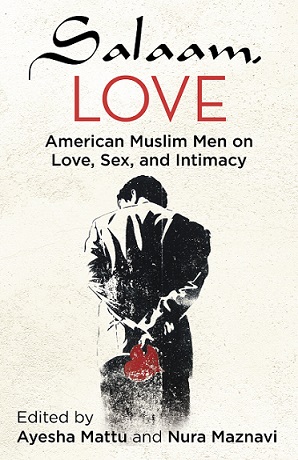

In Salaam, Love editors Ayesha Mattu and Nura Maznavi provide a space for American Muslim men to speak openly about their romantic lives, offering frank, funny, and insightful glimpses into their hearts — and bedrooms.

Writer Alykhan Boolani contributed “A Grown-Ass Man” to this collection. Boolani grew up in Berkeley, California. He was a high school history teacher in nearby Oakland for five years before his recent move to Brooklyn, New York, to help found a new school. He loves being a schoolteacher, and never ceases to be inspired by youth, with their uncanny abilities to resist dogma and mindfully labor toward their own truths — all with love and resilience. When not in the classroom, you can find Alykhan writing short stories, listening to Coltrane, or riding motorcycles with caution.

Excerpted from Salaam, Love: American Muslim Men on Love, Sex, and Intimacy edited by Ayesha Mattu and Nura Maznavi. Copyright 2014. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.

Terrified Immigrant Syndrome

I gave up trying to meet women at jamat khana years ago. These days, I’m mostly in it for the aunties, the uncles, and Bapa’s chai.

I haven’t given up on religion itself per se, but I’ve got my devotional disregard down to a science: Friday night dua starts at eight and is over by half past. At five till, I glance at my wrist, making note of the day and time. At ten past, I attempt to fix my hair in the mirror by my front door. North Oakland is a solid fifteen to Alameda, on the 24. By the time I slide into the corporate-office-park-unitcum-masjid—demarcated only by a yellowed inkjet printout of an American flag with the words UNITED WE STAND in Times New Roman—prayers are damn-near over and the first eyes on me are always Pops’s. He sits in the chairs by the door, outside the prayer hall, with all the other budha bhais, whose knees and backs keep them off the ground where the rest of us sit. He looks me up and down, looks at the clock, looks right back at me, and grins to himself while shaking his head. I choose to interpret this as playful disappointment.

Fortunately my mother sits inside, usually up front. I’m glad to know that she doesn’t have to witness my weekly ritual of cultivated neglect. We are, however, keenly aware of each other; and in the sad state of affairs, weekly neglect is far better than downright absence. Like a hostage situation, my attendance holds Ma’s last hope for my life on sirat al-Mustaqim by its throat. Otherwise, I could become like so-and-so Auntie’s kids who stopped coming altogether, and then became alcohol-and-drug addicts, and then married—gasp— the whites!

Unrestricted hyperbole is a well-documented effect of Terrified Immigrant Syndrome (TIS). Thus my mother links a bit of religious laxity to wholesale cultural downfall—another friend’s mother has been known to link Jolt Cola to eventual cocaine use. But admittedly, her fears are, if dramatic, not unfounded. Her central cultural wish of keeping Shia Imami Isma’ilism conjugal, in my sordid generation, is quickly becoming, outside of the motherland, a dream deferred.

I mean the story of Ma and Pops? It may as well be another dimension of space/time: the two grew up in flats opposite each other, on a street bookended by a grand Isma’ili jamat khana and an Isma’ili grammar school, in a part of Karachi where the cultural, economic, and social life was Isma’ili. It was not an arranged match, though a degree of city planning may have been involved.

The Mantra

The table, crowded by hot and slick plates, looks to be alive. The overhead fan cuts the fluorescents into a flicker, and the feast’s glistening seems to dance in the light. We’ve been eating like this every night since we arrived in Karachi, around a long wooden table protected by a thick plastic film. I gladly ignore grown-up conversation about family drama, focusing instead on stuffing my face with home cooking, smacking my lips a little too loudly. I feel almost mischievously young. Uncles, mothers, fathers, aunties, brothers, sisters, cousins—I pick up bits here and there, this chatter in the flutters of hometown Sindhi I can only half understand, not having grown up here.