I’ve read two roundups (here and here) of the spectacle that was the 2018 Jaipur Literature Festival (Jan. 24-28), plus avidly followed the hilarious Twitter handle, JLFInsider, and there was so little overlap that one might imagine everyone had gone to different festivals. That’s sort of the beauty and overwhelmingness of JLF, billed as the greatest literary show on earth.

It’s certainly the largest: more than a quarter million visitors show up every year. There are half a dozen stages set up across the grounds of Diggi Palace, and from 10am til 6pm for five days straight, you can get your literature on (and sometimes your Bollywood too).

“I think the best writers stride across genres.” – Prayaag Akbar, author of Leila

This was my second time at JLF as a speaker, and I love how there’s this small part of my life where I feel like royalty, and it’s not just because every night, there’s a different party and performance at a different palace or majestic fort in Jaipur. It’s also because despite the various hierarchies of author importance, once you’re in Jaipur, everyone gets a seat at the table, meaning literally a scrumptious spread of food and wine at every meal, plus lux accommodations for the duration. They’ve also ironed out some kinks this year, and so plus ones (or Speaker Companions, as JLF calls them) have hassle-free access to lounges and meals and evening performances.

“The sun was for everyone.” – Adriana Lisboa, author of Crow Blue

I was on three panels this year at JLF. First up was a poetry panel on Saturday, January 27, 2018, which featured readings in Bangla, English, Hindi, and Welsh by poets Devyani Bhardwaj, Eurig Salisbury, Makarand Paranjape, Sampurna Chattarji, Sangeeta Gupta, Sudipti, and me, moderated by Mohini Gupta. As per the geographies of my memoir, Olive Witch, I read three poems, set in Nigeria (the Python), Bangladesh (the Freedom Fighter), and the States (City of Queens). It was a vibrant session, although poets: I know we’re never given as much shrift as the prosers, but could we not use that as license to go over our allotted times? Thankfully, the audience still seemed to be paying attention even when I went on last, around the hour mark.

“How does fiction ever compete with fact? Poetry is the news that stays news.” – Jeet Thayil, author of Narcopolis

My second panel was on Sunday, January 28, 2018, called The Feminine Gaze: Women Writing Memoir. It featured four women who had recently published memoirs: Alia Malek, Amy Tan, Juliet Nicolson, and me in conversation with Keggie Carew, who despite stepping in last minute, did a thorough and thoughtful job.

“I don’t think everyone can master the form of the nonfiction novel.” – Kaya Genç, author of Under the Shadows

My fellow panelists had slightly less knee-jerk responses than I did to our session name. My thought was that if there were all men on the panel, the so-called manel, you can be damn sure they wouldn’t be calling it The Male Gaze: Men Writing Memoir, and there’s a time and place for affirmative action, and we need it more than ever in this misogynist world of ours, but a festival of Jaipur’s stature doesn’t need to pigeon-hole women.

Ok <end of rant> because aside from naming controversies, the panel was fantastic. I just finished reading Syrian journalist and human rights lawyer Alia Malek’s compelling mash-up of political history and memoir, interleaving Syria’s history with that of her own family: The Home That Was Our Country. It was an education that is ever more resonant in today’s world of displacement, fascism, and loss.

“I know enough to know what I don’t know.” – Alia Malek, author of The Home That Was Our Country

Juliet Nicolson spoke movingly about the events and people that inspired her memoir, A House Full of Daughters, which tells the story of seven generations of women in her family, spanning Europe, the UK, and the US, with themes of abandonment, loneliness, alcoholism, and belonging.

“I saw my mother die of alcoholism and admitting to my own problem in my book was sort of a way to show her that I forgive her for being absent.” – Juliet Nicolson, author of A House Full of Daughters

And Amy Tan needs little introduction as she was one of the star authors at JLF this year. She’s taken a break from her bountiful fiction accomplishments, and recently published a memoir called Where the Past Begins. It’s a loose collection of “cantos” on creativity, the act of writing, the relationship between mothers and daughters, and editors and writers, childhood trauma, and what it means to reconstruct family history.

“I don’t read reviews, good or bad. It’s a reflection of what someone else thinks of you and your work. If you believe the good ones, you have to believe the bad ones. It can be harmful to you, destructive.” – Amy Tan, author of Where the Past Begins

My last speaker event was a panel called the Afropolitans (another name that comes with a little baggage) on Monday, January 29, 2018. I volunteered to moderate this one as it would spur me to add more African writers to my reading list and I was so glad I did because what a crew of rising literary stars: British Somalian novelist, Nadifa Mohamed, and (because Nigeria always takes over any gathering) two Nigerian writers: Abubakar Adam Ibrahim and Chika Unigwe.

