Launched in 2013 by Nicole Cliffe and Mallory Ortberg, The Toast came to a close on July 1 — though its archives will remain online for admirers of its quirky humor and hilarious and illuminating approach to a diverse range of topics. The publication will be missed by many, including the potential next President of the United States. With Friday’s “A note on The Toast” Hillary Clinton revealed herself to be a fan of the feminist space on the web where women spoke their minds freely. We’ll miss The Toast too, and we’re taking a look back at some slices of brown experience published on the website. These are pieces of The Toast that shared all kinds of thought-provoking desi stories and reflections, and you can read the full essays by clicking on the headlines. Grab some ghee, maybe some chutney or cinnamon too, and have a chew.

“A’ghailleann”: On Language-Learning and the Decolonisation of the Mind

Iona Sharma is a writer, lawyer, and linguaphile, and the product of more than one country. On The Toast she wrote about learning Hindi and Gaelic:

And, as ever, it matters because the personal is political. It matters because Hindi, like Gaelic, is a colonised space. It is a language complete in itself, with its own history, literature, poetry and tradition. But more than sixty-five years after Indian independence, it has been surrounded and absorbed by English, so among the Indian middle classes it is no longer a prestige language. It is the vernacular, the language one speaks at home; one does not use it to write to the tax office, nor take one’s degree.

On Painted Hands and Soccer Pitches

Shireen Ahmed is a sports activist and a freelance writer who focuses on Muslim women and the intersections of racism and misogyny in sports. Read her entire essay for her memory of being 12 and being noticed and embarrassed by other players for wearing henna while playing soccer.

Recently, while doing research for a piece on women’s football in Europe, I came across a gorgeous photograph of France’s superstar midfielder, Louisa Necib. Necib, one of my favourite players, sits on the bench, getting ready for a training session with the women’s national team. Her hair is in a practical style, and she is pulling up her socks and adjusting her shin guards. Completely normal. Except for one tiny detail that caught my eye: her hands were decorated with henna.

https://twitter.com/DavidSRudin/status/739204082829692929

At Home, Twice Removed: Living In Triple Exile

Gauraa Shekhar is a freelance writer working on her first book and a music supervisor who divides her time between New York and Mumbai. Read about her global upbringing and its influences on creating her own identity.

Could I not be part of a culture I wasn’t born to? I wondered. Was I supposed to unlearn who I was and what I knew to fit the Indian societal perception of who I should be? How could I, an Indian-Indonesian hybrid and American pop-culture obsessive, fit into “my” culture? What even constituted “my” culture? And why should anybody besides me set my cultural parameters?

Firangi: Confessions of an Albino Muslim in India

Mehak Siddiqui is an author living in India. She is currently writing her first novel, which draws heavily from her experiences living and growing up with albinism.

Other times, having albinism puts me in a rare if not non-existent class: I am a native South Asian Muslim with “white privilege.” One might not think that this applies in a predominantly non-Caucasian country like India, but my daily life is sprinkled with incidents where, shoulder-to-shoulder with my family, friends, and peers, I am afforded a higher status simply because of my appearance. Like a spy in my own homeland, I slip past the racial barriers that tightly bind my loved ones to the drawbacks of their own culture.

Ten Scenes From My Bollywood Marriage

Rashi Rohatgi teaches in London and reviews books at Africa in Words. On The Toast she reflects on her interracial marriage and shares scenes from her childhood, courtship and post-wedding life with her husband.

3. When I get to school myself, I count a lot of white people. They’ll become my closest friends and unshakeable Facebook hate-stalkees, but logic also tells me something else. Odds are my Bollywood wedding will have an extracanonical – white – groom. I should probably see how I can fit one into the picture. Luckily my entire education seems to be geared towards teaching me about white men and their world.

Ten Scenes From My Bollywood Marriage – Rashi Rohatgi @TheToast https://t.co/MOvFlgn0Fb pic.twitter.com/UBZN39YaWA

— The Aerogram (@theaerogram) April 16, 2016

Some Unorganized Mixed Race Thoughts

Jaya Saxena, staff writer at The Toast, wrote about being mixed race and how she feels about writing about race.

