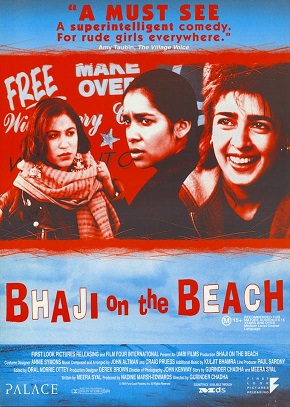

2013 marks the 20th anniversary of Meera Syal’s acclaimed film Bhaji on the Beach, directed by Gurinder Chadha. Focusing on a group of South Asian women in the U.K., the film explores the diverse relationships between first generation immigrants and their descendants. Predating such films as Bend It Like Beckham and East Is East, Bhaji On the Beach proved to be a groundbreaking film, one of few British Asian films written and directed by South Asian women with a virtually all-South Asian female cast.

A comedian, playwright, novelist, actress and journalist, Syal was born in the U.K. in Wolverhampton and studied at Manchester University. As a writer, Syal relishes the opportunity of mining characters that are conflicted and questioning what it means to be a Brit of South Asian origin — her true talent lying in her ability to capture the humor in such situations. An excellent example of such humor can be seen in the film adaptation of her semi-biographical novel Anita and Me — in a scene where Meena demonstrates a talent she is truly proud of in front of her extended family.

In an interview for The Aerogram, Syal looked back at Bhaji On the Beach and its impact on the 20th anniversary of its release and explored the direction of South Asian-focused film and television today. She also reflected on other career highlights, including her work as a novelist and with the successful BBC sketch show Goodness Gracious Me.

Bhaji on the Beach: Tackling the First Wave of Stories

It’s been 20 years since the release of Bhaji on the Beach. What are your memories of working on the screenplay?

I don’t think I realized how groundbreaking it was at the time. It’s only in retrospect that I realise it still remains one of the very few British cinema films written and directed by South Asian women with a virtually all-South Asian female cast. And it’s pretty sad that hasn’t been repeated enough since.

Getting the commission was absurdly easy, I know it would be much harder now to make the same film. Back then, I had a meeting with the new commissioner for Channel 4 film, Karin Bamborough, mentioned I wanted to write something based on the family trips we took in my childhood to Blackpool, and that was it — she said yes on the spot.

It helped that I’d just written a film called My Sister Wife which had recently aired on BBC2, but I also caught Channel 4 at the right time. Their remit then was to give voice to those sections of British society who had been largely ignored by the mainstream channels, and I guess I fitted the bill! Writing it was the usual tortuous process of endless rewrites which is the norm, and I missed seeing any of the filming as I gave birth to my daughter on the first day of the shoot.

But I remain hugely proud of the film and everyone who worked on it. It has a certain naïve roughness as you’d expect, when you’re given the space to tell stories you’ve wanted to tell for so long, you want to put everything in it, in case you never get the chance again, (and how prophetic that was…). So we covered subjects such as domestic violence, divorce, interracial relationships, repressed housewives, rebellious teens — we wanted a whole span of the female Brit South Asian experience.

But I like to think the heart and the energy of the film overcomes the broad canvas we gave ourselves, and it’s great that it is still remembered fondly some 20 years later.

What did you hope to achieve with the film?

I think what it hopefully achieved, which was to give air and space to the lives of a group of women who were considered invisible to most of British society. And also to be honest about some of the issues they/we were facing, to kick-start the debate but do it through humour and vivid story telling. Inevitably there were some people, mainly older conservative men, who didn’t like the film and even in some cities, picketed the cinemas demanding their women and girls shouldn’t watch the film for fear of being “corrupted.” (Which just proved how they had no idea of what their women and girls really thought or were up to behind their backs.)

[pullquote align=”right”]No film can solve an issue, all you can do is hope to open the conversation.[/pullquote]What was really satisfying was seeing all those women, mothers with daughters, going in to see the movie anyway, and I hope it led to some very honest conversations afterwards. No film can solve an issue, all you can do is hope to open the conversation. From what I was seeing around me, many young South Asian women were leading double lives, torn between their own need to experiment/explore versus huge family expectations. For others it was the pain and silence of putting up with unhappy or violent marriages, all the dirty linen we were told should never be washed in public, the old rule for women of put up and shut up. What we hoped was that the film would show not only was this stuff going on, but that it was important to admit it, only then can you begin to address the problems.

It seems rather quaint now that anyone would be shocked by a film that depicted domestic violence in our community, and I hope this shows how far we have come in some respects, and conversely how much there is still to explore, debate and heal. Although there had been films and TV shows by male Brit-Asian writers, such as Hanif Kureishi’s My Beautiful Launderette and Farrukh Dhondy’s series Tandoori Nights for Channel 4, there was a real lack of female voices.

