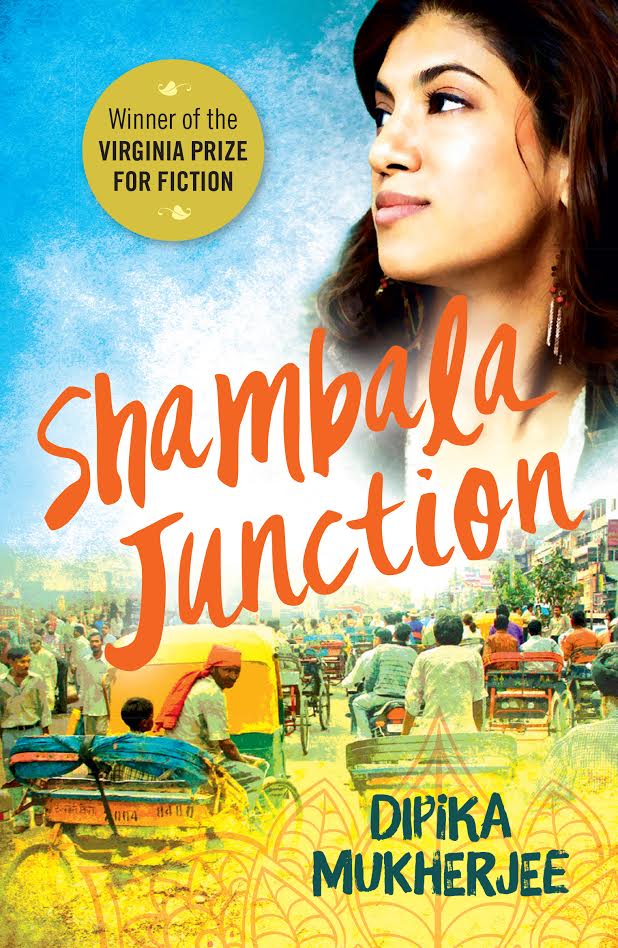

Dipika Mukherjee’s second novel Shambala Junction (Aurora Metro) is being released in the U.S. and worldwide on April 11. The novel deals with the corruption within international adoptions, and it won the 2016 U.K. Virginia Prize for Fiction, dedicated to women writing fiction in English around the world.

Dipika Mukherjee’s second novel Shambala Junction (Aurora Metro) is being released in the U.S. and worldwide on April 11. The novel deals with the corruption within international adoptions, and it won the 2016 U.K. Virginia Prize for Fiction, dedicated to women writing fiction in English around the world.

In Shambala Junction, Iris is visiting India from the U.S. for the first time with her fiancé, and not enjoying the experience. When she steps down off the train for a bottle of water at Shambala Junction, little does she know that her life is about to undergo a radical change. Stranded at Shambala, she becomes caught up in the drama of stall-holder Aman’s battle to recover his lost child. Along the way, she finds real friendship, learns what counts and grows to love India, in all its vivacity and charm. Read an excerpt from the novel below, shared with permission.

* * *

Chapter 1

Iris Sen was used to getting what she wanted. And she wanted this journey. Danesh, her fiancé, had tried to talk her into taking one of the fancy internal airlines to Delhi, but she had been adamant, seduced by the childhood stories about her father’s train journeys as a medical student through the hinterlands of India. Flying around India was not enough for this American daughter returning to a homeland after ten years; she insisted on a train, not like the Orient Express but something more, like, you know, real?

“What’s the point of being in India if we only see the inside of a plane?” she complained to Dan.

“You will not enjoy an Indian train.”

“I want to see the real India. Meet some real people.”

“You’ll have plenty of that. Sweaty, dirty, smelly people, surrounding you for hours. Not fun.”

“I’m tougher than you think I am, Dan.”

“You’ve never been on a bus in your life and you want to do a long-distance train?”

What she didn’t say was that Snapchat this past week had been filled with pictures of that emo Rachel LePage backpacking through Europe, knocking at unfamiliar doors that said Zimmer Frei! to spend the night… all that adventure on a Eurail pass. How much more awesome, more photogenic, would an Indian train ride be?

“You’ve never been on a bus in your life and you want to do a long-distance train?”

She had grown up with stories of camaraderie on an overnight train, and imagined selfies with fellow-travelers, the homemade food in gleaming tiffin carriers and fizzy drinks at every stop. She saw herself slightly disheveled, grubby but photogenic in a setting more colorful than Europe and seething with life.

