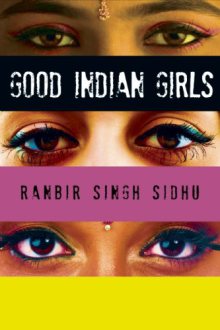

Playwright and novelist Ranbir Singh Sidhu has a new collection of 12 stories called Good Indian Girls. Sidhu was born in London and studied archaeology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a winner of the Pushcart Prize in fiction and a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship. In Good Indian Girls, Sidhu aims to provoke, taking on issues of identity in the South Asian diaspora, featuring characters who are often deeply conflicted and in situations that are neither comforting nor cliché. In an interview conducted via email with The Aerogram, Sidhu kindly shared his thoughts on the short story format, his literary heroes, facing “good Indian boy” expectations, and how his years in California have influenced him, among other topics. He has also shared an excerpt from his new collection.

Playwright and novelist Ranbir Singh Sidhu has a new collection of 12 stories called Good Indian Girls. Sidhu was born in London and studied archaeology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a winner of the Pushcart Prize in fiction and a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship. In Good Indian Girls, Sidhu aims to provoke, taking on issues of identity in the South Asian diaspora, featuring characters who are often deeply conflicted and in situations that are neither comforting nor cliché. In an interview conducted via email with The Aerogram, Sidhu kindly shared his thoughts on the short story format, his literary heroes, facing “good Indian boy” expectations, and how his years in California have influenced him, among other topics. He has also shared an excerpt from his new collection.

Who should read Good Indian Girls?

Everyone, except maybe a few of my aunties! But more seriously, I don’t know who should read the book, but I do hope that whoever does, finishes it having felt challenged and moved and pushed outside of their comfort zone. I suppose if there’s someone out there who has a narrow expectation of what it means to be South Asian today, or to be of South Asian descent, then that’s someone who should certainly read the book.

[pullquote align=”right”]In my view, one of the central purposes of art is to unsettle.[/pullquote]In my view, one of the central purposes of art is to unsettle, and to destabilize our own fixed notions of who we are, and who our fellow humans are. If, after having read this collection, the ground is a little more unsteady under the reader’s feet, then I’ve done my job. There’s something of the natural provocateur in me, and I get bored when everyone is going along nicely and not questioning the larger structures of their own lives. So I do hope that it provokes, and that it reaches those people who are at the moment sitting a little too comfortably in their own lives.

Some of your stories, like “Border Song” and “The Good Poet of Africa” are set in California. What influence, if any, do you think that living in California earlier has had on your life and writing?

[pullquote align=”right”]After growing up in the UK, California felt like a liberation.[/pullquote]I moved to California when I was 14, and finally left when I was around 30, so I lived many of my most formative years there. I can’t say what influence it had in my writing, except that as a place living inside my imagination, it continues to haunt and engage me. After growing up in the UK, California felt like a liberation, and was so different it was hard at first to figure it out, or to feel at home there. It was only when I returned for an extended trip alone to the UK when I was in my late teens, that I began to understand how American I had become, and how American I felt. Growing up there has had a large influence on how I view America, and though I live in New York these days, I often feel more at home in the American West.

How did you decide which stories to include in your collection?

It wasn’t about choosing stories, but about realizing at some point that I had enough good stories which I felt were strong enough to stand shoulder to shoulder inside a book. I wasn’t sure at first whether they would hang together, whether something close to a coherent vision would emerge, but I think now that it does, and that the book, as a whole, works strongly on many different levels. These stories feel like they belong together, and I doubt I’ll write stories quite like these ever again.

If you had to pick a favorite story from the collection, which one would it be and why?

I can’t — the stories for me are so different, and written over so many years, that to choose one would be futile. I was surprised recently by one story. This is “Bodies Motion Sound,” which is about a young woman who discovers she is pregnant and, on the spur of the moment, runs away from home. It’s also about the hangover from Idi Amin’s expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1971. I was editing it for the US release, and had forgotten what a really fine story it is. It’s one of the three stories in the collection that had remained unpublished, and I can’t figure out why, except that it doesn’t conform to the expectations many editors here in the US have of what a story about Indian Americans should be.

The story “Good Indian Girls” in the collection offers some disturbing perspectives on the kind of expectations and ideas people might have about what it means to be a “good Indian girl.” Have you ever faced expectations that you would or should be a “good Indian boy”? If so, what was that like for you?

I think in many ways that I still do face those expectations. I certainly grew up with a very restricted sense of who I was, and who I could be, because of the world I lived in — family, and the broader, often emotionally shriveled, world of London in the 1970s.

[pullquote align=”right”]The weight of cultural heritage and expectation fell much more on girls.[/pullquote]But I always felt, even when I was quite young, that the expectations placed on girls, and later women, were much more onerous and heavy than the ones placed on boys. Especially among Indians living abroad, the weight of cultural heritage and expectation fell much more on girls, they were the ones who were supposed to carry forward India into the new worlds people were living in. As a young man, I had a relative sense of freedom from much of that weight, and could escape it more easily, though it was an escape that carried with it its own costs. If I had been a young woman, I don’t doubt I would have a much harder time of it, and any break from it would have been much more ferocious.

very insightful!