The following piece is part of The Aerogram’s collaboration with the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), which documents and shares the history of South Asian Americans.

* * *

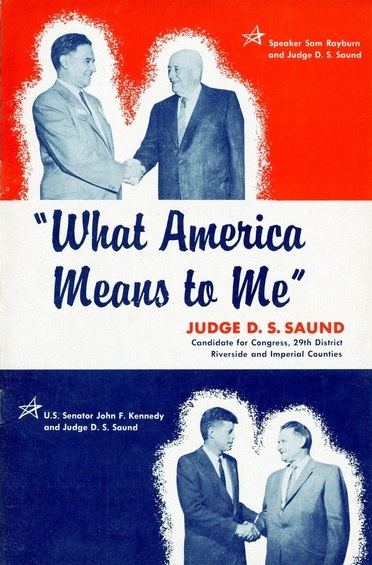

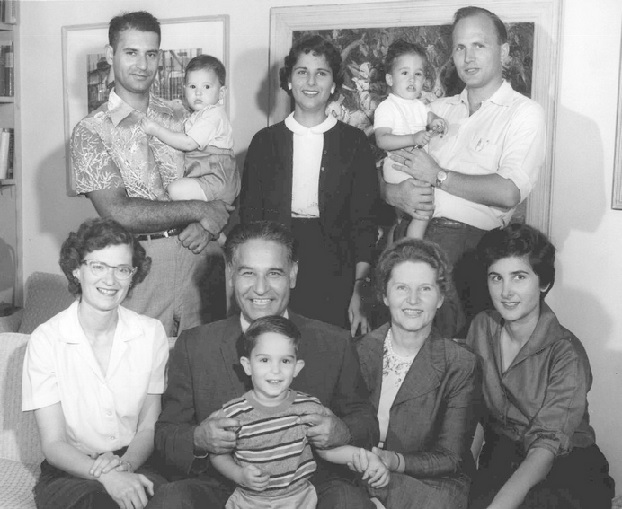

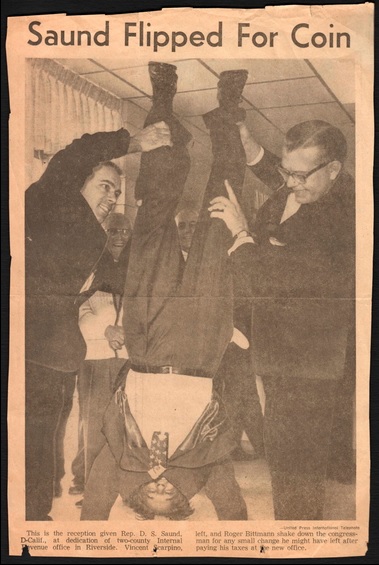

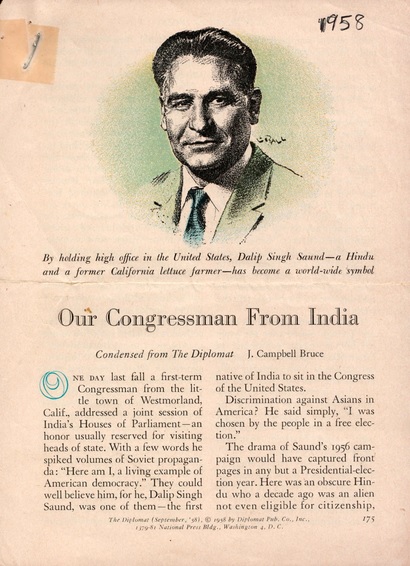

With the U.S. midterm elections approaching on Nov. 6, it’s an apt time to shine the historical spotlight on a 1950s campaign pamphlet promoting Dalip Singh Saund, the first Indian American and first Asian American elected to Congress. Representing California’s Riverside and Imperial counties, he served from 1957 to 1963 in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The pamphlet, titled “What America Means to Me” and available through the South Asian American Digital Archive, tells Saund’s personal story, in his own words. Beginning with his student days in Punjab, India, where he was born in 1899, he describes his admiration of Woodrow Wilson and Abraham Lincoln.