I don’t want to see people like me in media. I want to see me. I realized this while watching Quantico, where Priyanka Chopra’s character has a white father and an Indian mother. Her family makeup is the closest I’ve ever seen to mine but no, she’s from California and lived in India and is darker and has better hair. That’s not me. Neither is Aziz, living in New York and eating sandwiches from Parm but dealing with racial stereotypes, or Gwen Stefani with her zippered pants and bindis but blonde hair, or anyone with whom I’ve partially identified over the years.

The Customer is Not Always Right: Microaggressions in the Service Industry

Saher Naumaan, currently an MA Candidate in the War Studies Department at King’s College London, worked as a server, barista, and bartender in Washington, DC.

Working in the service industry, I was so often reduced to a single idea that some stranger had about me. I was identified, pinpointed, as a brown South Asian woman, which in itself holds a number of associations for people… I could be all of those things, but not a struggling writer, a soccer player, a die-hard Manchester United fan, a very-in-debt Master’s student, an aspiring intelligence analyst, a feminist, a disillusioned diasporic. To some people, I couldn’t even be an American, because I am Muslim and brown.

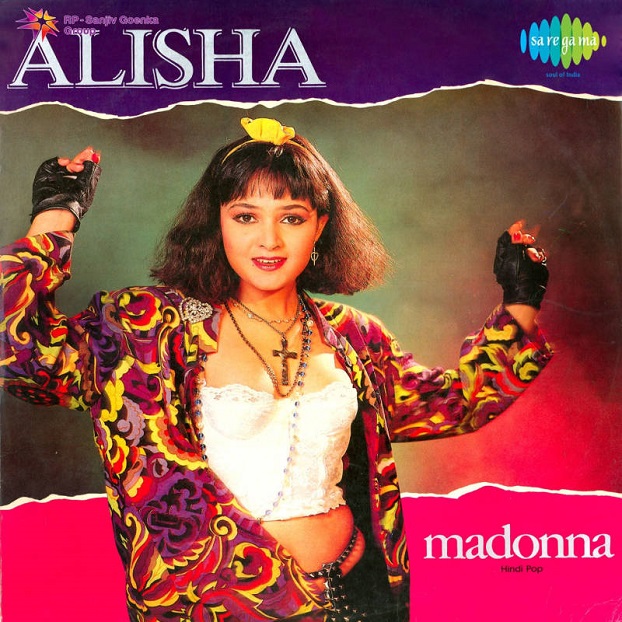

A Bollywood Madonna Covers Album and the Sound of Our Reparations

The Aerogram’s executive editor Rohin Guha wrote for The Toast about pop star Alisha Chinai. Read the entire essay for ruminations on pop culture, assimilation, appropriation, and reparations.

One day in the early 1990s, I rifled through my mom’s collection of cassette tapes and pulled one out that read Madonna. The cassette tape cover featured a pop star named Alisha Chinai, wearing a floral-print crop-top jacket over a black brassiere, cross necklaces reminiscent of “Like A Virgin”-era Madonna, and fingerless leather gloves. Everything about Chinai’s look was a flawless adaptation of the Material Girl’s style. At age seven, I already knew who Madonna was; I knew what a force she was–but this. This seemed like a secret treasure. “She’s like the Indian Madonna,” my mother told me.

The Convert Series: Aadita Chaudhury

As part of The Toast’s Convert Series talking with people who have changed religions, editor Mallory Ortberg interviewed Aadita Chaudhury.

My earliest memories of spirituality or religion is characterized by aggressive indifference to divinity and marked curiosity in the history and mythology behind religions. I treated them as fairy tales or high fantasy literature that simply took on special meaning for a group of people, so it was largely interesting to me ethnographically. I would not get any real religious education until I moved to Canada at the age of 12, and subsequently attended a Catholic high school.

The Reactions I’m Assuming People Want When They Comment On My Name

The Toast’s staff writer Jaya Saxena speculates on what people want when they bring up that sometimes annoying, sometimes sincere question or comment which many of us get on our names.

“Funny, it doesn’t sound Indian.”: It is funny. It’s hilarious. They made this name specifically to trick you, all of India, that is. Everyone got together and was like “we should have at least one name that doesn’t sound like it’s from here at all, and then maybe one day we can fuck with Mark.” They’ll be so happy to know they succeeded.