Did you have that in mind when working on the film?

Did you have that in mind when working on the film?

I think the fact that the creative team were so overwhelmingly female was a statement in itself, and of course we wanted to add female voices to the mix. If you want to know what a woman really thinks, ask the woman, no?

We didn’t just want to play the supporting roles of daughter/wife/mother to the men, and it’s gratifying now to see the handful of breakthrough women changing that with their work; the established such as Mira Nair, the newbies such as Lily Singh and natch Mindy [Kaling]. The change never seems fast enough whilst you’re waiting for it, it’s only when you look backwards you go, okay, things are moving. I’m just impatient. I want to be able to work with all these amazing women before I get too old to get out of bed and answer the phone call.

Before Bhaji on the Beach, we’d never seen the theme of the traditional and the modern going head-to-head, explored in relation to Brit-Asian women.

Do you think that is still an area that isn’t being explored enough in the arts?

[pullquote align=”right”]We have tackled the first wave of stories, now it’s time to go larger and deeper with them.[/pullquote]I think there are so many more stories to tell about our women and it’s so much more complex than just the generation gap issues we faced as first-generation women. It’s not so much Arranged Marriage Versus Love Marriage arguments any more, but more complicated and subtle areas like how do you make a relationship/marriage work when you’re holding two sets of expectations in your head? What you inherit and what you aspire to? How do we negotiate the minefield of sexual expectations instilled by years of cultural conditioning? How do you bring your kids up, admiring Nanima/Dadaji or determined not to repeat their apparent mistakes? How do you tell your parents you’re gay when it’s still illegal in most of our countries of origin? I find it interesting as a mother myself how I approach bringing up my own son and daughter when compared to my own upbringing. We have tackled the first wave of stories, now it’s time to go larger and deeper with them.

Goodness Gracious Me: Finding Each Other & Coming Home

I’d kick myself if I didn’t ask you about Goodness Gracious Me. Did you and the rest of the cast ever imagine the show becoming such a hit across the globe?

I think it took us all by surprise, especially as it took so long to get the show on tv. First we had to do a live try-out, in the theatre, then we were given a brief radio series, then a tv pilot, and at every stage we could have been cancelled. But what kept it alive was the fact that we had nothing to lose, we weren’t known, we had all this material many of us had been doing as solo performers as well as the new stuff we created together and our only brief was, do we find it funny?

We didn’t write to any audience demographic because no one thought there was an audience for what we were doing, and that was pretty liberating. It meant we were able to pool all the crazy stuff that had been making us laugh growing up as second generation Indian kids in Britain. Finding each other, finally meeting a whole bunch of people who shared the same weird shorthand as you was like a coming home of sorts. That’s what made the show so infectious, people could tell we were being utterly ourselves and having a ball at the same time.

What was the creative process behind all those memorable sketches?

Some of the material would come out of us sitting around and gossiping about our childhoods, families, relatives. It was like the best kind of group therapy. But we were also ruthless about what went in or out, so much stuff didn’t make it to the shows. Then the more disciplined of us would actually go away and write stuff down, or sometimes one of us would arrive with a fully formed sketch, and then it would have to get through the rest of the creative team. But a lot of the material came from memory and observation. I especially enjoyed writing a lot of the comedy songs. I’ve always enjoyed a good musical pastiche, and it was another avenue of being playfully satiric.

Is there a character you’re particularly fond of from the show?

I’ve always had a soft spot for Smita Smitten, showbiz kitten, who was inspired by a gossip column I remember reading in a Hindi film magazine years ago called “Neetu’s Natter” and was always, for some reason, accompanied by a drawing of a black cat with a smoking cigarette holder in its mouth. (Hence Smita’s catchphrase, “Miaow Pussycats.”)

I like to think she’s now in semi-retirement somewhere in the Malabar Hills, soaked in gin and still managing to miss her mouth when applying lipstick.

What do you think Goodness Gracious Me did for British comedy and South Asian diaspora comedy across the world?

I hope that it proved at least that we have comedy bones, something people really didn’t think about us way back then. We were seen as the shopkeepers/doctors/newsagents/restaurauteurs, hard-working, passive, insular. [pullquote align=”right”]If you make someone laugh, you’re not The Other any more. [/pullquote]That’s the amazing thing about comedy, it breaks down preconceptions in a way that a thousand political speeches can never do. Being funny is a powerful place to be, especially when you’re not the punchline of other people’s crass racist jokes but are actually pulling the comedy trigger yourselves.

If you make someone laugh, you’re not The Other any more, you’ve dragged them into your world view and made them laugh. And also the ability to laugh at yourselves and others is a supreme sign of confidence.

2 thoughts on “20 Years After ‘Bhaji on the Beach’: Meera Syal on South Asians in Film & TV”

Comments are closed.