I recently read the book Anand Pandian wrote with his grandfather M. P. Mariappan called Ayya’s Accounts: A Ledger of Hope in Modern India.

At first I wasn’t sure if I would be able to get into this book. I don’t read a lot of anthropology these days, and I wasn’t sure that an anthropologist talking about his grandfather’s life as a merchant would in and of itself be all that interesting to readers who don’t have a special investment in Tamil culture.

It turns out my initial concern was misplaced; Ayya’s Accounts makes for pretty gripping reading, even for people who have never read this kind of first-person anthropology before. (It might help to note that virtually the entire book is written in the first person, with a strong emphasis on experiences both of Pandian himself and his grandfather. So it might be more accurate to describe Ayya’s Accounts as a dual memoir, partly written in the young, Indian-American author’s voice, and partly written in the voice of his grandfather, here translated and somewhat edited by the grandson. You don’t even have to think of the book as “anthropology.”)

It turns out my initial concern was misplaced; Ayya’s Accounts makes for pretty gripping reading, even for people who have never read this kind of first-person anthropology before. (It might help to note that virtually the entire book is written in the first person, with a strong emphasis on experiences both of Pandian himself and his grandfather. So it might be more accurate to describe Ayya’s Accounts as a dual memoir, partly written in the young, Indian-American author’s voice, and partly written in the voice of his grandfather, here translated and somewhat edited by the grandson. You don’t even have to think of the book as “anthropology.”)

I was struck by how much Anand Pandian’s grandfather’s story resonated with the stories my own grandparents have told about their lives and struggles before, during, and after Partition. To a large extent the lurid and horrific story of the Partition has dominated our accounts of the major social upheavals that occurred around the time of independence. The ways in which people who lived in Southern India were affected by events such as World War II and various migration-related displacement haven’t been studied as much, but they are equally gripping.

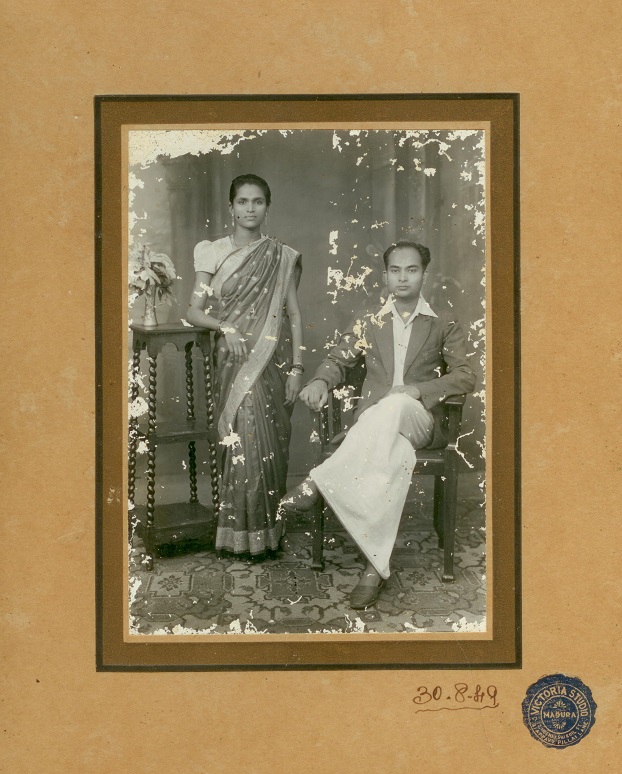

Here, Pandian and Mariappan work through the grandfather’s experience of migrating to Burma around 1930 as a child, and growing up there in the face of growing anti-Indian hostility. Around 1940, with the onset of the war, Mariappan, along with hundreds of thousands of other Indians, mainly from South India, was forced to leave the country on foot. That particular exodus bears many marks of similarity with the Partition — including criminal negligence from the British administration as well as a long and extremely treacherous component where refugees were forced to go on foot.

