The following piece is part of The Aerogram’s collaboration with the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), which documents and shares the history of South Asian Americans. This month’s piece ties to Women’s History Month.

***

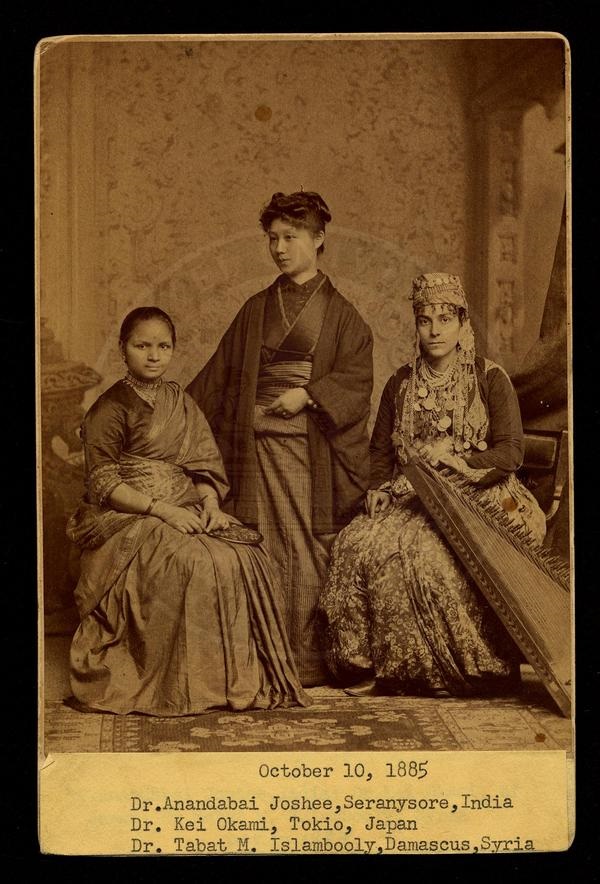

“The voice of humanity is with me and I must not fail. My soul is moved to help the many who cannot help themselves.” These words were written in 1883 by Anandibai Joshee in a letter pleading to be admitted to the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania.

Born in India in 1865 and married as a child in 1874, Joshee would go on to become the first South Asian woman to go abroad and earn a degree in Western medicine when she graduated in 1886 from the Philadelphia-based medical school, now part of Drexel University College of Medicine. (That same year, Kadambini Ganguly became the first South Asian woman to earn the same degree within India when she graduated from Calcutta Medical College.)

The challenges and barriers Joshee had to overcome were extraordinary. Not only was Joshee married before she had even reached age 10, but she lost a baby at age 14. That tragic loss, as well as the grossly unmet health care needs of so many other Indian women, moved her to pursue a medical degree.

In her letter begging for admission into the medical college, she said she faced “the combined opposition of my friends & caste” but that her determination would enable her to succeed in her purpose: “to render to my poor suffering country women the true medical aid they so sadly stand in need of.”

Life in the United States was difficult for Joshee, who arrived all alone when she was just 18. She was in poor health and wasn’t used to the food or weather. With her health declining, the dean of the medical college let Joshee move in with her so that the sickly student could prepare foods that were more familiar and in line with her religion.

Joshee persevered and graduated in 1886, a time when women in the United States hadn’t been permitted to study medicine for all that long. When she graduated, Queen Victoria sent a congratulatory letter conveying her appreciation upon the occasion of “the first Hindu woman to receive a medical degree in any country.”

Joshee received a job offer to head the female ward at Albert Edward Hospital in Kolhapur, in Maharashtra, India. She sailed back to India but continued suffering from poor health, ailing from tuberculosis, and shortly after returning, she died in February 1887 at age 21. She was never able to actually practice medicine. The dean of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania wrote, “She sealed with her early death the superhuman effort to elevate her countrywomen and to minister in her own person to their physical needs.”

It’s important to recognize the allies who opened doors of opportunity for Joshee at a time when women had severely subordinate status in India and when people of color faced enormous discrimination in the United States. First, Joshee’s husband, who worked in the postal service, was ahead of his time and encouraged Joshee to pursue her medical studies in the United States. He even traveled to Philadelphia for her graduation ceremony.

American Theodocia Carpenter read a request for help from Joshee and her husband that was published in the Missionary Review. Moved by the appeal, Carpenter responded and acted as Joshee’s “aunt” when the teenager arrived alone in the United States. And there was Dean Rachel Bodley, who let Joshee move in with her after Joshee’s health started declining shortly after enrolling as a student.

As we reflect on pioneering women during Women’s History Month this March, it’s worth mentioning that Joshee was one of the earliest in a long line of brave South Asian women who have come to the United States alone on their own — a formidable achievement in a patriarchal culture. As noted in the book Indian Immigrant Women and Work: The American Experience, coming to America was, for many of these women, a small act of rebellion against prevailing cultural norms. Even today, South Asian “good girls” are often supposed to marry doctors, not necessarily become doctors. It’s encouraging to know that South Asian women who push back against patriarchal culture and break repressive cultural norms have generations of women like Joshee behind them.

***

To help share Anandibai Joshee’s story and support the South Asian American Digital Archive, you can visit shop.saada.org to buy a Pardon My Hindi-designed T-shirt with her photo on it. You can use the code “AEROGRAM” to get a 20 percent discount on your order.

***

Preeti Aroon (@pjaroonfp) is a Washington, D.C.-based copy editor at National Geographic and was formerly copy chief at Foreign Policy.