In Desis Divided: The Political Lives of South Asian Americans (UMN Press), Sangay K. Mishra writes about the changing nature of the politics of immigrant inclusion — and difference — in America. From Europeans in the early twentieth century through later Latinos, Asians, and Caribbeans, gaining social and political ground has generally been considered an exercise in ethnic and racial solidarity for immigrants in America. The experience of South Asian Americans, one of the fastest-growing immigrant populations in recent years, tells a different story of inclusion — one in which distinctions within a group play a significant role.

Mishra focuses on Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi American communities and analyzes features such as class, religion, nation of origin, language, caste, gender, and sexuality in mobilization to explore how these lead to multiple paths of political inclusion, defying a unified group experience.

Sangay K. Mishra’s book is the first of its kind involving the politics of South Asians in the United States. Desis Divided fills an important gap in the study of Asian American politics and speaks to a larger literature on minority political incorporation, showing both the strengths and limitations of Desi political involvement. —Karthick Ramakrishnan, University of California, Riverside

Read the excerpt below from the book’s introduction: “Situating Desis in U.S. Ethnoracial Politics,” and then head over to read Shyam Sriram’s review of Desis Divided.

The Tide of Turbans and Racial Exclusion

The early history of South Asians in the United States was characterized by racialized exclusion and community activism to contest racism and denial of equality, as well as the building of transnational alliances to overthrow British colonial rule in India. Historical records show that more than six thousand Indian immigrants, primarily peasants from British India’s Punjab province and a small group of students, came to the western United States between 1899 and 1913 (Jensen 1988, 170–7 1; Takaki 1998, 294).

A large majority of these early migrants were Sikh peasants from the Doab region of Punjab along with Muslims and Hindus from other parts of India. A significant number of them were veterans of British colonial military forces who had traveled around the world and had no intention of going back to their small landholding economies, which were reeling under the changes introduced by British colonial policies that placed small landholders in an extremely vulnerable situation (Ramnath 2011, 17–18).

The early Punjabi migrants to the United States found work primarily in lumber mills, railroads, and construction in California and Washington state. However, their encounter with the racial structure of U.S. society was immediate and swift. Feared as cheap competitors, South Asians were driven out of employment in the railroad and lumber industries by white workers. In September 1907, for instance, the Indian community in Bellingham, Washington, was brutally attacked by white workers, and several hundred of them were forced to cross over to Canada for their protection. A similar attack on Indian workers took place two months later in Everett, Washington, where they were forcibly rounded up and expelled from the town (Takaki 1998, 297–303).

“Ethnic Punjabis numerically dominated the migration from India to the United States during the British colonial period.”

The Asiatic Exclusion League took up the task of fighting the “Hindoo Menace” and asserted: “From every part of the coast, complaints are made of the undesirability of the Hindoos, their lack of cleanliness, disregard of sanitary laws, petty pilfering, especially of chickens, and insolence to women” (The Hindoo Question in California 1908, 8–10). Driven out of lumber mills and railroad construction by white workers, Punjabi migrants took to agricultural work that was already dominated by Asian labor from Japan and China. However, agriculture was in constant need of new labor since the Chinese Exclusion Act stopped the inflow of Chinese labor and the Gentlemen’s Agreement with Japan cut the inflow of Japanese labor. Despite facing persistent anti-Asian mobilization, Punjabis did find work in agriculture, and many of them even managed to buy agricultural land and become owners (Takaki 1998; Jensen 1988; Leonard 1992).

The roots of Pakistani and Bangladeshi American communities were also planted in this period. As pointed out earlier, ethnic Punjabis numerically dominated the migration from India to the United States during the British colonial period. Many ethnic Punjabis came from West Punjab, which became a part of Pakistan, created in 1947 after the end of British rule. A great majority of these Punjabis were Sikhs, but a small number of them were Muslims as well. One of the earliest Muslim communities with distinct Pakistani roots was established in Willows, in northern California. Fazal Mohamed Khan, a Punjabi immigrant who came to the United States in the 1920s and became a successful farmer and entrepreneur, helped establish a mosque in the area and was instrumental in nurturing a thriving Muslim community that later identified itself as Pakistani (Bagai 1967).

However, the period from 1947 to 1965 saw only a small trickle of Pakistani immigrants since there was a numerical restriction on immigrants from most Asian and Latin American countries. According to one estimate, 1,800 Pakistanis were granted immigration status in this period. A large number of the newcomers in this period were family members and relatives of those who were already in the United States. During the 1950s and afterward, there was an increase in the number of nonimmigrant visitors from Pakistan who came as a result of deepening military and political ties between the two countries. A sizable number of these visitors, who came for education or training, went on to stay and acquire immigrant visas over time (Najam 2006, 49–50).

“Another stream of migration in the early twentieth century was South Asian seamen — primarily Bengali Muslims — who jumped British ships docked at the harbors of U.S. cities.”

