I used to live in Saudi Arabia, where Ramadan is a big deal. You’re expected to fast and if you can’t, the rule is you’ll respect everyone else by not stuffing your face in public. School hours shift. Store hours change too, and nothing is open until after iftar, the meal you have at sun-down to break your fast.

At night, the streets burst to life, and there are bright lights and music, and kids stay out until one in the morning. That’s another thing that changes: you go to sleep super late, wake up super late, and in this way for a month, everything is turned on its head.

“When I come to the United States to go to college, it’s as if Ramadan doesn’t exist.”

When I come to the United States to go to college, it’s as if Ramadan doesn’t exist. It’s up to me whether I want to be Muslim or not, in that there’s no one, not my parents, not the Saudi government, policing what I do or wear or eat or when. But I want to be Muslim, a good Muslim. I want to be a good person, and if the religion I was born into is handing me something that looks like a roadmap, I’m going to take that roadmap, and I’m at least going to look at it.

***

I once heard author Vijay Prashad say he didn’t become American until he left America, and in a similar way, I predict I will be more Muslim now that I’m not in Saudi Arabia. Six years spent in Riyadh took any curiosity I had about God, and drummed it right out of me. Now that I’m on my own, I’m curious again.

There are some basic tenets of Islam. I don’t know if following them will bring me closer to what I’m looking for. They say no alcohol, which is fine. No sex before marriage, no problem. Visit Mecca. Okay. Pray. Yes. Give to the poor. Yes again. Then there’s something about the occasional sacrifice of a goat or a sheep which I’m definitely not going to do. I figure I’m allowed to skip one. There should be a clause for the sensitive, the animal lovers, the vegetarians. Allah has to accommodate the vegetarians just like the rest of us do.

***

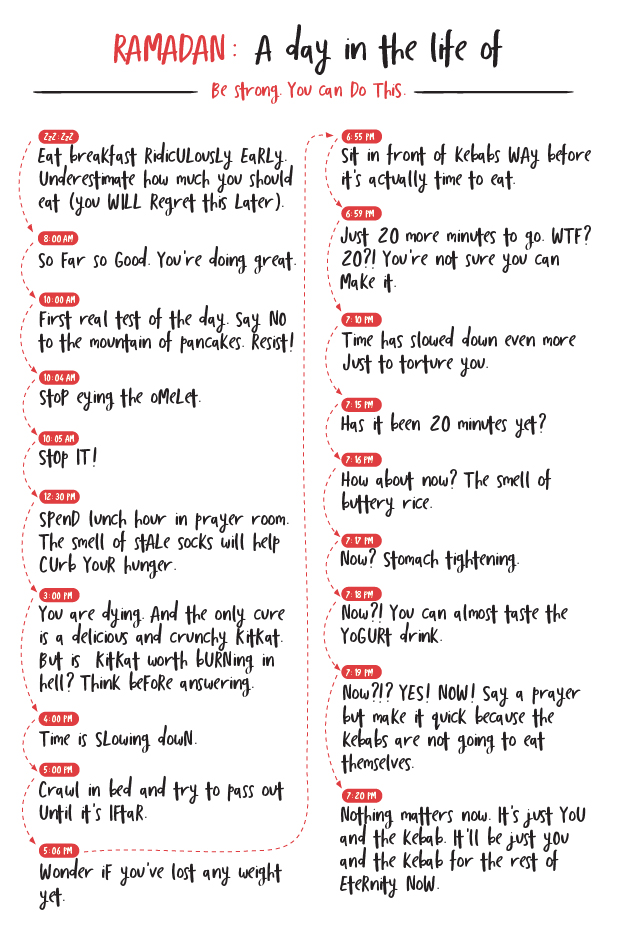

We didn’t really fast in my house, growing up and I don’t know what starving myself every day for thirty days will do to me. Maybe I’ll see more clearly, enter a state of unity consciousness, understand the point of everything in a flash. I have nothing but high hopes.

***

The first night, I eat before going to bed. There’s a crusty old microwave in the dorm-kitchen that I use to nuke a styrofoam cup of noodles. I eat that, eat an apple. I drink some Gatorade, and when my roommate wants me to go to the dining hall with her the next morning, I say yes. A test. What will I do, surrounded by unlimited pancakes? By giant cereal dispensers of off-brand Froot Loops? Mmm, off-brand Froot Loops. No! Resist. I will not cave. It’s only ten in the morning.

I follow my roommate as she walks around with her tray. We stop at the omelette station.

“I’m going to do Ramadan too,” she says.

I stare at the omelette she’s just ordered. A man in a tall chef’s hat is making a big production of it, stirring in some mushrooms with a spatula.

“I’m not going have sex with Ryan this month. That’s my Ramadan.”

“I’m not going have sex with Ryan this month. That’s my Ramadan.” She quickly crosses her heart which is weird because she’s Hindu. She sticks her hand out, little finger raised. “Hold me accountable, Hilal.”

We pinky-swear like the ancients must have done. “No Ryan,” I say. I say it enthusiastically, because I secretly hate Ryan, how he’s always smoking weed, cheating on Shalini. “Fuck Ryan,” I say. “You know what I mean.”