During World War I, he says, he read about President Wilson in Indian newspapers and “was deeply touched by the beauty of his slogans — ‘To Make The World Safe For Democracy,’ ‘War To End War,’ ‘Self-Determination For All Peoples.’” The latter slogan about self-determination must have held particular resonance for a young man in British-controlled India.

Saund wrote that reading Lincoln’s “expression of human idealism” in his Gettysburg Address “changed the entire course of my life” and inspired the young man to sail to America, where he earned a Ph.D. in mathematics in 1924 from the University of California, Berkeley.

Saund admitted that life in America had its challenges. In 1923, the Supreme Court ruled that Indians could not become U.S. citizens (because they weren’t legally white). “This worked great material and spiritual hardship on me,” he wrote. But, Saund continued, “In the good American tradition I decided not to moan or complain, but to take intelligent action.”

He became the first president of the India Association of America, which worked for a congressional bill that would make Indians eligible for citizenship. When a friend told him he was crazy for believing that Congress would ever pass such a bill, Saund told the friend, “I have faith in the American sense of justice and fair play” (italics from the pamphlet).

And sure enough, the Luce-Celler Act, allowing Indians and Filipinos to become U.S. citizens, became law in 1946. Saund became a citizen in 1949 and in 1952 was elected justice of the peace in Westmorland, Imperial County.

On the pamphlet’s back cover, Saund took his Indian heritage, which would have been a negative for a candidate, and turned it into a positive — a tool to counter communist propaganda. He wrote:

When elected I shall fly to the Middle East and to India, and appear before the people there. I shall tell them: ‘You have been listening to the insidious propaganda of the Communists that there is prejudice against your people in The United States. Look — here I am, a living example of American Democracy in practice. The American people elected me to their Congress. Where else in the world could this happen?’

Overall, the pamphlet, which effusively praises the American ideals of democracy and justice, as well as Lincoln and Wilson, comes across as positive and upbeat, and it’s clear that Saund, an outsider due to his immigrant and minority status, was trying to legitimate himself as a true lover of America. In fact, the pamphlet quotes then Senator John F. Kennedy as saying, “Saund has proved conclusively his understanding of and devotion to the basic meaning of American ideals.”

The quote, combined with a photo of Kennedy and Saund shaking hands, makes clear that Saund understood the importance of establishing a “permission structure” — in this case, getting a widely trusted white person to validate him — before the term was popularized in connection with Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. (In fact, Kennedy’s brother and daughter, Sen. Ted Kennedy and Caroline Kennedy, endorsed Obama some 50 years later right before Super Tuesday 2008.)

Saund ended up winning the 1956 election against Jacqueline Cochran Odlum, a famous and wealthy aviator who was the first woman to break the sound barrier. Newspaper headlines summed up the two unconventional candidates: “Hindu Judge Faces Rich Aviatrix in Rare Battle,” “Hindu Spices Hot Race for Congress,” “California Has Fascinating Race for Congress.” (Saund was actually Sikh, not Hindu.)

Dalip Singh Saund documentary trailer showing interview with Saund and images of newspaper headlines.

As a congressman, Saund kicked off a growing line of South Asian Americans running for national, state, and local office — a sign of one more immigrant population’s growing participation in American democracy and government. This year’s midterm elections include at least 11 South Asian American candidates running for U.S. Congress, per this list from the nonpartisan Asian Pacific American Institute for Congressional Studies (APAICS) and information from this ABC News article. The APAICS list is not necessarily complete and is not an endorsement of the candidates.

Saund said he had “faith in the American sense of justice and fair play,” and it appears that so do today’s South Asian American candidates. Regardless of background or political leaning, every American eligible to vote should do so on Nov. 6. Participating in the selection of politicians representing the people is part of being an American and creating a government that is, as Lincoln said in his Gettysburg Address, “of the people, by the people, for the people.”

More from SAADA:

* * *

Preeti Aroon (@pjaroonfp) is a Washington, D.C.–based copy editor at National Geographic and was formerly copy chief at Foreign Policy.