I’m a huge fan of Chika’s, having read and reviewed her work before, although this was my first time meeting her in person (she is as stylish as she is talented). Her second novel, On Black Sisters Street, is the heart breaking story of four African sex workers in Antwerp, Belgium – the kind of story you may never hear, even less likely in literary form. Abubakar’s debut novel, Season of Crimson Blossoms, is a vividly described taboo-breaking story of an affair set in northern Nigeria with a cast of female dominated characters. Nadifa’s second novel, The Orchard of Lost Souls, is a gorgeous and harrowing story of Somalia’s civil war as seen through the eyes of three very different women.

We started off the discussion by talking about the word Afropolitans, which was originally constructed from the word Africa and the Greek word for citizen (polis), and was an attempt to emphasize the ordinary citizen’s experience in Africa. The term was popularized in an essay by Taiye Selasi which described Afropolitans as having hip urban lives with international careers. I like the original definition — focusing on the experiences of ordinary citizens. And when looking at literature with this frame, I thought it was quite relevant for all three authors on the panel.

All three of the books I mentioned have female protagonists. Chika is a Nigerian who started her writing career in Belgium, and she credits deep curiosity and a little bit of courage for venturing into the red-light district in Antwerp to talk to the women who worked there. Some of them looked very much like her, and many didn’t believe that she was who she said she was, an educated writer married to a Belgian and researching a book.

“This is me reversing that power. I’m going to write in English, but I’m writing Igbo in English. I’m not going to be able to colonise some island, so I’m going to colonise that language when I write.” – Chika Unigwe, author of On Black Sisters Street

The protagonist in Abubakar’s novel is an older Muslim widow who has a joyously erotic affair with a young thief, an unusual turn of events especially in the context of a conservative Northern Nigerian Muslim society which judges and condemns her at every turn. I loved that despite the taboo nature and a sense of doom, she’s given space to experience joy and release and love. Abubakar wanted to show how life can be for people in his hometown of Jos, but he also spent time re-imagining the city to include places like San Siro, the half constructed neighborhood that small time thieves and stoners use as their grey market home.

“What makes a story yours is you write it. If you don’t, it’s someone else’s.” – Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, author of Season of Crimson Blossoms

And Nadifa’s second novel shows the breakdown of Somalian civil society and the onset of civil war, as seen through the eyes of a young girl, an older woman, and a soldier. I was especially taken with how precisely and sensitively the trials and tribulations of older women were portrayed, in both bodily and societal ways. I think you can measure a society’s progress by how it treats its women and its marginalized communities. She talked about how her first novel, Black Mambo Boy, was about men and boys and being masculine, and she wanted to tell a story about Somalia’s collapse as lived through by women.

“I’m not reading history for war or the generals. I’m reading for stories of the ordinary citizens.” – Nadifa Mohamed, author of The Orchard of Lost Souls

We also talked about how language played a role in each author’s work. I’m not talking of that often-tiresome question of why one writes in English, but how each author used indigenous language and phrases in the text, as well as translated proverbs. There was no glossary in the back of any of the books, and sometimes it was not obvious from context what a word might mean. I loved this – that as readers, we would eventually get used to read other languages mixed in with English, that even if we didn’t understand everything, that might be ok.

For example, in Chika’s novel, On Black Sisters Street, there’s this line: “I liked the look of the woman. Ugly. Ojoka, but in a very attractive way.”

Or in Nadifa’s novel, The Orchard of Lost Souls, “her pale pink didic lights up in the sunlight, engulfing her body like a flower bud.”

Or any one of the fascinating proverbs that begin each of Abubakar’s chapters in Season of Crimson Blossoms: “A snail will never claim to have horns where rams are gathered.”

I had a great time talking to all three authors and hearing about some of the nuts and bolts behind the craft of their novels as well as what inspires them.

“Write 500 words a day. And at some point, walk on the grass.” – Michael Ondaatje

Of the other panels I attended as an audience member, the most star-studded session was Adaptations with Amy Tan, Michael Ondaatje, Mira Nair, Nicholas Shakespeare, and Tom Stoppard, in conversation with publisher Chiki Sarkar.

“Maybe adaptation is not the right word for making a book into a film. It’s not a direct mirrored reflection. The original story is perhaps like the light of a distant sun.’ – Chiki Sarkar

In a way, it didn’t matter what the panel was about because everyone was so eloquent that every line sounded like a pull quote. I found Michael Ondaatje and Tom Stoppard’s comments to be particularly generous and self-effacing.

