This month marked the 67th anniversary of pop music megastar Freddie Mercury’s birth. The musician, singer, and songwriter best known as lead vocalist and lyricist of rock band Queen died over two decades ago. But his spirit lives on and continues to inspire others. Queen band-member Brian May recently announced that there may be a posthumous Queen album released in the near future, featuring not only Freddie Mercury but an equally eccentric and grandiose Michael Jackson. A biopic of the star’s life is in the works too, with rumors swirling that actor Daniel Radcliffe (Harry Potter) is being considered to play the British rocker. He would replace Borat actor Sacha Baron Cohen.

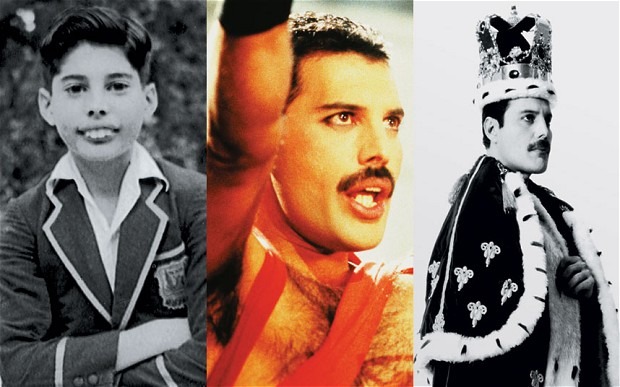

Freddie Mercury is perhaps lodged in your mind as that iconic British rock star, the philandering partier, the serial maker of over-testosteroned-anthems. Re-imagine him as someone less familiar: Farrokh Bulsara, a demure, bucktoothed Indian boy in a Bombay boarding school, listening to Lata Mangeshkar, playing cricket.

Curiously enough, the one thing Freddie Mercury was never asked, nor spoke openly about, was his Indianness.

Queen band member Roger Taylor said in the documentary A Kind of Magic (YouTube) that “[Freddie] did play it down a bit (being Indian). I think it was because he felt people wouldn’t equate being Indian with rock and roll.” Why was rock n’ roll loathe to claim an Indian and why have Indians been loathe to claim this rock icon? Was it because he was queer — in every sense of the word? Was it because Mercury himself downplayed his ethnicity?

Freddie did not spend his childhood the way one would imagine a British rock star from, say, Liverpool, would have spent his youth. He was not squatting in industrial buildings at 15, he did not eat bangers and mash for brunch (until later, anyway), and he did not have a fully British accent when he was ten. Nor, for that matter, was his name “Freddie.”

Farrokh Bulsara was born in Zanzibar, Tanzania, to Indian Parsi parents. Parsis are observers of the ancient religion of Zoroastianism. They are a miniscule Persian ethnic group who migrated to the subcontinent thousands of years ago during the spread of Islam in Persia. Farrokh, like most Parsis, spoke Gujarati, and grew up on the tiny streets of the East African coastal nation. At ten he was sent to St. Peter’s, a boarding school in Bombay. He grew up watching Indian films during its booming years, and was said to have enjoyed the music we now might call “Bollywood oldies.”

Freddie experienced and embraced oddity early on. When he was sent off to Bombay at ten years old, where he became the outsider — a demure newcomer from the Zanzibarian coast who quickly became flamboyant with his artistic talents. Peter Patrao, his old math teacher once said, “he was a fairly nondescript boy with buckteeth. The children would call him Buckie, which he hated, and that might be how he came up with the name Freddie.”

At the age of 17, when he moved to England, his Indian English probably wasn’t the most vogue accent in town — in fact, it was frequently noted he was ridiculed for it. There wasn’t a socio-cultural category available to Freddie during his time — his foray into music happened only a short while after India’s independence from the British Raj, and racist Victorian sentiments on ethnicity and sexuality still persisted. That, and never before was there an Indian-East African-Parsi-queer-rock-opera star.

[pullquote]Never before was there an Indian-East African-Parsi-queer-rock-opera star.[/pullquote] Maybe the question is not only why he wanted “hide” his Indianness, but also why he wanted to pass off as “white” — or if he cared about any of these identifying categories at all. Freddie never even disclosed biographical details of his past in his few recorded interviews. Did he want to assimilate in the British world, and did he ever? Did he feel always alien no matter which culture he found himself in? Was he stuck between worlds — or liberated from all?

