Oh Darling, Kiss is India! Parodevi Pictures http://t.co/hAnid2dlNg

— Kafila (@kafila) November 4, 2014

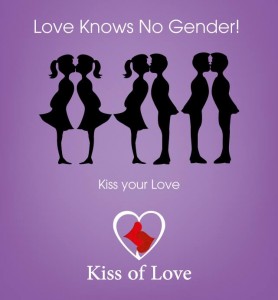

On November 2, thousands of young women and men took to the streets of Kochi in Kerala and locked lips to protest moral policing by right-wing forces in the state. The campaign started after the youth wing of the conservative Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) vandalized a coffee-shop in Kochi, accusing its owners of promoting immorality. Borrowing tactics, whether consciously or not, from the LGBTQ movement, young people took to the streets to “flaunt” their love in the face of repression. Some locked lips with their partners, while others planted shy pecks on the cheek of friends and loved ones. All expressions of love, platonic or otherwise, homosexual or heterosexual, were welcome and celebrated. In the days leading up to the rally, right-wing protesters ripped up “Kiss of Love” campaign posters and took to social media to threaten violence against anyone who participated. But these intimidation tactics did not deter the young activists. Youth from other Indian cities, including Kolkata and Delhi, planned marches in solidarity.

In a country plagued with various forms of everyday violence, why did this particular instance of vigilante violence against a coffee shop spur such a revolt? Why did this particular form of protest capture the imagination of the youth? How do they speak to transnational protests around sexual autonomy and expression?

In many ways, the “Kiss of Love” rallies share much in common with the SlutWalks that began in 2011 in Toronto and spread to cities all over the world, including several cities in India. SlutWalks challenged a culture that excuses sexual assault or harassment by pointing to a woman’s appearance or actions — in short, blaming the victim. Marching in revealing clothes, playing loud music and dancing “provocatively,” SlutWalkers took to the street to assert their bodily autonomy and individual freedom. The Kiss of Love marches had a similarly festive atmosphere as the exuberant youths filled the streets with painted faces and colorful costumes. They played drums, sang and danced in their march for the individual’s right to self-expression without fear or shame. In spite of these similarities, there are a few notable differences between the two sets of protest movements.

First of all, the Kiss of Love march is a locally grown campaign that responds to a regional issue rather than replicating one germinated in the West. Of course, this fact did not stop right-wing religious activists from arguing that the idea of the kiss itself is a western conspiracy. To which, Kiss of Love activists promptly responded by circulating a map of India with the words for kiss in various Indian languages.

Secondly, in contrast to the SlutWalks, the Kiss of Love campaign addresses multiple systems of violence that share a common root: bigotry. The SlutWalks sought to fight victim-blaming by reclaiming the word “slut,” a word that is used to regulate the white and upper class women’s sexuality, but did not necessarily speak to larger systems of violence. Slut is a word often pegged on a woman in order to dismiss her claims that she has been sexually assaulted or harassed. By that logic, women are advised: if you want to avoid being raped, don’t dress/act like a slut. The SlutWalk participants sought to turn this logic of sexual discipline on its head by dressing and calling themselves “sluts.” However, as some feminists of color have pointed out, not every woman has the privilege or the space to call herself a “slut.” The term SlutWalk does not address the systems of violence against women of color who are already and always considered public — therefore, they have no “honor” to lose. This is as true for Black women in the United States, as it is for lower class/caste/Dalit women in India.

Rather than simply an assertion of personal freedom, the Kiss of Love campaign addresses multiple systems of oppression that exist in the country. At its heart, moral policing is about regulating women’s sexuality. In a society where the rape of a woman is often seen as a crime against her family and her community, women kissing in public are reclaiming their agency. This act of kissing challenges narratives about “women’s honor” that perpetuate the objectification of women’s bodies and devaluation of their lives.

India’s “Love Jihad” An Attack on Muslims but also Women & Love http://t.co/bnPLfcwzcl by @soniafaleiro @nytimes oped pic.twitter.com/JScNBnf7lB — Raju Narisetti (@raju) November 1, 2014

Moreover, by engaging in public expressions of affection that trespass boundaries of caste, religion and sexuality, young people seek to demolish rigid social norms and hierarchies. To understand the gravity of such acts, keep in mind that both men and women are still being brutally killed by their own kin for loving or marrying across Caste and religious lines. And indeed, Hindu right-wing forces are engaged in a fear mongering campaign that warns Hindus that their daughters are at risk of being lured into marrying Muslim men in an organized conspiracy, aka Love Jihad. The fear of the Love Jihad operates on the dual logic of othering Muslim men and denying women’s agency.

And of course, same-sex kissing at the march challenges the recent Supreme Court decision to reinstate Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code that once again makes homosexuality a crime.

Thirdly, the Kiss of Love campaign is unique in the way it engages with hegemonic Indian masculinity. By publicly expressing their love, young men are modeling an alternative form of masculinity that does not require them to repress their emotions. In contrast, while there is evidence that some men also participated in the SlutWalks by wearing short skirts and tee-shirts labeled “sluts,” not all men have the privilege of wearing skirts in protests, particularly gender non-conforming men.

Finally, the Kiss of Love protests achieve something all the SlutWalks and marches to end rape cannot; this campaign manages to celebrate women’s sexual autonomy without having to recall or refer to women’s unending suffering in the hands of men. In this march, the world is forced to confront women on our own terms — as lovers, not victims.

Diya Bose is a Bengali-American writer and a sociologist-in-training based in Los Angeles. Find her on Twitter at @DiyaCBose.