The tropical morning mist had begun to lift. I stepped through the ornate, bejeweled lobby, spun through the revolving doors and hurtled out onto the sidewalk. My wife stepped out beside me.

“There’s the bus. Where are your brother and his wife?” I asked.

“The twins aren’t feeling well, so they have to show my parents where the medicine and diapers are stashed.”

We were in the Dominican Republic for a family vacation at one of those all you can eat and drink monstrosities and this morning we had booked an all terrain vehicle excursion. It was something I swore I would never do. They put you in what amounts to a large go-cart with monstrous wheels, pump it full of diesel and you roar through the Dominican countryside like an angry colonialist with irritable bowel syndrome. But, truth be told, shit did seem kind of fun. And why should imperialists be the only ones having a good time?

We showed our receipts to the tour guide and stepped onto the packed bus, taking a seat next to the only other couple of color. A friendly black man, his Indian wife and their two adorable daughters slid over to make room. We smiled and exchanged hellos.

The tour guide turned to the group.

“We waiting for two more peoples.”

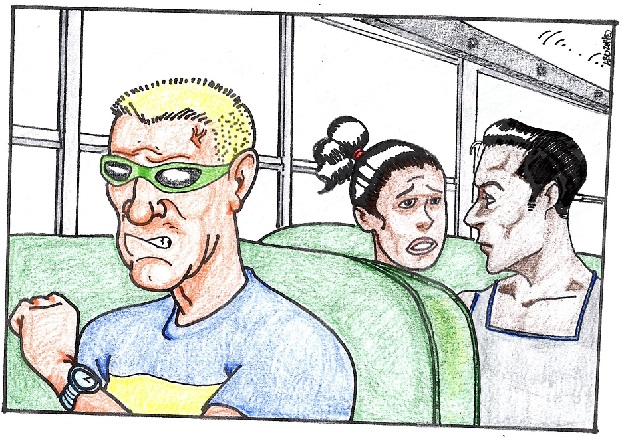

A large group of ten pasty faced Maine tourists looked around incredulously. A young girl, sitting confidently on the insufferable precipice of 16 years of age, scoffed.

“Are you kidding me?” she squealed.

A man in his early 40s with wrap around sunglasses and an angry buzz cut shook his head.

“You said we would be out by 7:30. I want a refund,” he croaked. “And what’s up with the AC?”

“Relax,” said the tour guide. “Here, you on Dominican time. The carts aren’t going nowhere. We enjoy.”

The girl, egged on by a mother who looked like a candidate for Real Housewives of Staten Island, continued her ranting.

“Let’s go. We don’t like them anyways! Let’s go!”

My wife and I looked at one another. I was surprised that no parental figure had told her to “shush.” Aside from getting ripped off by locals, white people enjoy a tremendous amount of privilege when they travel to brown and black countries. This girl was the punkish embodiment of this entitlement.

I closed my eyes and tried to imagine being a young boy, raised in India instead of Pittsburgh. I imagined my accent heavy, my skin darkened by the summer sun, coming to visit America and yelling in front of a crowd of white people, demanding my selfish emotions to be heard and felt. My parents enabling me by laughing. It was unimaginable.

Simmering, I took a deep breath and spoke.

“Hey everyone. Sorry, we’re waiting for my brother-in-law and his wife. Their young twins are really sick so they’re taking care of a couple things and will join us very shortly.”

There were a few “awww’s.” A handsome, smug-looking man with Aviators and a George Clooney chin turned around.

“What, they leave ’em out in the sun too long?”

Some of his friends chuckled.

“Yea, because my nephews are little black raisins.”

The laughter stopped. The angry crew cut turned to glare at me.

“Easy there, sand nigger. Watch who you’re talking to,” I imagined him saying.

And there was my brother-in-law exiting the lobby. Zipping up a bag, half-jogging. His wife came hustling behind him. One toddler is a job, two is a career.

They jumped up onto the bus. Smug man turned around.

“You leave the kids by themselves?”

My brother-in-law chuckled nervously as we rumbled towards our excursion.

I thought to myself, this is the fiery white privilege that has poked at me my entire life. Each searing ember, a reminder of the taunts of my youth. Jabs about Gandhi, curry smells and Hindoos. Childhood pain and alienation needs only a casual adult encounter to resurface.

Adulthood, however, also gives us the benefit of coping mechanisms. As we got to our ATV’s, I shook away the thoughts, got in the driver’s seat, and roared.

* * *

The next morning, we awoke at 6:30 a.m. for my wife’s birthday. I had spent the night alternating between shivering and sweating profusely, with projectiles of varying consistencies ejecting from my orifices. Maybe the six lobster tails I had eaten the night before weren’t such a good idea.

“Get up. It’s not your day, stupid,” I told myself as I flopped out of bed.

We were going on a catamaran ride with my wife’s folks. After meeting them at breakfast for a quick bite, we boarded the tour bus.

My father-in-law, a pediatrician, bemusedly asked, “How are you feeling?”

Having doctors in the family is great for emergencies, but when it comes to the daily stuff, they’ve seen it all, done it all. Your vomit and runs don’t concern them.

“I’m good, Dad. Much better now.”

I sat down and gently vomited into my mouth. Swallowed. Turned to my wife.

“Happy Birthday, babe!”