“They all disappoint. They all have some shortfall.” – Tom Stoppard on adapting books to film

I had heard Mira Nair speak earlier in the month at the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival. In Jaipur, she was her same warm and inviting self with engaging anecdotes about filmmaking and adapting stories.

“You could have practically nothing, half a body, but you could still have flair. This man was what in Kamapla we call a Lifeist.” – Mira Nair on filming The Namesake.

There were a series of panels which seemed replicas of each other, including a panel on new writing, one on the art of the novel, another on reinventing the novel, and a fourth called the empire writes back. This might have been just fine if there had been completely different authors on stage for each session, but as it was, there was a lot of overlap. Of course, they’re writers and can talk about any number of topics from different angles, so it was ok, but I’d have liked to see some other faces on stage. I did enjoy learning about Charmaine Craig’s second novel, Miss Burma, which draws on the author’s family history to tell a story of contemporary Myanmar’s political upheavals.

“Auto fiction comes out of the tyranny of the self we see in social media.” – Charmaine Craig, author of Miss Burma

My personal highlight was listening to the grumpily hilarious Rabih Alameddine, a Lebanese American writer and painter whose every line dripped with cynicism and humour, a kind of modern day Oscar Wilde.

“If truth were important, we would not have elected Trump.” – Rabih Alameddine, author of The Angel of History

I loved the rousing session, Banned in India, with Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, Mridula Garg, and Paro Anand in conversation with the always brilliant Salil Tripathi. I’ve been following Hansda’s work since I met him at the Goa Arts and Literature Festival two years ago and was shocked and saddened when his new luscious collection of stories, The Adivasi Will Not Dance, was banned and he himself targeted. Upon being asked whether various censorships and threats had affected their work or motivation, all three authors emphatically said no! I’m not that brave, but I’m so glad they are.

“I am going to keep on writing.” – Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, author of The Adivasi Will Not Dance

![Han Yujoo, Adriana Lisboa, Kathy Reichs, Josefine Klougart, Leonora Miano, [translator], Tara June Winch, and Radha Chakravarty](http://theaerogram.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/jaipur6-1024x768.jpg)

“She had a face that only smiled in photographs.” – Tara June Winch, author of After the Carnage

I also attended a lively book session which paired two very different debut novels, one by Preti Taneja, who wrote We That Are Young, about social injustice in contemporary India based on Shakespeare’s King Lear, and one by Prayaag Akbar, who wrote Leila, a dystopian lens on cities and relationships and loss. After all the panels chock-full with people, it was nice just to have two authors on stage talking about their work (moderated ably by Mohini Gupta).

“I think women know this, that people are only too happy to explain things to you.” – Preti Taneja, author of We That Are Young

Also on stage (mostly) by herself was Tishani Doshi launching her book. Tishani has paired the presentation of her new poetry collection, Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods, with a slow sensate dance she performs while her voice recites a poem over the speaker overlain with music. She’s a poet, essayist, novelist, short story writer, and a dancer, and I love that she often combines these genres, and has now layered it with dance.

“I will fade backwards into the future and tell you what I see.”– Tishani Doshi, author of Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods

The Writing the Arab World panel was a passionate and powerful conversation, irritating audience questions notwithstanding. I had seen Alia Malek and Rabih Alameddine on other panels, but it was my first introduction to Iraqi-Dutch writer Rodaan Al-Galidi (who writes poetry and prose in Dutch which he taught himself) and Palestinian American writer and activist Susan Abulhawa (author of The Blue Between Sky and Water).

“I’m expected to represent Lebanon, to represent Arabic. I can barely represent me.” – Rabih Alameddine, author of The Angel of History

Amitava Kumar and Manu Joseph had a light-hearted book session poking fun at each other and themselves, while ostensibly discussing their new novels. And the last panel I attended was the inanely titled closing debate, #MeToo: Do Men Still Have It Too Easy, with Bee Rowlatt, Manu Joseph, Pinky Anand, Ruchira Gupta, Sandip Roy, and Vinod Dua, moderated by Namita Bhandare. There doesn’t seem to be a video of the session, but I think Bee Rowlatt summed it up in her opening salvo: “Duh.”

The debate did give me the chance to listen to sex trafficking abolitionist and journalist Ruchira Gupta passionately expounding on the state of women’s rights, as well as writer and journalist Sandip Roy’s pointed treatise on sexual harassment in journalism. I initially appreciated solicitor general and politician Pinky Anand’s sedate lawyerly style of speaking, but she lost me when she brought up the Mahmood Farooqui case, a massive miscarriage of justice and a crushing step backwards by not believing women and upholding rape culture. Thank goodness Ruchira spoke up to remind her and everyone else that the survivor said no, and “feeble” or not, no means no. Would that the Indian justice system, and the rest of the world, listen.