“Come on Dan,” she cajoled, “if we wanted safe we should have stayed in Ohio! Don’t be such a wuss!”

So Danesh caved in (as he usually did), lured by the novelty and Iris’ enthusiasm. It was going to be a 24-hour train ride from Kolkata to Delhi, 26 tops, if the train was delayed. How bad could it get?

Iris woke up at 2:35 in the morning to the train shuddering to a stop, then (as she understood very little Hindi and spoke the language not at all), a foghorn of sound. The train compartment was still dimly lit, the sagging curtains partially drawn around the compartment designed for six sleeping passengers. Less than twelve hours had passed since they had boarded this train in Kolkata, but this journey felt much longer. She wasn’t ready to admit that she was regretting not taking the plane.

A young man sauntered by, lit by the faint neon light in the corridor, and tossed a paper packet on her feet. Iris had reached out gingerly to read the message smeared in blue ink on the dirty paper: I only saw your feet… they are very beautiful. Don’t let them touch the ground or they will get soiled.

Chee! Iris sat up. The packet had once held something mildly oily, and she held up the scrawl with her fingertips and wrinkled her nose; God only knows what germs were in the writer’s drool. She hurriedly dropped the packet.

“Her own memories (from a trip to India at the age of twelve) had the unreal quality of old sepia photographs.”

This trip to India felt like being thrown into the back of a garbage truck — every surface was coated with something unclean — even the disinfecting wipes here felt contaminated. She had never enjoyed trekking in the great outdoors of America because of the bugs, and here she was, on a train in India, where no place was safe from disgusting diseases and scampering cockroaches. None of the Indian stories she had heard in Ohio had prepared her for this reality; clearly, the community had collectively misimagined their nostalgia for mother India. Her own memories (from a trip to India at the age of twelve) had the unreal quality of old sepia photographs.

By the faded lettering on the sign she could make out they had stopped at Shambala Junction. Peering at her watch again she saw it was 2:39 in the morning and she craned her neck to see Danesh sleeping, his head angled to the front of the topmost sleeper so that their valuables (his backpack, her purse) could be wedged behind his 6 ft 2 frame, far away from casually thieving fingers. Through the windows of the sleeper compartment, she could see a group of Japanese tourists disembarking. The Indian guide was very solicitous with the geriatric tourists while gesturing imperiously at the coolies flocked around this large group. A young Japanese woman stood slightly apart from the group, finishing an entire bottle of mineral water in one long gulp.

Iris felt thirst tightening the length of her throat. She reached for her bottle of mineral water in the dark and shook it to confirm it was empty; she had finished it before she fell asleep. She could see the man selling tall Bisleri mineral water bottles not too far away on the platform.

Next to the water vendor was a doll-seller, his upper body covered in a threadbare singlet with two dark semicircles around the armpits. He had an array of colorful wooden dolls spread out in front of him on a pushcart: there were dolls with turbans and flared coats playing flutes and dholaks; there were men riding horses with colorful stirrups and dazzling sword-sheaths; there were dancers dancing with the left leg slightly on tiptoe, caught in mid-swirl in the disarray of flouncing skirts.

Iris was enchanted. She had once owned a dancing doll just like that one, a beloved painted wooden thing with a crack in the veiled head, a gift from some unremembered relative in her childhood. She wanted some water as much as she wanted to hop off and buy a doll — it would be so cool to find the unblemished twin of the one in her closet in Ohio.

The air outside was refreshingly cool; the doors on both sides of the carriage were open. Immediately, the smell of hot puris fluffing into golden balls assaulted her nose. Even at this time of night the puri wallah on the platform had a small line of buyers, and he deftly spooned a liquidy potato curry into a leaf bowl as his helper covered it with two piping hot puris. The waiting buyer grasped the package and juggled it nimbly as the heat scorched his hands. The train conductor was filling up a red water bottle from a tap. The Japanese tourists were finally moving, after loading all their suitcases and backpacks into a two-wheeled luggage-barrow propelled by four lean coolies.

“Immediately, the smell of hot puris fluffing into golden balls assaulted her nose.”