* * *

The bus stopped at a few hotels along the way, picking up more passengers for the boat trip. We stopped after thirty minutes and transferred to a different bus. I saw another Indian family.

I nudged my wife. “Hindus,” I whispered.

Perhaps this is the case with other minorities, but when Indians see other Indians in unexpected places (i.e. the Dominican Republic, a farm, a hockey game) we usually avoid eye contact, then try to sneak a peak when the other isn’t looking. Their presence is a reminder of how impossible it is to be brown and not catch attention in non-brown settings. Sometimes this creates camaraderie, but usually it’s resentment.

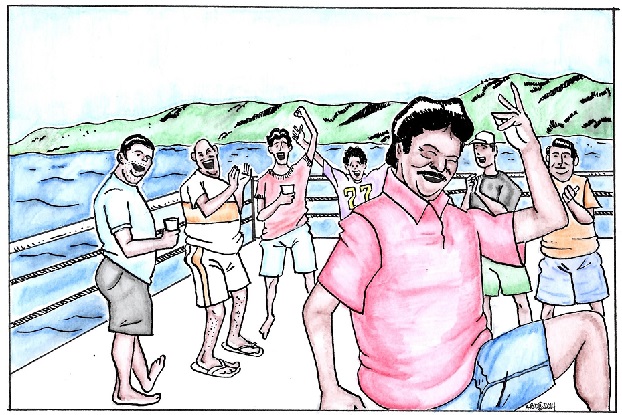

Another Indian family emerged from behind the bus. And then another. A maple colored man with a large bushy moustache and a baggy Ferrari shirt cloaking an enormous paunch bellowed in an Indian accent, “23! Group 23!”

I felt like I was supposed to go up and get my dosa.

More Indians emerged from behind the bus in cartoon-like fashion. There were mothers, fathers and nearly a dozen kids in differing stages of gangly pre- and post-pubescence.

One little, two little, twenty-three little (actually kinda big) Indians!

When we finally reached our destination, we all got out, walked through some woods, past groups of peddlers selling cheap cigars, rum and 5-dollar ice cream bars, and emerged onto a beach. The tour guide split us into small groups and took our pictures. A trio of kids played drums and danced, while a tattered purple Yankees cap collected American and European currencies.

I was still queasy from the morning and Group 23’s increasing volume wasn’t helping. They had already photo bombed our family picture, and the kids were tickling each other and being generally noisy. Still, this group was an anomaly here, and they intrigued me. My wife was not as amused, mostly because they were from the same part of India as her family.

“That’s your people,” I condescended.

We boarded a speedboat that took us to a catamaran — a white, vulgar chunk of maritime furniture. But the water was beautiful. Bright blues and deep emerald hues sloshed against the side of the boat. A crisp, gentle sea breeze whispered across my face. I took a deep breath and exhaled. Finally. We made it. I looked at my wife and smiled.

“SANTOSSSSSSSHHHH!”

I turned to see the portly fellow in the Ferrari shirt yelling to his friend across the deck. He held up a half glass of rum and gulped it down. Reggaeton music began blaring from the speakers. The captain, a man in his early 30s with his entire head shaved, save for a thick, inexplicable swath of hair above his neck, nodded his head to the music. He revved the motor, cranked the music and we began our journey to the island.

After a couple of drinks, the annoyance melted away and life started to make more sense. “This is what it’s all about,” I said to my wife.

The captain spoke into the microphone. “OK everrrybody, time you do one shot and REPORT TO THE DANCE FLOOOORR!”

Group 23 screamed and flooded the middle of the boat. Two instructors stepped in front of the impromptu dance floor.

They started dancing and everybody followed. The Indian uncles were high-fiving in between large gulps of rum, picking each other up and yelling to everyone and no one in particular. My in-laws were embarrassed and I was less amused than before. Still, we joined in on the dancing. Group dances look insufferable from the outside, but when you’re in the middle of them, they ain’t so bad.

The situation was getting drunker and louder. So when we finally arrived at the island, we quickly ate at the buffet and found an isolated spot to swim and lounge for the next couple of hours. I had almost forgotten about Group 23, until it was time to head back onto the boat.

They had continued drinking, and things had gone from amusing to sad.

As we pulled into a protected reef to see starfish, one of the drunken men tried to jump off of the boat and into the shallow reef below. Luckily, a guide stopped him from hurting himself. Another fellow rode piggyback on another man as he splashed loudly amongst the children. Yet another man with a shit-eating grin plastered to his face balanced a starfish on his head while wading around with a bottle of rum.

“Parrrrrrrrty!” he yelled into the empty horizon.

* * *

The sun was setting when we eventually found our way back on the bus. One by one, Group 23 and others made their way off of the bus to their respective destinations. As the alcohol-fueled ebullience wore off, some nodded their goodbye to my in-laws, some bashfully avoided eye contact.

Driving through the lush countryside towards our hotel, I felt that third world-vacation feeling sink in: a mixture of relaxation and shame. Sun, sand and the ocean are inarguably therapeutic, but the pathways we must negotiate to get to these places are complex. I often wonder if it’s worth it.

And with an ever-expanding global economy comes an increased access to wealth and privilege for non-white people. So can we act just as entitled and privileged in places that aren’t our home? Sure.

The real question is, should we?

* * *

A.T. Kapoor is a writer who lives in New Jersey.

Illustrator Aaron Overton is an attorney who lives in New Jersey with his long-term partner and cat.