Why I Want an Arranged Marriage

Rohin Guha reflects on marriage and family, queer and Indian identity and why he’d want his parents involved in choosing his spouse. Bonus: a list of what kind of delicious foods might be served at his future wedding.

While approval from my parents on my ideal match is important, it isn’t critical. What’s critical is my parents’ ability to call a spade a spade. What’s critical is that after years of studying their marriage–a beautiful patchwork of inside jokes, compromise, and collaboration–they understand I’ve learned the right lessons. They’ve been part of that support structure that helped me with my math homework, stuck with me when I failed my driving test the first couple times, and–I can’t overstate this–didn’t cast me aside when I came out to them as queer. So it’s critical that they only have a say in who I elect to spend the rest of my days with.

The Good Indian Friend: A Manual

Neha Margosa lives in Bangalore, India. She’s interested in writing about music, food, and memory, and in this essay she shared her thoughts on what kinds of expectations might be had for a “good Indian friend.”

The good Indian friend is absolutely always able to hold long conversations on Bollywood.

“Can you teach me any moves?” The good Indian friend might often be called upon to become an impromptu Bollywood dance instructor. She will always be up-to-date with the latest moves, and will always be ready to demonstrate. The good Indian friend knows all the lyrics of every Hindi song ever written.

On Mississippi Masala and Being Seen

Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite is a writer and editor living in Toronto. Read her essay which looks at what made Mississippi Masala a unique and meaningful film.

It’s rare to find pop culture products that confront issues of racism within communities of color, especially when immigration is thrown into the mix. Mira Nair’s 1992 film Mississippi Masala acknowledges the diverse and complicated experiences of people who move to the U.S. and the inter-cultural racism that they deal with and perpetuate upon arrival. In the movie, the Loha family—Jay (Roshan Seth), Kinnu (Sharmila Tagore) and their adult daughter Mina (Sarita Choudhury)—are third-generation Ugandans of Indian descent who are forced to leave Uganda following the 1972 expulsion of Asians from the country under President Idi Amin.

How I Learned to Love My Skin Colour

Rumnique Nannar is a freelance writer and “a part-time masala film preacher on the street corner” who shared how she felt about and how others made her feel about her skin color.

I used to hate my skin colour. If you described it as a foundation shade, I’d be Mocha or Tan+++. I’d always felt like the dark one in most school or family photos, a feeling that was accentuated when I moved from London to Vancouver, where I was often the only brown person in my circle of friends. Coming from a Punjabi family, I felt like an anomaly standing next to my parents and sister, who all share a certain fairness of skin. But true inner hatred wasn’t unleashed until my prom night in Canada.

If Kal Penn Were Your Boyfriend

Cross-platform and -country friends, Victoria Baritz and Sulagna Misra met through Tumblr when writing about Chris Evans. They joined forces to write about Kal Pen too for The Toast’s wonderful “If X Were Your Y” series.

If Kal Penn were your boyfriend, you’d having a running joke with John Cho about monitoring Kal Penn. “He’s watching a lot of cartoons,” you say. “Mm, he does that sometimes when he’s blocking out childhood memories. How’re his bowel movements?”

Symmetry in Our Misshapenness: On Learning How to Belong

Masooma Hussain has her roots in Karachi and her branches in Toronto. She spends her time writing and performing comedy, analyzing pop culture, and crafting her aesthetic.

I yearned for connection with my peers and lost a part of myself in the process, and only recently have I realized how many others have done the same. Reading the work of writers like Hamid, Siddiqi, and Chew-Bose, I find comfort in recognizing a shared experience of being displaced. Our first-generation experience is not that of our parents, and caught in the space between here and there is a new home. There is a sense of belonging in reading Chew-Bose affirm that she will no longer erase herself to make white peers more comfortable.

Thorns in My Throat: Writing Through the Scars

Shveta Thakrar is a writer of South Asian-flavored fantasy, a social justice activist, and a part-time nagini.

When I write, I have no desire to plumb my characters’ angst about being brown; I want their skin color to be taken for granted while they go on fantastical adventures. If those adventures can include Hindu and Buddhist mythology and folklore, so much the better. We need those. But I’m not sure why I need to keep explaining that such a book would not be niche—that in fact, I am not niche?

Adventures in Immigration: Winter Blues and Culture Shock

Aadita Chaudhury is a graduate student and writer based in Toronto who has been known to moonlight as an engineer and a poet.

