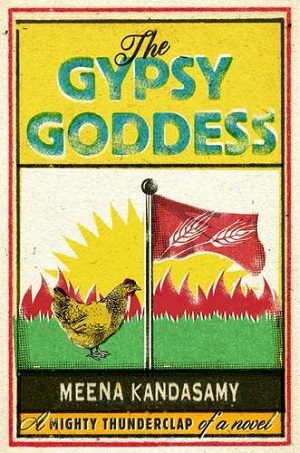

How do you tell the story of a disaster? Poet, activist, and first-time novelist Meena Kandasamy approaches this difficult question in The Gypsy Goddess. A fractured narrative that takes place in Kilvenmani, Tamil Nadu, the novel centers on the real-life 1968 massacre of 44 Dalit agricultural laborers. Very simply, it portrays the fatal results of abused workers convinced by Marxist Party leaders to strike for better working conditions from their landlord. More complexly, the novel takes on tangled questions of caste, class, and the churning machine of the Green Revolution and global capitalism in mid-century India. Kandasamy follows in the footsteps of Bengali author Mahasweta Devi — who has been translated and theorized by the formidable scholar of comparative literature and Subaltern Studies, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak — in the novel’s dedication to representing and giving voice to a brutalized Dalit population.

How do you tell the story of a disaster? Poet, activist, and first-time novelist Meena Kandasamy approaches this difficult question in The Gypsy Goddess. A fractured narrative that takes place in Kilvenmani, Tamil Nadu, the novel centers on the real-life 1968 massacre of 44 Dalit agricultural laborers. Very simply, it portrays the fatal results of abused workers convinced by Marxist Party leaders to strike for better working conditions from their landlord. More complexly, the novel takes on tangled questions of caste, class, and the churning machine of the Green Revolution and global capitalism in mid-century India. Kandasamy follows in the footsteps of Bengali author Mahasweta Devi — who has been translated and theorized by the formidable scholar of comparative literature and Subaltern Studies, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak — in the novel’s dedication to representing and giving voice to a brutalized Dalit population.

But before we hear the voices of the oppressed and terrorized workers, before we read of their beatings and burnings, before, indeed, we hear the voices of the landlords and Marxist party leaders who equally subject this group of workers to unimaginable exploitation and violence, Kandasamy presents us with the strong voice of the narrator herself. Self-reflective to the point of exhaustion, the first sections of the book position the author and novel among every possible sort of readership and reception. This lends The Gypsy Goddess a distinct tone of anxiousness, if not defensiveness or full-on combativeness. “Are you still hunting around for the one-line synopsis and the sixty-second sound bite?” the narrator questions archly. “Do you want me to compress this tragedy to fit into Twitter? How does one even enter this heart of darkness?”

The narrator seems to have arrived in her own novel spoiling for a fight. But with whom? The reader? The publishing industry? Social media? Often in this first chapter, entitled “Background,” she takes on the academy directly, expounding on the efforts of a “left-leaning Professor” who did fieldwork in Tamil Nadu. “If only I could get all of you to read her work, familiarize yourself with Marxist theory and take in all the information tucked away in the footnotes, I would have no need to write this novel. Sadly, you are too lazy for research papers.” At other points, the narrator quotes Slavoj Zizek, dismisses “Derrida-Schmerrida,” and compares herself to Zora Neale Hurston and Nicki Minaj. Needless to say, a dedicated reader of The Gypsy Goddess must have a thick skin and a patient eye. Kandasamy’s writing seems to follow the Marxist methodology of early twentieth-century playwright Bertolt Brecht, in which efforts to alienate readers shake us out of our complicity (and our jelly-boned desire for a “good story”) and whip us into alertness, and hopefully, action.

In the whirl of her prose, we are never able to gain sure footing, and this is deliberate on Kandasamy’s part.

In the second part of the novel, Kandasamy’s rhetorical grandstanding and throat-clearing give way to breathtaking and disturbing passages that depict the gruesomeness of the event itself. In the whirl of her prose, we are never able to gain sure footing, and this is deliberate on Kandasamy’s part. At its heart The Gypsy Goddess is a novel about the difficulty of storytelling. It is a work that meditates on the impossibility of rendering into words the atrocity of a brutal massacre. The seeming hostility of Kandasamy’s opening chapters belies the sheer exertion of the task she takes on, which is the problem of how to write ethically about an unspeakable act of human violence. The constant negotiation between academic writing, journalism, tweeting, and poetry is a way of circling around this question: what is the best way to tell the story of 44 wretched souls who were hacked and charred alive for merely striking in the name of humane working conditions? Is it more ethical to make this a news story, a scholarly text, or a work of art? Is there any way to represent this disaster, which is at the explosive intersection of caste, class, capitalist, and environmental oppression, without doing the solemnness of the horrific tragedy itself a disservice?

As The Gypsy Goddess proceeds, the loud and hostile voice of the narrator breaks apart into the many fragmented perspectives of the workers and landlords and Marxist party leaders in a disorienting procession that mimics, perhaps, the confusing regulations, empty promises, and harsh working conditions forced upon the Kilvenmani laborers. The narration changes from a first person singular, to a first person plural, to a second person — there is an “I”, there is a “we,” there is a “you,” but we are never quite sure who these pronouns address. At the very center of The Gypsy Goddess is a scene of an inspector walking through the field of incinerated bodies. His task is to “comment on the expression of countenance and the position of limbs, and report the presence of blood (liquid or clotted), saliva, froth, vomit, or semen at the scene of the crime.” What follows is a numbered list that spares no details of the individual remains of the victims, in precise police-procedural diction.

What is the best way to tell the story of 44 wretched souls who were hacked and charred alive for merely striking in the name of humane working conditions?

Contrasting the coldness of this litany is the spectacular violence of the massacre itself. In a section entitled, “Burial Ground,” the novel moves into the nightmarish (yet still dreamlike) perspective of the burning victims. Kandasamy’s poetic writing takes flight here as she shakes off the tethers and hang-ups of her academic and publishing-house interlocutors.

Women carelessly wind the fire around their hips and across their bare breasts. Girls carry fire in the ends of their curling hair and they pretend not to notice at all. Men swallow the fire as if their stomachs were stoves. Children catch fire when they run because the wind shaves their skin and sets them alight. The air is full of golden fire-dust. Everything is ablaze.

Everyone is glowing.

In such surreal scenes the answers to Kandasamy’s many combative questions about medium, form, audience, and ethics in storytelling become clear. Far from alienating, these gorgeous, gut-and-heart wrenching paragraphs captivate and devastate. The Gypsy Goddess is a novel that vehemently resists the novelistic form (as well as the scholastic, journalistic, and tweeting form). But in these profoundly poetic passages, Kandasamy’s language shines and the urgency of the Kilvenmani massacre roils in the blood of her reader. We cannot look away, and indeed we should not. Kandasamy’s language borders on the sublime when she transitions into a perspective that is impossible to imagine on a human scale: that of the immolated. This is writing from outside the human experience, a tale no one lives to tell — the very substance of inhumanity. And it is here that Kandasamy, with the full force of her poetic skill, “enters the heart of darkness.”

Nasia Anam is a doctoral candidate in Comparative Literature at UCLA. Her dissertation project is on novels of South Asian and North African immigration in postwar London and Paris. She lives in Los Angeles.