goods traveled to be exchanged for rural produce: palm oil, roots, meat, banana wine and beer. A narrow corridor on the deck was not covered by cargo, and on this stretch of planks we walked. The wood was painted white, and led at the back to lavatories and quarters for the crew: huts that seemed little larger than pig cages. Sacks that crew members stepped over littered the doorways, and toothbrushes in metal cups lined window sills. Between the cabins were strung clotheslines from which identical overalls, torn in the same places—along the arms, over the chest, at the groin—flapped like pennants, dripping water in a pool that grew sideways with the gentle sway of the barge. Bobby and I were among the more privileged travelers: our quarters lay in a wooden kiosk. Its splintered planks gave us a roof but on the sides it was open to the world, and at night, the dark. Under this Bobby had set up our tent.

The barge’s pipes were dry. Carrying my toothbrush I scoured the boat, trying the taps at the stern, near the crew quarters and even in the captain’s office. But they only squeaked. Eventually I moved to a side, where the barge sloped slightly, and I scooped from the river with a mug. The water was translucent; twigs and winged insects floated. Everything in the water looked old. Brushing my teeth, I stood at the barge’s rear end, watching the river, as a remarkable scene unfolded over the water and along its edge.

We were quite far from the city already, and the houses onshore had thinned, giving way to green and brown bamboo and patches of red earth. Along the water villagers soaped their bodies and scrubbed clothes. The trees moved by slowly. And from ahead of the barge rows of pirogues set off with heavy loads and strong-armed rowers pushing against the riverbank with oars. The long, black pirogues were carried downriver and alongside our vessel; and the men frantically rowed, now coming at us from all sides, from the far horizon of the river and along its length, shooting out of the jungle like arrows. The barge was soon surrounded and the crew gathered at the bow, watching anxiously. All at once the rowers flung thick black ropes, like snakes, from their pirogues. A bell was rung fiercely near the captain’s quarters and the crew poured out of their rooms. Ropes flew through the air in high arcs and lashed at the barge, wriggling on the deck, slipping away, falling into the water; they were flung again with more fury. The crew thrust forward, they pulled the ropes with venous arms; they screamed at the rowers. The pirogues fought the flow of the river, approaching and falling away. Our motor’s pitch heightened. The canoes were laden with heaps; they bobbed and rolled in the river, threatening to capsize in the swirling currents. The men heaved their oars and restored balance, rowing faster and more desperately until the pirogues drew closer, rose on a wave and dipped, and moved within our wake. Here the river was calmer. The crew tied the ropes to posts and the pirogues flowed steadily, without effort. The rowers drew their oars, dripping, out of the water; they breathed heavily. And by evening we tugged a collection of crafts like balloons wanting to drift away on the river.

We were quite far from the city already, and the houses onshore had thinned, giving way to green and brown bamboo and patches of red earth. Along the water villagers soaped their bodies and scrubbed clothes. The trees moved by slowly. And from ahead of the barge rows of pirogues set off with heavy loads and strong-armed rowers pushing against the riverbank with oars. The long, black pirogues were carried downriver and alongside our vessel; and the men frantically rowed, now coming at us from all sides, from the far horizon of the river and along its length, shooting out of the jungle like arrows. The barge was soon surrounded and the crew gathered at the bow, watching anxiously. All at once the rowers flung thick black ropes, like snakes, from their pirogues. A bell was rung fiercely near the captain’s quarters and the crew poured out of their rooms. Ropes flew through the air in high arcs and lashed at the barge, wriggling on the deck, slipping away, falling into the water; they were flung again with more fury. The crew thrust forward, they pulled the ropes with venous arms; they screamed at the rowers. The pirogues fought the flow of the river, approaching and falling away. Our motor’s pitch heightened. The canoes were laden with heaps; they bobbed and rolled in the river, threatening to capsize in the swirling currents. The men heaved their oars and restored balance, rowing faster and more desperately until the pirogues drew closer, rose on a wave and dipped, and moved within our wake. Here the river was calmer. The crew tied the ropes to posts and the pirogues flowed steadily, without effort. The rowers drew their oars, dripping, out of the water; they breathed heavily. And by evening we tugged a collection of crafts like balloons wanting to drift away on the river.

At once the pirogues unloaded. And there was even less space. In the morning Bobby and I climbed out of the tent and found our faces against bags of dried fish. It had been a night of noise and movement. The paths on the deck had narrowed. We squeezed between the crates and reached the rear end of the barge, the designated bathroom area, where we pissed off the edge. It didn’t feel awkward, or public—the barge was almost an exclusively male environment, and this permitted a level of both immodesty and squalor.

The pirogues were commercial vessels from the villages: and I realized that the scene I had witnessed was the attaching of the city with the jungle. The two quickly integrated. Men walked to and from the pirogues, over the ropes, carrying bottles, nets and livestock. They became for us a source of fresh food, and they relieved the traders of their city stocks. Negotiations sometimes lasted until the morning.

Most pirogues concluded their commerce and left by afternoon. I saw them detach from the barge and drift downriver towards their settlements. In the evening the traders, having few customers left, relaxed by their stalls to reggae and rumba. A pair of drums was used intermittently. The night ambience on the barge was of charcoal-stove fires and radio sets. What beer was available was shared, and when I was feeling social I would buy a couple of bottles, and drink a half.

There was no repose on the barge. Traders lay about the deck, limbs spread over their wares—one had to navigate them. A few stood out, attracting crowds. One sold coiled springs, toys that slunk from hand to hand. A man in a fishnet vest, for a little money, imitated animal sounds—hoopoe, chimps, forest buffalo.

