Summer Camp Buddies

So I tell Paola everything.

I tell her about how I went to sleep on Friday reeling in the nuances of a date at once volitional and votive, strange and intimate. And how I slept soundly, grinning like a dope.

Then, a rude awakening: on a clear and bright Saturday morning— the morning after an outstanding first date—the unseasonable, the unpredictable, the damn near impossible for such a low altitude: the Avalanche.

A Saturday morning text message from ZARAH read: Heard you had a big date last night 😉 LOL.

With the speed afforded only by modern smartphone technology, I dialed my sister’s number with the kind of panicked instinct expressly reserved for autonomic processes. My mind caught up a half second later and I ended the call to assess: How? Who? Paola? No, impossible. Public place—spying? Allah?

I call back another minute later, and my sister answered the phone with a kind of elongated hey, stretched out extra long in that I-know-what-you-did-last-night kind of tone. I cursed at her immediately in a half-playful, half-sororicidal fashion, demanding truth and explanations.

The taqueria. They met in line. We had just talked about this specific taqueria, the night before—how I love it, how Sofiya loves it, how the whole fam loves it—did I put it in her head?

“Your friend happens to know Samir—they went to Al-Ummah together, in ’96.”

I was beyond belief. Zarah knew this, and I sensed she was graciously holding back her pleasure at my suffering. Isma’ili summer camp? Upstate New York? Fifteen years ago?

“What’s the damage?”

“Me, Samir—Pops was there, too. Don’t worry, we’ve already agreed not to tell Mom.”

She read my mind. This was bad enough. Definitely can’t tell Ma. Things were already turning for the worse. Telling Ma would introduce a wild card into an already fragile situation. The explosive potential energy of mentioning The Fabled Isma’ili Chokri could very well blow this whole thing apart.

On the phone with my sister still, the call-waiting screen popped up, reading SOFIYA. I took a deep breath, but not deep enough, and inadvertently answered with that same stupid hey my sister had just used.

Cosmic Kismet

So it’s not as bad I think: Zarah and Pops kept it cool, and apparently Samir, in a rare case of animation—brought on, perhaps, by fond camp memories—was a bit charming himself. The worst of it is in my head, as the soul search for The Meaning of All This commences: is this a simple coincidence? A cute cosmic joke? Foul play, or maybe conspiracy? More than anything, where can I find some privacy in the –ism? Is that even possible, or else, the point? I feel an acute sense of dread: the shrinking space of my formerly independent potential love-interest-type situation.

The coup de grâce a la Paola, of course, would become the-end- as-we-know-it of this hapless love, but it was truly the irony of Ma’s sense of spiritual-religious responsibility that set everything in motion toward an irrevocable end: a mundane Sunday closet-cleaning, a phone number found, remembrance of a promise, and a love-shattering phone call.

I imagine it sounded something like this:

“Hello, is this Sofiya? Ya Ali madad, darling, my name is Shamim Aunty, from Alameda jamat khana. How are you doing? . . .Good, beta. Well, Sofiya honey, I met your mother a few months ago . . . Yes, right, when she was visiting. She gave me your number and I’ve just now found it . . . I know, funny . . . Well, she said that you might need a reminder every now and again to come to jamat khana, and I promised her I would call you, so darling, you should really try to make it some Friday . . . Mmhmm, yes, I know . . . mmhmm . . . of course. You live where? Oh perfect! My son lives in Oakland, he has a car, his name is—”

Again, SOFIYA—a text this time—which reads, thirty-six hours after Friday night: I think your mother just called me.

Bapa’s Chai

Navroz always packs the house—a fire hazard of a Persian New Year celebration, where 130 murids squeeze into the tiny officepark- cum-masjid, capacity 70. I know she’ll be there, and I consider joining Samir in the parking lot to sit this one out. We hadn’t spoken in weeks, vis-a-vis my precipitous drop off the planet. Just thinking about the bullshit sincerity of the clichéd excuse—I’m just not in that place right now, or You’re just too good, or the immortal I don’t want to get attached—was making me sick with anxiety. To lie so unabashedly, and to cloak it in earnestness: it seems almost sacrilegious to wield such dunya banalities in a place so expressly concerned with cultivating a healthy sense of deen.

She’s standing right by Bapa’s percolator, and moving in this time elicits no familial Avalanche (their absence most likely spurred by a fiery tirade at the dinner table on the topic of “Minding One’s Own Business,” by Yours Truly). We get some air outside, the steam of our chais rising from Styrofoam cups into the cool March night. Behind the strained, excruciatingly robotic small talk, Sofiya’s eyes are calling: So are you going to say it, or am I?

I want to say it all, I want to paint a picture of my mental landscape so vivid that it would surely rescue me from my current (presumed) status as Another Asshole Who Didn’t Call. I want to tell her about how I can’t deal with the ways in which the –ism looms so large. That I want to stand up from prostration and speak directly into the big, scary face of Tradition, and say, Hey, bow toward me a little bit, like I bow toward you! Just give me some room, and I’ll do this my way, and I’ll do it with good heart and a right mind, like you taught me! But is this really a conversation to have with an institution? Or is it a really about my mother? As in Ma, I love you, but I’m a grown-ass man and you can’t play a major part in my love life, albeit by utter cosmic accident.

So I don’t: I don’t say any of it. My heart and mind go cold like this chai in my hands, and I spout off some spurious excuse-for-an-excuse that impresses no one and leaves both of us feeling ashamed and sad.

I slink back through the front door of the office-park-cum-masjid, into the warmth of bodies created by endless uncles and aunties standing too close to one another; into the warmth of knowing that Ma and Pops and Zarah and Samir—abashed and perhaps afraid of me for tonight—linger somewhere out of my line of sight; into the warmth of Bapa’s gaze, who signals to me, sticks his finger into my cold chai, shoots me an indignant glance before he dumps it out, and pours me a hot, fresh cup.

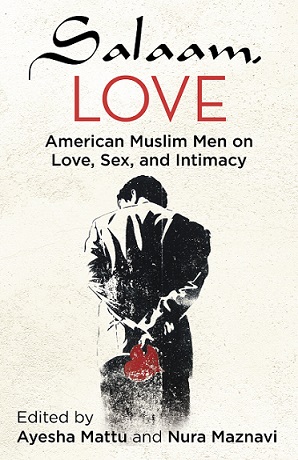

Excerpted from Salaam, Love: American Muslim Men on Love, Sex, and Intimacy edited by Ayesha Mattu and Nura Maznavi. Copyright 2014. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.