***

Instead of lunch that day, I go to the basement prayer room in the student union. It’s my first time. The room is windowless, but a slow-turning ceiling fan circulates the stale aroma of socks. The sock smell is familiar. I remember it from when my parents took me to Istanbul’s Blue Mosque one summer. I was a kid. We were tourists. I complained loudly about the sock smell, and my mom hushed me.

“Look at this stained glass for God’s sake!”

But I just couldn’t get into the stained glass because I couldn’t get over the smell. I think this was the only time my parents took me to a mosque. It’s the only time I remember.

***

My parents grew up in the new Turkish republic where being religious was seen as a sign of being a moron. In certain circles, this is still the case. There was a piece in a Turkish paper recently about the rise in “deizm,” or “yaradancılık.” Agnosticism. Experts think this turning away from religion is a direct response to the Islamist, right-wing regime currently in place, which sounds correct to me. In my own life, I have turned away from organized religion, too. The older I get, the more I turn.

“In my own life, I have turned away from organized religion, too. The older I get, the more I turn.”

But that afternoon, in the sock basement, I haven’t turned yet. There’s an imam leading the service. It’s a Friday, so he delivers a sermon to start things off. He talks about the importance of chastity, of lowering your gaze around the opposite sex. I know he’s talking about me specifically as I’ve been sitting on my prayer mat, staring at all the Persian hotties in the room. I am the person for whom this Islamic law was written.

***

By the time we’re dismissed, and my bio lab begins, it’s three in the afternoon, and I’m on my last legs, so to speak. I drag myself to the bench, collapse against it, rest my cheek on the cold metal table. I tell my lab-partner the success of our fruit fly experiment rests in her hands.

“I’m dying, Ying-Ying,” I explain.

Ying-Ying is sympathetic. “I have a Kit-Kat in my bag. Do you want a Kit-Kat?”

“I’ll burn in hell.”

“For a Kit-Kat?”

“Yes, for a Kit-Kat,” I say, irritated. “I don’t make the rules, Ying-Ying.”

When I shut my eyes, I see floating black spots. When I stand to go to the bathroom, I have to sit back down again because I’m worried I’ll faint. I am angry for no reason.

Why is this so hard? Why was it never this hard in Saudi Arabia? Probably because during the rare fast, I slept until three in the afternoon. I didn’t walk around a campus, taking pop quizzes and examining fruit flies. Probably because in Saudi, I ate like a bear for suhur. Instant noodles are no kind of suhur. Lesson learned.

“Instant noodles are no kind of suhur. Lesson learned.”

***

There are about two billion Muslims in the world, and some fraction of them fast, and they do it under difficult circumstances. They are factory workers in Erzurum. They are cab drivers in New York. They are doctors, and school teachers, and waiters, and plumbers.

I can’t say I’ve ever felt a deep or abiding sense of kinship with Muslims as a general population, but that afternoon, I begin to feel the stirrings of something. Admiration, definitely. How do they abstain from food, drink, drugs, sex, alcohol, gossip? How do they do it for so long, day after day, year after year? How is it that they are strong, and I’m so weak?

***

Back in my room, I crawl into bed and pass out. Next thing, Shalini’s holding her phone to my face.

“Guess who?” she says. “I told him to go fuck himself.”

I give her a thumbs up.

“Happy Ramadan,” she says.

“Happy Ramadan,” I croak.

***

For iftar, Shalini and I drive to Moby Dick’s in Georgetown: a hole in the wall with the best kebabs you will ever eat in your life. On the ride down, I wonder if the way a person fasts says something about how she experiences the world. When things get tough, does she get tough too? Does she buckle? Grow angry and resentful? Surrender to what is? If she can’t control her various carnal appetites, do they ultimately control her?

“I wonder if the way a person fasts says something about how she experiences the world.”

When it isn’t Ramadan, I eat when I’m hungry, when I’m bored, when I’m feeling awkward at a party. I go to coffeeshops on a whim, fuel myself with drinks that come out of a blender. I eat to survive, to distract and numb, to savor. I don’t think twice about any of it. But with food gone, with my vision blurred and my heart rate slowed down all the way, things are different. It’s true that I feel a shift. I feel clear and still and aware. Something in me has gone quiet.

***

I remember everything about the last twenty minutes before sundown that day. I can close my eyes and conjure up the shine of Shalini’s hair, the beat of the Biggie track on the radio, the black asphalt a blur under our fat tires. I can smell the buttered rice, picture Shalini sliding my kebab off its skewer, pouring my yogurt drink into a clear plastic cup. I can feel my stomach tighten.

***

That year, I won’t fast all of Ramadan, but I will fast for most of it. I believe doing this opens me up to others in a new way. I will begin volunteering at a food bank. I will do this because I have a sense now, the smallest of senses, of what it means to want but not have. I will do it because I realize most who are hungry, aren’t hungry by choice.

***

Outside Moby Dick, the sun is setting. I spear some meat with a bendy white fork and stare at it for a moment. I’m supposed to say a prayer, but I don’t know which one. I take a bite and chew slowly. In the name of God. Most gracious? Most merciful? My ears are ringing. Gracious, merciful, and then? I take another bite. Where have the rest of the words gone? Char and salt fill my mouth, and I can see that I have forgotten the words. I can see I have forgotten them all.

***

Hilal Isler helps edit Muslim Women Speak, an online publication now open to submissions.