Mariappan walked nearly 100 miles from near Rangoon to the Indian border. It’s thought that as many as 50,000 Indians died during this process, many from cholera and dysentery. Here is a particularly striking passage in Pandian’s anthropological and historical voice:

There is an invisible nation within the nation of modern India, one that will never rally under a common flag or celebrate the memory of a common heritage. I mean [pullquote align=”right”]There is an invisible nation within the nation of modern India.[/pullquote]the multitudes of refugees scattered among the most crowded urban tenements and the loneliest corners of the countryside. Refugees from the cataclysmic tumult of the twentieth century. Refugees from floods, droughts, and other natural disasters of unnecessary gravity. Refugees from the forces of development that impoverish certain regions to fuel the prosperity of others.

The broad language here helps us see why we as readers who might not have a personal investment in the culture of a middle class merchant community in Tamil Nadu ought to be interested. The story of M.P. Mariappan resonates with that of hundreds of thousands of other “refugees from the cataclysmic tumult of the twentieth century.”

In the sense that both of my own grandfathers led their families across the divide from Pakistan to India in 1947, Anand Pandian’s account of his grandfather’s life resonates with my own grandfather’s stories of displacement and resettling — which, to my regret, I’ve only partially and inconsistently recorded. (One of my grandfathers is still alive; maybe that omission can be rectified.)

In his primary career as an anthropologist in the American academy, Pandian has been studying Tamil culture, but for the most part until this book he had not been thinking seriously about his own family’s particular history. In one of the sections told in Pandian’s own voice, the author describes a telling conversation with his grandfather that occurred during one of his visits to Tamil Nadu for fieldwork:

Suddenly, [Ayya] asked me a question that felt more like a demand, something like a sharp reminder of a promise made long ago: ‘When are you going to write my history?’

I was startled and didn’t know what to say. Ayya knew that I’d been working on a book based on my Ph.D. research. Just yesterday, nearly a hundred villagers from my research area had come by bus to attend the wedding. Was Ayya hurt that I was writing about their lives instead of his own? […]

“Ayya,” I finally managed to say, “it’s always your history that I’ve been writing. With each person’s story in that book, it’s your story that I’ve been trying to write. Only by learning the story of your life did I come to see that people’s lives have histories at all.”

This conversation, Pandian indicates, becomes the seed of the project that would lead to the writing of Ayya’s Accounts. I find this particular passage [pullquote align=”right”]Our South Asian American selves remain under the influence of our parents’ and grandparents’ stories.[/pullquote] moving because it suggests the ways in which our (by which I mean, South Asian American) selves remain under the influence of our parents’ and grandparents’ stories, even though we live in a different place geographically and often have entered into professions that are quite different from the “family business.” Pandian, as a successful anthropologist at Johns Hopkins, has still had part of his world-view shaped by his grandfather, a man with limited education who began his life as a poor fruit-seller in “some small village somewhere” in rural Tamil Nadu.

This is partly a story of caste. Mariappan’s story as a merchant both in Burma and then, after 1940, back in Tamil Nadu, is partly marked by his caste background as a Nadar. In some of his relatively rare [pullquote]This is partly a story of caste.[/pullquote] anthropological commentaries, Pandian explains the history of this caste — which began as an extremely backward group (a “tree climber” caste), but has today risen in the economic ranks, largely through the embrace of commerce.

Both in Burma and then later in Madurai, Mariappan made his way by working persistently to buy and sell goods at a profit. He claims a primary identity as a merchant — and the title of the book, Ayya’s Accounts, is clearly a nod to his grandfather’s profit-and-loss oriented thinking (“kodukkal-vaangal” in Tamil).

One of the advantages of the approach Pandian has taken in assembling the book as he has is that the sections where he speaks with his anthropologist’s voice seem to compensate for certain limitations in his grandfather’s perspective or knowledge. For various reasons, Pandian’s grandfather doesn’t dwell on how his particular caste community fits into the broader social fabric of Tamil society, nor can he fully explain the roots of the anti-Indian feeling that developed in Burma in the 1930s. Because of the dual-narrator format, Pandian can fill in those details without violating the spirit of his grandfather’s testimony.

* * *

Read an excerpt from Ayya’s Accounts on The Aerogram.

Amardeep Singh teaches literature at Lehigh University. You can find him on Twitter or on his personal blog.