Before I begin this review, a moment of indulgent transparency: Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding is my favorite film (topping a list of otherwise action and science-fiction movies of the last 20 years). The 2001 film, about a middle-class Delhi family coming together for nuptials and the ensuing relationships that are torn and kindled, is the closest I’ve ever seen to having my own life captured on screen, save for one critical difference — I grew up in America, with all the contemporary diasporic hybrid trappings.

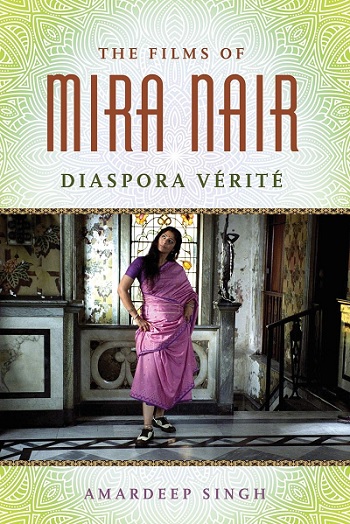

I bring this up is because it is emblematic of why Amardeep Singh’s new book, The Films of Mira Nair: Diaspora Vérité (University Press of Mississippi, October 15, 2018) is an important and successful volume not just to academic literary studies, but to contextualizing Nair as an integral artistic voice and force for the global South Asian identity. Monsoon Wedding was, by her own words, “a Bollywood film on my own terms,” but moreover, it’s less a Bollywood film than a movie about people who watch Bollywood.

Singh’s book, surprisingly is the first such comprehensive academic study of Nair’s nearly 40-year career since her first documentary, Jama Masjid Street Journal, to her most recent Queen of Katwe, observing intersecting threads of diaspora, feminism, and documentary influences across a body of work that has covered characters and stories, actors, class, and continents. Nair’s ability to circle back to these themes in films that differ widely in terms of genre, style, budget and marketing has created a body rich with small nuances in the larger story.

“What becomes clear throughout the book is that while Nair’s films are not autobiographical, they are informed by the inherent exigencies of her own life.”

What becomes clear throughout the book is that while Nair’s films are not autobiographical, they are informed by the inherent exigencies of her own life. Singh opts not to review her filmography in strict chronological order, nor cluster films by subject matter, as Nair frequently circles around and back to stories and material that hit upon the same themes, often attuning or adapting scripts to suit her auteur desires.

Thus, we open on a chapter discussing her initial documentaries and move on to one on her feature debut, 1988’s Salaam Bombay!, which roots the overall analysis in Nair’s own deference to European cinema vérité and neorealist styles. But Singh then cuts ahead to 2001’s Monsoon, connecting again to the deft cinematic style, but also to Bombay’s commentary on Bollywood dreams and the darker truths of life in modernizing India.

As a casual viewer, I’ve always been curious why Nair’s filmography seems almost-lackadaisical floating from whatever projects come her way. Why, for example, did the raw kinetic energy of her initial films give way to the lush literary adaptations like The Namesake (2006) and The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2012)?

* * *

In my first viewing of Monsoon Wedding, it fell flat. In the large cast, no single arc felt fulfilled, and the tender sweeping love stories felt dissonant with the darker side plot of child abuse. Similarly, Nair has been criticized for her often unsubtle impositions on the work, whether it’s narrating and appearing in her earlier documentaries, or emphasizing the Indian sections from William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, or re-calibrating Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake to focus more on the parent’s stories. As popular entertainments, they offset her films’ narrative fidelity.

“Though the films look glossier and feature higher profile actors as time goes on, there is a continuous, keen interest in the human moments of displacement.”

There is discussion of film craft and form when relevant to his arguments, but Singh approaches this as a comparative literary critic. Though the films look glossier and feature higher profile actors as time goes on, there is a continuous, keen interest in the human moments of displacement. As given in the title, Singh’s key focus is examining how Nair’s verité influences consistently bring her just outside the frame.

Through Singh’s lens, those narrative “flaws” become bearers of Nair’s strengths as a vérité filmmaker: nudging and supporting the human subjects in the story to give proper context and voice where other filmmakers may not be so sympathetic, and given the often controversial, or unmarketable backdrops of those films — the book affirms just how valuable her work is, when taken as a whole body.

“Through Singh’s lens, those narrative “flaws” become bearers of Nair’s strengths as a vérité filmmaker…”

The book is extensively researched, pointing interested readers to other scholars who have also dug into the director’s filmography and tried to put it in context of her contemporaries. Singh does a service here, by putting Mira Nair in context with Mira Nair. He gives us a portrait of an artist who grows with each film, often wrestling with her own multinational creative space. They feel as a fabric of one work.

Highlights are discussions of the actors workshop for the non-professional child cast of Salaam Bombay!, the mise-en-scène comparison of Monsoon’s “Chunari Chunari” number to the one in its originating film Biwi No. 1, or Mississippi Masala’s intentionally-cringeworthy scene where an Indian-American supporting character panders to the African-American lead. Each show the attempts by Nair to bridge worlds through film, both in craft and content.

“The book contends that Nair, working on her own terms, making stories which appeal to her, no matter where and how the funding comes from, has put her career in occasional constraints…”

The book contends that Nair, working on her own terms, making stories which appeal to her, no matter where and how the funding comes from, has put her career in occasional constraints, — India’s censors forced hard cuts onto Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love, while no one in the U.S. would touch a story that asks us to sympathize with a Pakistani who rejects America after 9/11.

In doing so, Singh is able to abstract keen observations about how time and again, her characters share qualities of shifting across political borders, social classes, domestic spaces, ethnic identities. Chapter after chapter he shows how still, over so many decades, they remain prickly subjects, and Nair continues to find new ways to explore them.

These are films made for an audience, if not everyone, and Diaspora Vérité not only further solidifies Nair’s filmography in an academic canon, but gives the film viewer new tools to reassess the films which, though sometimes not completely fulfilling cinematic works, can now be seen richly imbued with idiosyncratic scenes, lines, and moments that are impactful political and social mirrors for her communities.

It took a couple more viewings, and perhaps my own maturation in thinking about those issues, to see this in Monsoon. Singh’s book also gives us a language to talk about it.

* * *

Aditya Desai lives in Baltimore, currently teaching writing and revising a couple novels that he keeps threatening to finish someday. He received his MFA in Fiction from the University of Maryland, College Park. His stories, essays, and poems have appeared in B O D Y, The Rumpus, The Millions, The Margins, District Lit, The Kartika Review, CultureStrike, and others, which you can find most of at adityadesaiwriter.com. Find him on Twitter @atwittya.