Bangladesh, a nation that came into existence in 1971 aft er a bloody separation from Pakistan, also has a long history of migration that is deeply linked to the larger history of South Asian migration to the United States. The Muslim peddlers and seamen who came to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries belonged to the part of South Asia that was known as the Bengal Province in British colonial India. According to Vivek Bald (2013), one of the early streams of South Asian immigration was from the Bengal Province. These Muslim craftsmen started reaching the East Coast of the United States in the early 1900s to sell small items produced by traditional artisans and craftsmen. They brought embroidered silk — particularly the Chikan embroidery work of Bengal — and “exotic” goods, including rugs, perfumes, and a range of other items.

In fact, these peddlers followed the paths and interconnections developed by the British Empire for colonial trade and administration. By the early 1900s, a small number of these peddlers were traveling extensively throughout the United States, and they routinely moved through places such as New Jersey, Atlanta, and New Orleans to cater to a pronounced appetite for anything Indian or Oriental. New Orleans’s Tremé neighborhood became home to some of these Bengali Muslim peddlers who settled there and started families (Bald 2013). Multiple cases were recorded of Bengali Muslim men settling down in New Orleans and marrying African American or Creole of color women in a predominantly minority neighborhood.

Another stream of migration in the early twentieth century was South Asian seamen — primarily Bengali Muslims — who jumped British ships docked at the harbors of U.S. cities. Hundreds of South Asian maritime workers, who worked in very difficult conditions on British ships, disappeared into cities such as New York and Baltimore. A loose clandestine network of South Asian workers came into existence that helped each other escape ships and find work in nearby areas. They aspired to better working conditions and wages while navigating immigration hurdles.

“Despite very restrictive social and political conditions shaped by racist social and institutional orders, a group of South Asian immigrants organized one of the most significant transnational political interventions of the early twentieth century.”

Historical evidence suggests that this was a largely transient population that cycled through factory work and often went back to maritime work and made their way back to India. However, some decided to settle down in the United States and found spaces in working-class neighborhoods primarily inhabited by African Americans and other people of color in New York, Baltimore, and Detroit. They married African American, Puerto Rican, and West Indian women and created biracial families in neighborhoods such as Harlem in New York City. These remarkable stories about Muslim peddlers and maritime workers defy expectations and assumptions about the linear and insulated historical trajectory of South Asian migration to the United States, as they negotiated the race and class boundaries in that period by developing strong linkages with African American and other communities of color in New York City, New Orleans, and other urban areas (Bald 2013). The early history of South Asian immigration also points to the emergence of distinct religious groups that established some of the early Gurdwaras for Sikhs, temples for Hindus, and mosques for Muslims in the United States.

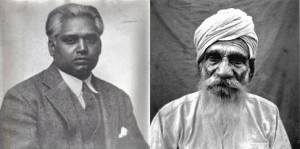

Despite very restrictive social and political conditions shaped by racist social and institutional orders, a group of South Asian immigrants organized one of the most significant transnational political interventions of the early twentieth century. Different groups and ideological trends within the Indian immigrant community came together, as Maia Ramnath (2011) narrates in her book Haj to Utopia, to form the Pacific Coast Hindi Association (PCHA) in October–November of 1913 in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. The group was formed with the mission to advance the struggle for India’s independence from British colonial occupation. Sohan Singh Bakhna, a Sikh laborer who initially worked in a timber mill, and Tarak Nath Das, a Bengali student, intellectual, and political activist, were the founders of PCHA and coordinated the branches of the organization throughout the Sikh farming community on the West Coast. They recruited Har Dayal, by then a well-known Indian political activist who worked with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in San Francisco, to edit the group’s publication, called Ghadar, and run its headquarters, the Yugantar Ashram, in San Francisco. Within a few months of its formation, the group’s membership had swelled to five thousand, with seventy-two North American branches, including those in Berkeley, Portland, Astoria, St. John, Sacramento, and Stockton. It was a unique attempt to bring Punjabi laborers and Indian student intellectuals together for a cause that was dear to both groups, and they not only reached out to South Asians across North America but also created networks among Indians serving in the British Army across the globe as well as Irish and Mexican nationalist groups (Ramnath 2011).

Even as the Ghadar Party’s reach expanded in the United States as well as transnationally, the legal status of Indian immigrants in the United States remained uncertain after the 1917 Asiatic Barred Zone Act that prohibited the entry of immigrants from Asia and Pacific Islands (Takaki 1998).

* * *

Excerpt appears here by permission of the University of Minnesota Press from “Introduction: Situating Desis in U.S. Ethnoracial Politics” from Desis Divided: The Political Lives of South Asian Americans by Sangay K. Mishra. Copyright 2016 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. www.upress.umn.edu.

In this interview the author speaks with Sonali Kolhatkar about the identities, immigration history, perceptions and political mobilization of South Asian Americans:

Sangay K. Mishra is assistant professor of political science at Drew University in Madison New Jersey, specializing in immigrant political incorporation, global immigration, and racial and ethnic politics. He is currently the co-chair of Asian and Pacific American Caucus of the American Political Science Association and a member of Committee on the Status of Asian Pacific Americans of the Western Political Science Association.