I don’t remember exactly when I realized that something was indeed wrong, but it must have been sometime just after my thirteenth birthday. A few months prior, my father and I had arrived in Toronto from our small university town in India. I had little idea as to what awaited me, although I had visited Canada before and had some limited experience with harsh Himalayan winters. My parents had lived abroad and traveled widely both before and after I was born, so I expected my culture shock would be limited. I spoke English perfectly, was reasonably outgoing and academically oriented, and we all assumed that adjusting to our new urban Canadian setting would be no problem for me.

Why Home is a Bad Bollywood Movie

Sayantani Dasgupta teaches at the University of Idaho and serves as the nonfiction editor of Crab Creek Review.

I was too young to realize it then but 1991 was a year of change, not just for me but for the country as a whole. Only recently, India had opened its shores to economic liberalization and we were on our way to golden-arched restaurants selling happy meals and cola giants fighting to quench our thirst. Inside our homes, though, we were still being raised with “wholesome Indian values,” one of which was no dating, at least not until college.

Girls from Good Families

Soniah Kamal’s debut novel is An Isolated Incident. She is also an essayist, literary critic and book reviewer.

In the Pakistan I returned to, control was focused on preventing the unmarried from gaining sexual knowledge or having pre-marital sex. Because sex outside wedlock is illegal in Islam, Pakistanis—Muslims everywhere—form entire morality enforcement industries to make sure the genders are kept separate in order to avoid temptation. Thus the “concerned citizens” telling me to wear long-sleeved apparel only and cover my chest with a dupatta. Everything is everyone’s business, and those of us girls who were curious about sex were suspect because good girls from good Muslim or Pakistani families do not even think about sex. And they certainly do not write about sex.

Porkistan

Syed Ali Haider was born in Pakistan, grew up in Florida, went to college in Minnesota, and finished his degree in Texas where he writes, teaches, and cheers for the Detroit Lions.

For the past seven years, I’ve been unable to leave South Texas, and I blame the food. Tex-Mex and Jalisco-style taquerias. Dishes identical in taste and smell to the Pakistani food I grew up eating but have been without for some time. Meat and potatoes served with a side of rice. Carne Guisada Con Papas is Aloo Gosht. Aloo Qeema is Picadillo Mexicano. Sometimes we fold it into roti or naan like a taco. My father unwittingly scrambled our eggs with onions, tomatoes, and Serrano peppers à la Huevos Mexicanos.

“Brown and Queer in America”: On Being a Bridge

Mona is an aspiring academic living far away from home. This essay for The Toast shares what it’s like for the writer to explain and interpret for everyone as a brown and queer person in America.

But now you know that when you are both brown and queer in America, you have to interpret for everyone — your liberal straight friends from your old life, your queer friends from your new one, your pragmatic family that believes you can think your way out of any uncomfortable taste or tendency if you try hard enough. You’ll have to be the lens through which “progressive” America, where you learned to think, can view the “traditional,” “conservative” culture you come from — you know the one, where Hijra is a gender you can put on your I.D. card, and you’re named after a female incarnation of a male god — and vice-versa. It doesn’t feel like a superpower anymore; it feels like a burden you do not want to bear.

An Interview With Tanuja Desai Hidier

In this interview, writer and editor Safy-Hallan Farah asked the Born Confused and Bombay Blues author Tanuja Desai Hidier about her books, her music, and advice for writers.

My advice is the same for any aspiring writer — regardless of age, gender, skin color: Never underestimate the power of your own story, if you want to write from this vantage point. The things that may seem the most mundane to you may be your hook, as these are the most organic to your experience, your particular perspective on the world. But — and this is very important — nor should you feel obliged to write from these specific vantage points: Part of what a writer does is get under the skin of different characters, different worlds, to the place where our hearts beat in time.