The train felt solidly still as Iris walked towards the bottles of water. For all she knew, they could be here for another half an hour. The journey so far had been erratic, with stops and starts in the most unlikely places. She looked back nervously at the large Victorian station clock which pointed to 2:41, but the train was totally immobile, as if it too were asleep. As she headed for the drinks stall, she checked for the money pouch attached to her belt and took out a single frayed note.

The cool water trickled deliciously down her throat. She had gulped the entire contents down and was tossing the bottle into a bin when “Chai garam,” a nasal voice sounded near her waist and a hand simultaneously thrust a small bowl of hot tea in her direction. The tea splashed on her hand and made it feel instantly gummy. She suppressed the instinct to reach for her disinfecting wipes and scrabbled in her money-belt for some change, unwilling to deny the little boy with the dirty towel around his neck his due even though she disliked milky chai. The boy took the money as he stared at her, eyes assessing her clothes, breasts and hair, then someone shouted “Chaiwallah!” and he turned swiftly, the aluminium kettle in his hand dribbling a line of tea on the platform towards his new customer.

Tea in hand, Iris wandered towards the doll-seller, hesitantly looking back again after a few steps. She walked a little further, sipping the hot tea slowly, blowing her breath into the little opening. As she gulped down the last dregs of liquid, she saw the boy pocketing change from another customer further down and she ran after him along the long platform, to return the little clay bowl.

“Here,” she said. “Thank you. Good chai. Ach-cha.”

The boy looked at her breasts, outlined through her tight T-shirt, and grinned, ignoring the extended bowl. “Here,” Iris tried again. “Your cup.”

The boy looked puzzled then, seeing what was in her hand, took her cup, lingering on her fingers a little longer than was necessary, and smashed it against the railway tracks.

“What the…?” Iris looked at the shattered shards in dismay. “Why did you…?”

Then she noticed that many such little clay bowls lay broken along the rails. Eco-friendly, she realised, terracotta to mud, and wondered how to ask the chaiwallah for a souvenir cup to show off back home in Ohio.

She followed the boy, who had walked further down the platform and was pouring fresh tea into his aluminium teapot from a frothing saucepan. Two men lounging by a pillar chortled “Hello Dear! Hello Darling!” in her direction, but she walked resolutely on, and tapped the tea boy’s shoulder gently.

That was when she sensed a slight rumble, and, heard the deep sigh of air expelled from a lumbering engine. As she whirled around, she could see the train starting to move away. She saw the other tea drinker dash his half drunk cup against the rails and another one further up the line do the same, and they both swiftly hopped on to the train. Surely the whistle should have blown or something?

“That was when she sensed a slight rumble, and, heard the deep sigh of air expelled from a lumbering engine.”

Iris’ feet remained glued to the concrete of the filthy platform as panic coursed through her blood. The tea-boy poked her waist sharply.

“Bhago!” he urged, waving both his hands towards the train as if shooing her there.

Her feet started to move but although she began to jog along the platform she just couldn’t run fast enough.

She slid on something slimy and careered into the group of Japanese tourists who stood blocking her dash for the train. Her ankle exploded in pain.

“Bhago!” the tea-boy shouted, keeping pace with her, a lot more urgently this time, and his words were echoed by the people around her, all gesticulating for her to move more quickly and shouting encouragement in Hindi. As she continued to run along the platform, the pain in her ankle grew more acute, her chest was exploding and tears began to blur her vision of the departing train.

She didn’t see the raised edge of the luggage trolley. Instead, her right toe stubbed on something hard and then it was a blur as she fell into the doll-seller’s stand her leg flailing in the air while her hands reached for the ground. There was a crash as the array of wooden dolls tumbled to the ground and smashed.

Iris raised her head very, very slowly to survey the damage. There were beheaded dolls and limbless animals everywhere. The doll-seller was shouting obscenities she barely understood.

Iris felt herself trembling. Anyone could see that she hadn’t deliberately destroyed the man’s stand. A couple of bystanders kicked at the mangled toy-limbs, while other vendors surrounded the doll-seller, sympathising with one of their own. She closed her eyes to blot out the sight and the sound and the smells, but it didn’t help. It was all too awful. And where was Danesh when she needed him?

* * *

Dipika Mukherjee has published three works of fiction; her second novel, Shambala Junction, will be released in the U.S. in April 2017 (it won the Virginia Prize for Fiction in the UK in November 2016). Her debut novel was longlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize and republished as Ode to Broken Things and is available in bookstores as well as on Audible. Her short story collection is Rules of Desire.