The traders, I noticed, were poor city men. It showed in the way they ate cassava-dough from their palms; their shirts were soiled from wiping their mouths and faces; their slippers were broken. They drank from filthy mugs. The pirogue-men, although poorer, appeared less neglected, less outcast. So, it seemed that, like on 16th century ships with their crews of slaves and prisoners, Kinshasa had sent on our barge its lowest elements as emissaries to the provinces.

The barge advanced northwards, making a breeze against the rolling humidity. And soon even villages were rare: I was startled at how quickly we had left all signs of human development. Passing us was a constant level of jungle, without variation in the kind of tree—buttressed, stout, covered in woody creepers—or in the deep shade of green, the cauliflower-like crowns. The sound of the barge was a steady drone. All this created a distinct tension.

And it was Bobby who, briskly humming the tune to Kuch kuch hota hai, addressed this unease.

Flies covered the crates in clusters, unnaturally still, and rising as a slow cloud; fellow passengers, seeking shelter from the sun behind the cargo, were taken by surprise, exposed as Bobby moved the crates; their hands claimed the bags he shifted. But Bobby made new stacks with the cargo and the flies returned, followed by the shade-seeking crouching men. Room was made around one crate. Two others became chairs. And to pass the time on the slow-moving barge Bobby suggested we play checkers. He had brought a board and counters.

We took our seats. Bobby was clearly in form: from the start his counters flew across the red and black squares. But it had been years since I had played. I took long pauses. Bobby picked impatiently at the splinters on the crate. “You’re not in the game of the century man. Don’t worry so much about losing.”

By the second or third day word had spread and people gathered around us to watch. Dames had been one of Mobutu’s favorite games, Bobby told me. The market invaded our cramped space: men smoked over us; monkeys hung from wooden crucifixes; blocks of hippo fat and meat lay on straw mats, heated by the sun, attracting insects. Chicken ran loose, flustered by sniffing pigs, flapping their wings above their heads and clambering, half flying, over men’s feet. Cages were pushed out of the way; the pigs panicked, shoving their noses at the ground and chasing the fowl for the length of their leashes. But Bobby and I played on, immersed, and this was how we spent the time until one morning when we heard a shot.

There was the jolt, and the fright, but the emotions seemed somehow unsurprising—one couldn’t help but feel that we had been waiting for something to happen; that there could not have been more eventless days. The strain had begun to feel unnatural, too full.

A ragged soldier was at fault. His uniform was typical, scavenged from enemies: the shirt came from Kabila’s guard, his hat from an invading Angolan army and his pants, a darker green, belonged to eastern rebels; the pants were folded up at the bottom, revealing a hairless shin. I had seen him prancing about the deck in rubber flip-flops, inseparable from his Kalashnikov—tied to his arm with rope so no one could steal it. For the entire previous day he had walked about the deck like this, swinging his arm, the weapon unusable and its bayonet oscillating dangerously. This was the gun that had been fired.

In the clearing where the crowd had separated we saw him at the barge edge. Beside was the captain—still in short-white pants, and looking through binoculars. The barge had drifted relatively close to the land, and the captain seemed to point at the monkeys clambering over the branches. But the soldier shot uselessly. The fire from his Kalashnikov raised spikes of dirt on the riverbank, and the branches showed no movement. The animals were gone. The captain cursed openly. The soldier puckered his lips and made an obscene sucking noise.

Calm returned to the deck, but in a heightened way. The barge had been unsettled and made alert by the shooting. The soldier stayed on the deck with his gun. And people withdrew: some slunk into the hull; a few crawled along the ropes to the pirogues. Bobby carefully moved our board to the kiosk, where it was quieter, and we continued where we had broken off: with my counters frenziedly fleeing. He joked about how fast I was running, but his voice had hardened, and he looked over his shoulder. The stress seemed to find expression in his movements. The forest was unbroken, a stretch of drifting green. Soon my pieces were cornered. I was three strokes from annihilation when I played a lively combination, breaking a portion of his defense and stalling his conquest. “You’re just delaying the end,” he said.

“I’m playing to win.”

Bobby got up from his seat, as if taken by an urge. He told me to wait and made for the back of the barge. The evening was coming to a close. The sun hung over the water, which glistened red and gold. Migratory birds skimmed the river surface, on their last legs before nightfall. Monkeys screeched across the water, their calls echoing. I could have waited half an hour; it felt too long.

Then, over the crates, I saw Bobby with the captain. They were sharing a smoke. I was about to call out when Bobby looked over and waved, as though nothing had happened. At first I was perplexed. Then I felt cheated. I tipped over one end of the board. The act was involuntary—I was surprised that I had done it; but already on this journey I had begun to feel outside myself. In this strange landscape, with its strange people, the monotony had begun to make me feel detached, distant, and it was as though by that act I had for a moment removed years of manners and teaching, obeying a destructive instinct. It somehow satisfied me to see the counters scattered over the deck.

The AP informed me that I was missing a number of stories in Kinshasa. The government had begun to make a number of election announcements. Bentley had returned to Kinshasa, and was reporting a flurry. The editors called to ask where I was—though they had known about my expedition. The line was crackly. They were annoyed. They asked how long I intended to travel. I had also missed earnings from those reports. I thought of the family in Kinshasa. And I felt a creeping doubt—if I had not erred by coming to the jungle. The pressure on me grew—the fear of coming out of this empty handed.

###