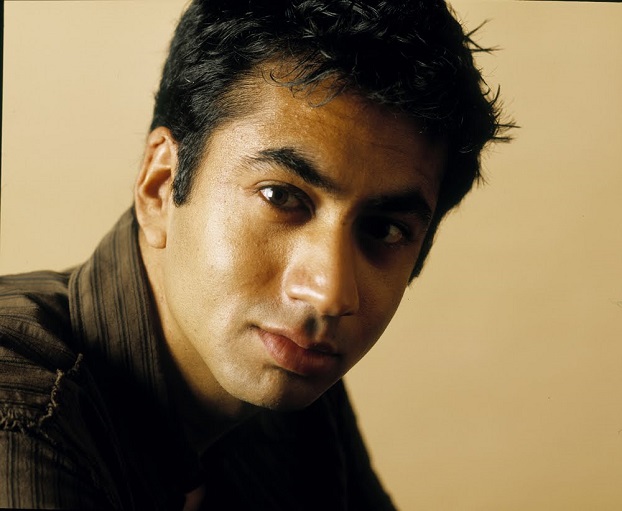

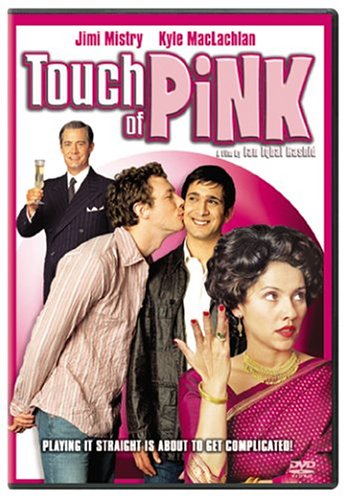

Watching Bad Gay Movies With The Aerogram

Take a chat journey with The Toast’s Mallory Ortberg and The Aerogram’s Rohin Guha as they watch Touch of Pink starring Jimi Mistry as a gay Canadian man living in London to escape the domineering eye of his conservative Muslim mother, Nuru (Suleka Mathew).

Mallory: You’ve never seen this before, right?

Rohin: I have seen it once many years ago actually

so I know it has the line “HOW ABOUT A MIMOSA FOR MY SAMOSA”

Mallory: AHHH WE OPEN ON KYLE MACLACHLAN

BOLD MOVE

Rohin: he has aged a lot

Spicy

Priya Alika Elias is a lawyer who lives in Boston. She wrote about her penchant for spicy flavors and how that part of her identity has changed over time and how people have reacted to it.

I don’t have much of a sweet tooth, though Indian sweets deserve their own hall of fame. For dessert, like, my father, I eat tender green mangoes with salt and chilli powder. The taste is mouth-puckeringly sour. Between the two of us, we polish off every mango in the freezer without so much as a stomach-ache to show for it. My mother sighs when I drown my food in spices to make it extra hot, a trick I picked up from him.

Bend It Like Beckham: A Celebration

Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite wrote for The Toast about what the film Bend it Like Beckham means to her.

In 2003, things were changing for me. I started high school, bought my first pair of jeans that actually fit (flared, with the lowest rise possible), picked my favourite Beatle (John, but also George), and saw Bend it Like Beckham for the first time. All of these events were major milestones, but the last one has probably been the most influential to my life trajectory.

Bus Rides I Have Had

Dancer, Bollywood enthusiast, and collector of statement necklaces Nina Bhattacharya is currently completing her M.S. in Global Health and Population at Harvard. Ride along with her as she reflects on bus rides she’s taken in different countries.

I don’t think the conductor realized how much that small statement meant to me. This was my first time visiting India by myself, without family. While living in a village was great exposure to a kind of life I had never experienced, it was sometimes isolating and emotionally difficult. From the way I struggled to articulate nuanced thoughts in Hindi to how my foreignness created an invisible wall in even my closest relationships in the village, I felt perpetually uncertain in a lot of my interactions.

The Five Stages of Being Biracial (If You’re Me)

The Toast’s staff writer Jaya Saxena shared what growing up biracial means to her and how that changed over time as she was growing up.

My family did not act like other immigrant or biracial families. Those kids had parents who spoke of siblings and childhoods in foreign countries with thick accents. They always seemed to be returning to those countries, or filling their households with decorations and music to make it feel like they had never left. They had kids who actually knew something about a “home country.” My house never felt like Talia’s house, where she’d switch between speaking to her dad in Hebrew, her mom in English, and then playing Aladdin on Sega Genesis with me.

* * *

Pavani Yalamanchili is an editor at The Aerogram. Find her on Twitter at @_pavani, and follow The Aerogram at @theaerogram and on Facebook.