“Do you think the world is bored of men? I am.” – Manu Joseph, author of Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous

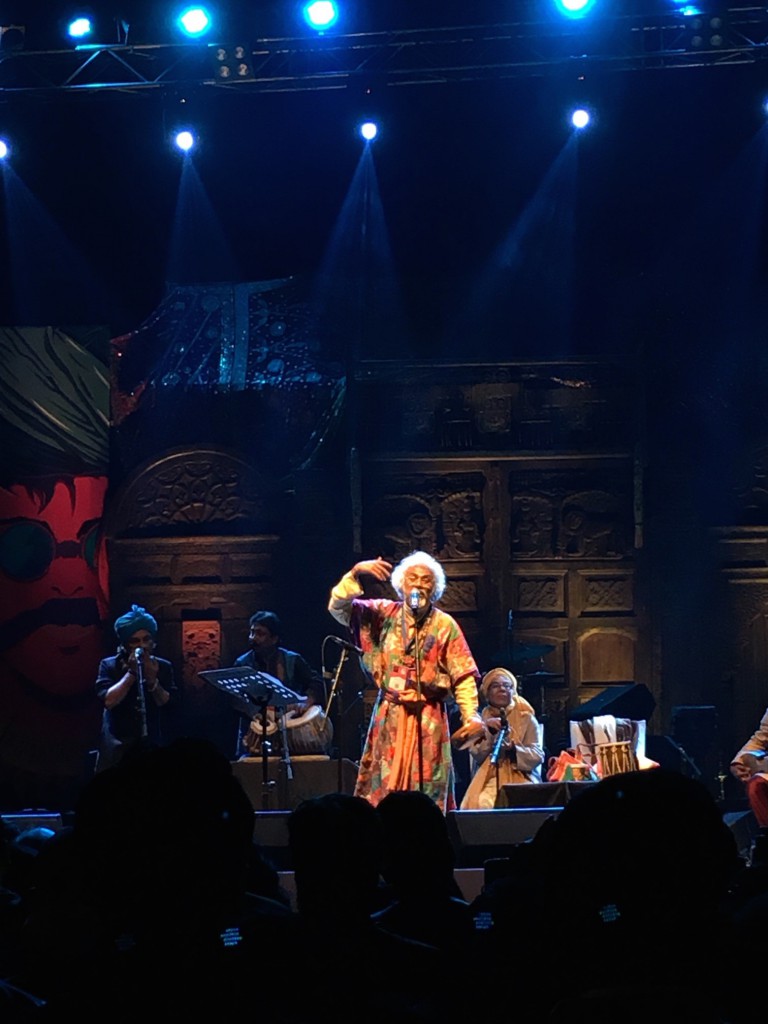

My roundup of JLF doesn’t account for either the opening and closing Writers Balls which were held at two different sprawling palaces with diaphanous tents, turbaned waiters, rousing Rajasthani music, and food and drinks for as far as you could see. Nor yet for the fancy cocktail party thrown by HarperCollins India, or the lavish dinner party at Mita Kapur’s, or the evening performance and dinner at the spectacular Amber Fort. Or any of the musical acts at Clarks Hotel every night, including my own personal life goal accomplished: seeing the legendary Bengali baul singer Paban Das Baul live in concert.

Outside the festival, I got to see leopards (prowling! eating! lounging!) at the Jhalana Forest Reserve, do a joint lecture with filmmaker Josh Steinbauer at JECRC University for their 6th annual WOW festival, and briefly wander the old city of Jaipur (hello silver earrings) one evening. As always, there’s too much to do and not enough time.

“Success isn’t like a room you get into where you transcend your life. It’s like going to a foreign county that you visit and then you come back. But you’re the same person.” – Joshua Ferris, author of The Dinner Party

Yes, JLF is crowded and overwhelming, but it is also a sumptuous treat for writers and readers alike. If you have a chance to go, take it. And if not, don’t worry because the videos of the sessions are all online. You’ll miss what it’s like to walk into Diggi Palace under a canopy of colorful puppets, or browse the stacks of Full Circle Bookstore surrounded by eager readers clutching signed books, but as Tishani says in one of her poems, “the poets, my friend, are where they have always been.”

* * *

Abeer Hoque is a Nigerian born Bangladeshi American writer and photographer. Her memoir Olive Witch (Harper 360) was released in 2017 in the U.S., and The Lovers and the Leavers (HarperCollins India) is her book of interleaved stories, poems, and photographs. See more at olivewitch.com.