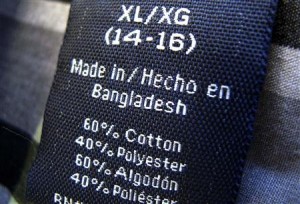

In the wake of the tragic April 24 factory collapse in Bangladesh, the garment industry has come under fire for lax safety standards and weak protection of workers’ rights. These criticisms are obviously valid, given the horrific scale of the catastrophe: 1,127 people dead, some 2,500 injured, and a “trail of shattered lives,” as the Guardian recently put it. Look at Pakhi Begum, a 25-year-old mother of two who lost both her legs in the collapse, and you’ll never want to buy a shirt labeled “Made in Bangladesh” ever again.

Before we punitively limit trade will garment factories in developing countries, however, here’s one counterintuitive idea to consider: In some twisted kind of way, these factories are advancing the status of women in traditionally patriarchal societies. Kimberly Elliott of the poverty-fighting Center for Global Development told the Washington Post, “Cutting off trade doesn’t help anything. They lose 3 to 4 million jobs mostly held by young women who would otherwise be working on farms or having kids as teenagers.”

Before we punitively limit trade will garment factories in developing countries, however, here’s one counterintuitive idea to consider: In some twisted kind of way, these factories are advancing the status of women in traditionally patriarchal societies. Kimberly Elliott of the poverty-fighting Center for Global Development told the Washington Post, “Cutting off trade doesn’t help anything. They lose 3 to 4 million jobs mostly held by young women who would otherwise be working on farms or having kids as teenagers.”

The garment industry has drawn unprecedented numbers of young women into the workforce. These women are empowered by earning their own money; they also delay marriage and childbirth — all in a traditionally male-dominated culture. The factories are also linked to higher rates of Bangladeshi girls going to school, according to illuminating research by Yale University economist Mushfiq Mobarak and University of Washington colleague Rachel Heath. “It has benefited women in a powerful way,” Raymond Offenheiser, president of Oxfam America and formerly the Ford Foundation’s representative in Bangladesh, told the Post.

Despite the pitiful wages and often dangerous working conditions, women are flocking to these jobs because they offer something the desperately poor need in order to break the cycle of poverty: a steady paycheck. As Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo explain in their book, “Poor Economics,” a steady, predictable income stream means your child will be more readily accepted into a school, a hospital will be more likely to give you an expensive treatment, and you’ll find it easier to get credit to invest in your home or other family member’s business. As Pietra Rivoli, author of “The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy,” told Bloomberg, Bangladesh is “still a desperately poor country, and we shouldn’t minimize what a steady job with a steady paycheck means to a poor woman.”

Of course, none of this means anyone should have to risk her life working in a dangerous factory. Westerners should name and shame companies that work with shady suppliers, and importing countries’ governments should push nations such as Bangladesh to enforce safety codes and labor laws.

Let’s not forget, though, that when women are escaping teen motherhood and earning money — even in terrible working conditions — it shifts their bargaining power within the family, and taka by taka, cultural change happens.

Preeti Aroon, a writer based in Washington, D.C., is copy chief at Foreign Policy magazine and tweets at @pjaroonFP.