“It’s amazing how such small objects can contain so many emotions, memories and aspirations of the person possessing them,” says Puja Bhargava Kamath of the Indian Jewellery Project.

As most women probably have a few pieces of jewelry in their possession which mean the world to them, they’ll probably identify with that statement.

Kamath is an apt person to speak about all matters jewelry related. In addition to being the brains behind the Indian Jewellery project (which she says was inspired by the Indian Memory Project), she also has her own brand, Lai, which sells hand-crafted silver jewelry. A graduate of India’s National Institute of Fashion and Technology, she currently lives in California’s Bay Area.

We talked to Kamath about discovering the stories behind the jewels and her quest to document India’s jewelry heritage:

What does jewelry personally mean to you? What do you especially enjoy about working with jewelry?

I’ve always loved jewelry and strongly believe in the power of a striking piece of jewelry dramatically elevating and defining an outfit or look. I also feel that just as someone’s book collection is very reflective of their personality and where they are coming from, the jewelry collection of a woman is equally telling of her journey in life and the person that she is.

I love the miniature scale and detailing that is involved in creating a jewelry piece. My favorite part of designing jewelry though involves immersing myself in research: I love it when I can learn something about, say, the weaving a particular region specializes in and re-interpreting it through my jewelry designs. Our brand is not just about aesthetically pleasing jewelry: it also has a story to tell.

What led to the inception of the Indian Jewelry Project? What are you striving to achieve through the project?

I came across the Indian Memory Project a few months ago and fell in love with it. It struck me that it would be wonderful if an open archive like that also existed for Indian jewelry; I was particularly interested in following it up as jewelry is my current area of work and focus.

I also felt that the project would be viable as people have access to vintage family photographs, with family members often wearing jewelry in them, in addition to possessing the actual heirloom pieces themselves.

In short, it aims to be a crowd-sourced visual history of Indian jewelry through the personal archives of families. We invite people to comb through their old family albums and contribute pictures with emphasis on jewelry worn in them; we are also accepting photographs of family heirloom jewelry as shot in present time.

There is no final destination for IJP as of yet; with time, we hope it will become a substantial and valuable jewelry archive, credible source of socio-historical reference as well as providing aesthetic, visual, and design inspiration. Our current focus is to raise awareness about the project and encourage people to send in their submissions.

You mention that it is a crowd-sourced project. How did you raise awareness and what has the response been like?

I began by reaching out to the community of jewelry lovers that we have cultivated via Lai. Selected media persons and bloggers have also shown interest in the project and covered it. I hope that we will see increased awareness amongst people and encourage them to particulate in the project. We are still only three months old though and so our journey has just begun: we do need more submissions though to keep the project relevant and engaging for those following it.

Can you recount any particularly memorable jewelry stories that you have received?

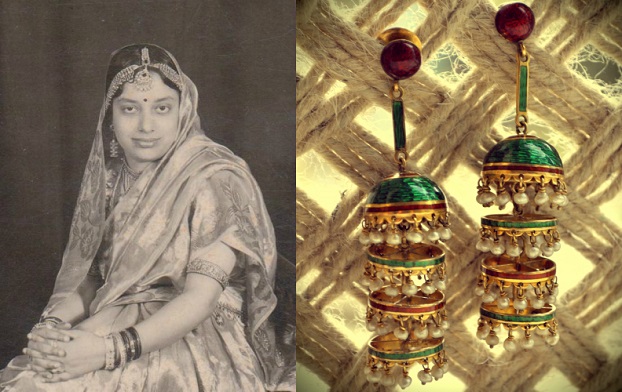

One contributor submitted a photograph of her maternal grandmother wearing amongst several pieces of jewelry four-tiered jhumkas [type of earrings]) and gold kadas [thick bangles], mentioning that these two items have been passed down to her. She also highlighted the fact that it was her grandfather who had taken this picture.

Another is of a photograph of a white stone set in a gold band; the story contributor, a 93-year-old gentleman from Bangalore narrated that during the 1970s, he had purchased 30 grams of gold for his daughter’s wedding; having discovered few grams of unused gold, he decided to treat himself to a ring — and even witnessed the making of the ring at a gold-smith’s shop in Bangarpet, Kolar district, Karnataka, which was famous for gold-mining. “The whole process was enjoyable to watch and the ring was ready to wear in ten hours — and even to this day, I enjoy wearing the ring!” he says in his story.

Do you plan to expand IJP into a website? What other future plans do you have for the project?

If we manage to amass a large enough number of submissions, we will then definitely consider creating a website exclusively dedicated to it. We could standardize the pictures’ presentation, perhaps having them professionally re-photographed and then, later, launch a beautiful photo-book documenting these jewelry photo-stories. Another idea is to come out with an IJP-inspired jewelry collection.

We have a gut instinct that we are on our way to creating a project which people will definitely love to be part of.

Visit the IJP and Lai Facebook pages or IJP on Pinterest, for more details.

Priyanka Sacheti is an independent cultural writer living in Pittsburgh. Her work has been featured in Gulf News, Khaleejesque, and Brownbook. When she’s not busy working on a collection of short stories or Instagramming, she blogs at I Am Just a Visual Person and Photo Kahanis. She tweets at @priyankasacheti.