There is also the angle of the Indian world — and the Parsi community — who, similar to Freddie’s still Victorian social climate in Britain — were steeped in puritanical dogma and traditional beliefs. It was no surprise that even Indians did not approve of his lifestyle, of brazen flamboyance from a man of their community. His audacious tenacity, prodigious melodies, and haunting ballads may hold elements of his frustration with the inability to properly “fit” — and so he did the opposite: he erupted into a flame of beautiful and dramatic ambiguity, a magnificent spectacle.

There were no Indian rock stars in England then, sure. But there were also no Indian rock stars in India at that time. Or Tanzania. Let alone queer, Indian, Parsi, third-culture-kid rock stars in India, England, or Tanzania.

Freddie could not refer to any identity or trajectory other than his own. It is clear from interviews with his family and friends that he was not self-hating, he was not the type to deny or confirm his sexual orientation, or ethnic background. His silence or dismissal about his cultural background — and one so formative and dramatically different than British life at that — can be interpreted as a political and social symptom of his time.[pullquote align=”right”]Freddie could not refer to any identity or trajectory other than his own.[/pullquote]

Freddie lived in the same Britain that has given the world its Victorian feelings about desire, sex and gender. Perhaps he rejected British Victorian taste at the same time he rejected his Indian Africanness. Even American liberal Lester Bangs was made uncomfortable by Mercury’s bare chest. What we call “queer” now with feelings of empowerment, back then was still scary and threatening even on the music scene. Did he consider himself British? Or like Bowie who came after, an alien altogether?

Was identity, for Freddie, not British or Indian, African or English, but nothing at all related to country or creed? He let these identities have contradictions and multiple definitions, especially in songs like “Bohemian Rhapsody,” or “Mustapha,” where nothing even makes linguistic sense. Perhaps his embrace of neologism hinted at his disdain for categories. Perhaps his music manifested his apathy towards coherence, and labels.

Take, for example, September 1978 — his prime. He was handsome, with an angular though slightly bovine jaw, and vaguely ethnic features. Even as someone unfortunate enough to have never witnessed his performative tenacity in real life, the visual archives of Freddie Mercury make certain things apparent: he was magical, soft-spoken, and — to complicate and contribute to his slew of paradoxes –clear that he was the toughest, coolest queen the world had ever seen, whose work, as effeminate and genderbending as it was, is still considered pretty manly today.

V.S. Naipaul once said: “write every book as though it is your last.” Freddie, with vatic intuition, took a page out of that book, and sang every song with the same sentiment. One seldom finds artists who exalt both abandon and irony as debonairly as he did.

Despite the fact that he seemed to dismiss categories, reject a slew of social norms, he was ironically, a creature of caricature, of extremity, and high-Victorian causticity: “There’s no half measures with me,” Freddie said in one of his last interviews, unintentionally referencing an apt musical notation. From the dramatic flippancy of his costumes, to his 4-octave baritone perusing vocal extremes with relative abandon, to the fact that he — without doubt, and to the agreement of nearly everyone who lived in his era — defined what it meant to “party like a rock star,” Freddie was not one for subtlety when it came to his artistic prowess.

And it is also possible that Freddie was not “stuck” in multiple worlds — though he was rejected from most — but liberated. And maybe he had the right idea about culture — that he was not Indian, Zoroastrian, British, or Zanzibarian — but quite simply, he was all that became of his passion: rock ‘n’ roll.

Correction: This post has been updated to reflect the correct number of octaves in Freddie Mercury’s vocal range.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Brown Town Magazine, where Janaki Challa is the founding editor. Her work has appeared in Catamaran, India Abroad, EGO, In the Snake, and The Revealer. She was a graduate student at New York University, and is now an intern at NPR in Washington, D.C.

O-ho, “bovine jaw.” Freddie mamu deserves better than that. 🙂

Freddie would have been 67 years old. Freddie said he was Persian in an interview and he was correct. It’s somewhere on youtube.

This is a fine article, but at the end it says his voice was ‘8 octaves’! No-one’s voice is 8 octaves!! I’m sitting front of the piano right now and there are a maximum 6-7 octaves on a full size keyboard depending on how you read it. Freddie was a pretty solid tenor with some nice low notes, a truly great singer, but his voice was not a freakish improbability.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan had a 6 octave voice

4 octaves